- Contents

- Editors' Note

- Acknowledgments

- Dickinson's Transplantation of Citizenship in the Earth: An Un-Silencing by Beth Staley

- “We send the Wave to find the Wave”: Dickinson’s Wave-Particle Duality by Mary Loeffelholz

- “Then quiver down, with tufts of Tune –”: Dickinson’s Palpable Soundscapes by Joan Wry

- “Buccaneers of Buzz”: Dickinson’s Humanimal Poetics by Alison Fraser

- Going to Sea in Emily Dickinson’s Poetry: Decentered Humanism and Poetic Ecology by Brian Yothers

- Coda: Natural Messages and Aesthetic Pleasure in Emily Dickinson’s Nature Writing by Grace Mei-shu Chen

“Then quiver down, with tufts of Tune –”: Dickinson’s Palpable Soundscapes by Joan Wry

Current theories of soundscape ecology suggest that the sound recordings of landscapes—the aural record of all biological and geological sounds in a natural area—may one day become “tomorrow’s acoustic fossils, possibly preserving the only evidence we have of ecosystems that may vanish in the future.”[1] Another recent study laments “the sparseness of literature on the auditory aspects of landscapes,” a reality that reflects the “hegemony of vision,” but perhaps more significantly points to what one theorist calls our culture’s tone-deaf “nature deficit disorder,” a dissonance that is “only increasing as we replace natural sounds with the din made by humans.”[2] The National Science Foundation is currently funding projects to use data from acoustic recordings to design soundtopes—detailed, three-dimensional maps of sounds “plotted across the landscape”—constructs that may all too soon become acoustic fossils in our rapidly changing climate and world.[3]

My essay proposes that a number of Emily Dickinson’s poems offer their own form of language-based acoustic fossils in which nineteenth-century landscapes—both literal and figurative—timelessly vibrate with sound; their “tunes” are both heard and felt. In these poems, Dickinson’s emphasis on palpable sound is supported by the physics of sound and the research of modern soundscape theorists: because sound waves penetrate nearly all animate and inanimate matter, we can expect that each wave cycle of sound (or “frequency”) produces a distinct vibrating response in the medium through which it passes.[4] In Dickinson’s poems, these vibrating mediums are often trees and grass blown by the wind, the throats and wings of birds in song and flight, the reverberating human ear and mind—as well as human constructs such as bells, factories, trains, anvils, and forges.

Moreover, Dickinson’s lyric soundtopes can also be seen as three-dimensional maps of acoustics plotted in language; they give heard and felt signifiers for the ways she perceived her varied landscapes. Dickinson of course offers “three dimensional” length, breadth, and depth of meanings in these poems, but her vast range of images and tactile sounds also reflects her understanding of this spatial concept as a longstanding geometric model of the physical universe.[5] Perhaps more significantly, Dickinson’s palpable soundscapes give insight into the ways she understood what it meant to be a poet of the highest order—one who transmits and translates the forms of music that most of us would not be able to hear on our own . . . those “tufts of Tune –,” as she says in one of her most provocative sound-based poems (Fr. 334B), “Permitted Gods, and me –.”

Although far less lyrical in their approach, today’s designers of soundtope maps are guided by some of the same principles of analytic geometry and physics in their research, and their publications reflect surprisingly consistent three-fold approaches to defining terms and explaining context. Tripartite structures abound in soundscape ecology; not only are soundtope maps three-dimensional acoustic plottings, but the sonic sources that form soundscapes are commonly understood in three distinct categories.[6] “Geophonies” are the source of sounds produced by nonbiological natural agents such as winds, sea waves, rain, and thunder; “biophonies” are comprised of biological sounds: animal calls such as birdsong, as well as the varied sounds produced by amphibians and insects; and “anthrophonies” are the result of all the sounds produced by human design and technology, the noise of engines and machinery, bells and chimes, tools and factories, and more recently, cell phones and other smart devices. Soundscape ecologist Almo Farina determined that the spatial overlap of these three sonic sources creates a pattern which has “zones of contact”; he refers to these soundtope intersects as “tension zone[s] of acoustic uncertainty.”[7]

R. Murray Schaffer, an early soundscape theorist and a renowned composer of music, offered his own tripartite designation for the components of a soundscape, naming keynotes, sound signals, and soundmarks as categories of distinction for background sounds, foreground sounds, and sounds that are analogous to landmarks—those defining sounds with symbolic and even archetypal meanings in a particular location.[8] And finally, theorists including Almo Farina, Bryan Pijanowski, and Bernie Krause have collectively agreed that landscapes and their corresponding soundscapes can be conceptualized in “three main currents of thought”: first from a geographic perspective, by addressing the sight and sound descriptions of land forms and bodies of water; second from an ecological perspective, by taking into account the “ecological valence of the landscape as a spatial arrangement of ecosystems,” and finally, from a cognitive perspective, one that considers the landscape and corresponding soundscape as “cognitive conceptions that are first created in the mind of the observer.”[9] And while Dickinson’s sound-based poems aren’t characterized by consistent tripartite structures, there are interesting connections between her lyrical ecologies and some of the new research in soundscape ecology. For example, it is certainly possible to consider many of her lyric landscapes (to borrow Farina’s phrasing above), as “cognitive conceptions first created in the mind of the observer.”[10] A number of these poems also feature zones of tension, contact, and ambiguity when different sonic sources overlap and intersect. And in unique and intriguing ways, Dickinson’s own select diction of sound defines the features of her palpable soundscapes in multidimensional contexts, and from perspectives that are not altogether inconsistent with modern soundscape theories.

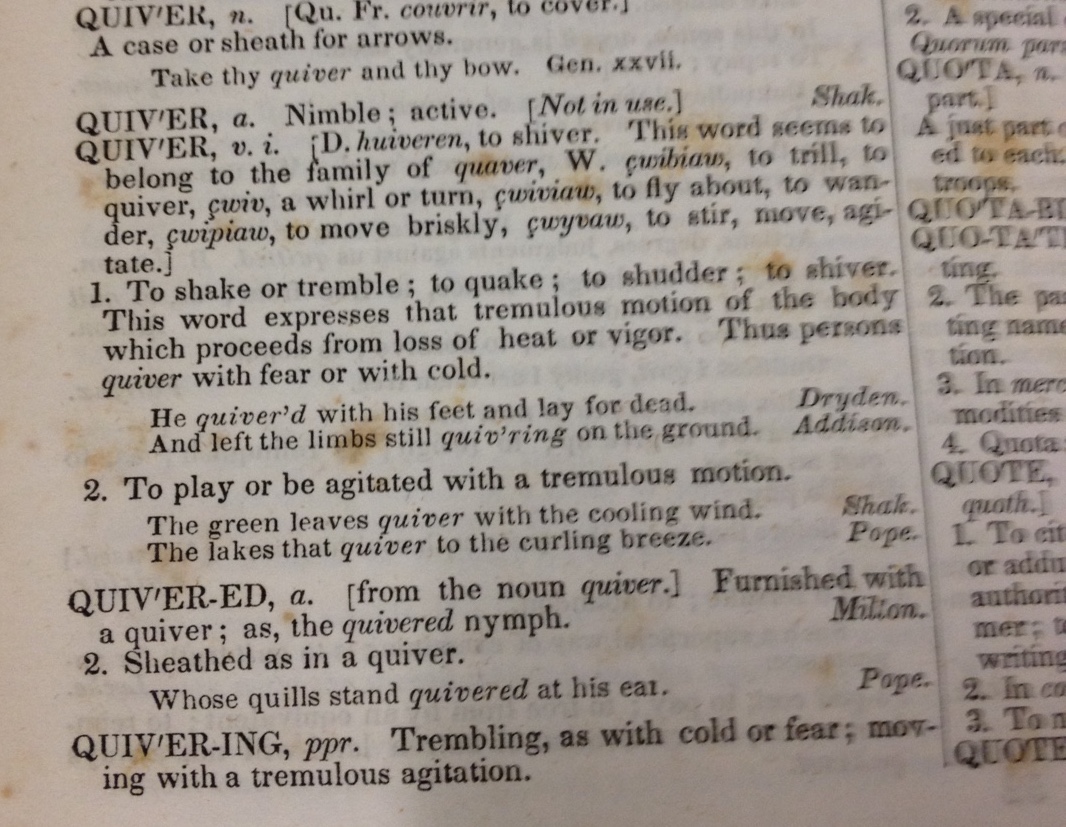

Consider the word “quiver,” a term Dickinson uses with its variant forms for both inanimate wind and animate birds in a number of her poems. The 1844 Noah Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language—Dickinson’s “Lexicon” and her self-described “only companion” (JL 261)—defines quiver as, “to play or be agitated with a tremulous motion.” Dickinson seems to choose the interpretive verb “to play” over its apparent contradiction “to be agitated” in select poems in which modulations in music or distinctive changes in key may provide a context.[11]

Fig. 1. Entries for “Quiver” from Noah Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language (1844).

In the soundscape of poem Fr. 397[A], a bird “trilled, and quivered, and shook his throat” as a funerary train of mourners pass through a burial gate (lines 1-3). The sound produced by this vibration then resonates in waves through the medium of air, “Till all the churchyard rang” with the sound of birdsong, a sonorous moment that prompts the bird to “adjust his little notes” to a new modulation and “sing again” (lines 4-6). The biophony of birdsong dominates over the likely presence of unnamed geophonies and anthrophonies in this poem; it “br[eaks] forth” (line 2) and then vibrates through other mediums—through the ears of the mourners passing through the burial gate, and through the churchyard itself, which rings in resonant response to the bird’s trilling and quivering.

“Resonance” is another term in Dickinson’s select diction of sound; her 1844 Webster’s defines the word as, “reverberated sound or sounds” within a semi-enclosed space—and in poem Fr. 1489B (MS AC 816), the rapid vibrations of a hummingbird’s wings make sound travel and then resonate with brilliant color: the “Resonance of Emerald” and “Rush of Cochineal” in lines 3 and 4. Through a seeming mixed metaphor, fleeting evanescence and dazzling aural movement result in an optical illusion, “a revolving Wheel” (line 2) of rapidly vibrating wings that conjoins sight and sound, landscape and soundscape, in the small and semi-enclosed space of the poem:

.jpg)

(1).jpg)

Fig. 2. AC 816 (in part), “A Route of / Evanescence,” inscribed in a letter to Helen Hunt Jackson, c. 1879.

Courtesy of Amherst College Archives & Special Collections.

Significantly, resonance can also occur between different types of vibrations—including those of color and sound—simply because resonance is a possible response when even widely disparate vibrations are within range of one another. In all seven (six extant) manuscript versions of poem Fr. 1489 (Forbes Library, AC 816, AC 32, BPL 102, AC 766, AC 833, AC Tr45 / AC Tr49), Dickinson seemed to understand the phenomenon of resonant potential between color and sound not only with vivid poetic intensity, but with “sound” and proven science.[12]

And yet Dickinson focuses most of her palpable sound intensity on the geophony of wind—which quivers, speaks, rocks, taps, calls, and loudly threatens in nearly a dozen poems. In most instances, the wind is emphatically anthropomorphized and definitively gendered, a human male who is alternately weak and worn or mighty and forceful. In poem Fr. 621A, the “Push” of numerous vibrating Humming Birds is used in resonant comparison to the palpable “Speech” of wind that “taps” on a door like a “tired, timid Man” (lines 10-11; 18-19). In Fr. 796 and Fr. 1618, the wind is a male agent of invisible energy inspiring fear and awe in powerful storms; in Fr. 796C a Jove-like wind rocks the grass with “low” and “threatening Tunes,” then throws palpable reverberations of “Menace” at both earth and sky (lines 1-4). The forceful “Bugle”-like Wind of Fr. 1618A “quiver[s] through the Grass” in a chaotic soundtope that includes the wild vibrations of a steeple “Bell” and the palpable breath of animate “panting Trees” (lines 1-2; 13; 9). In Fr. 1441B (MS AC 224), a variant perspective on felt sound is found in the affect of feelings and emotions. In a clever and speculative inversion, instead of “feeling” the wind, the speaker of the poem wonders about the way the male-gendered wind “feels” in response to isolation and detachment: “How lonesome the Wind must feel Nights – / When People have put out the Lights / And everything that has an Inn / Closes the shutter and goes in – ” (lines 1-4).

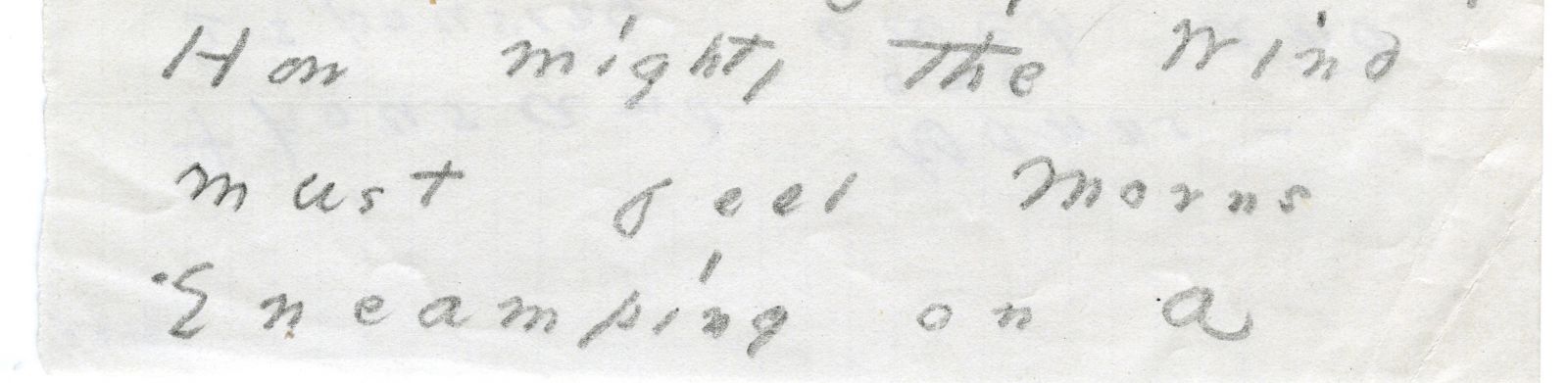

Notably, other compensatory attributes (and the empowering human feelings they generate) counterbalance these forlorn opening lines. The wind must also feel “pompous,” the speaker speculates, when ceremoniously “Stepping to incorporeal Tunes” in line 6; it has impressive range in “Correcting errors of the sky / And clarifying scenery” in the broad sweep of lines 7 and 8. And it must feel undeniably “mighty,” the speaker concludes, when it presides with military (and even godlike) omnipotence in the poem’s closing lines: “How mighty the Wind must feel Morns / Encamping on a thousand Dawns – / Espousing each and spurning all / Then soaring to his Temple Tall – ” (lines 9-12):

.jpg)

Fig. 3. AC 224, “How lonesome the / Wind must feel Nights –”, about 1877 (detail).

Courtesy of Amherst College Library Archives & Special Collections.

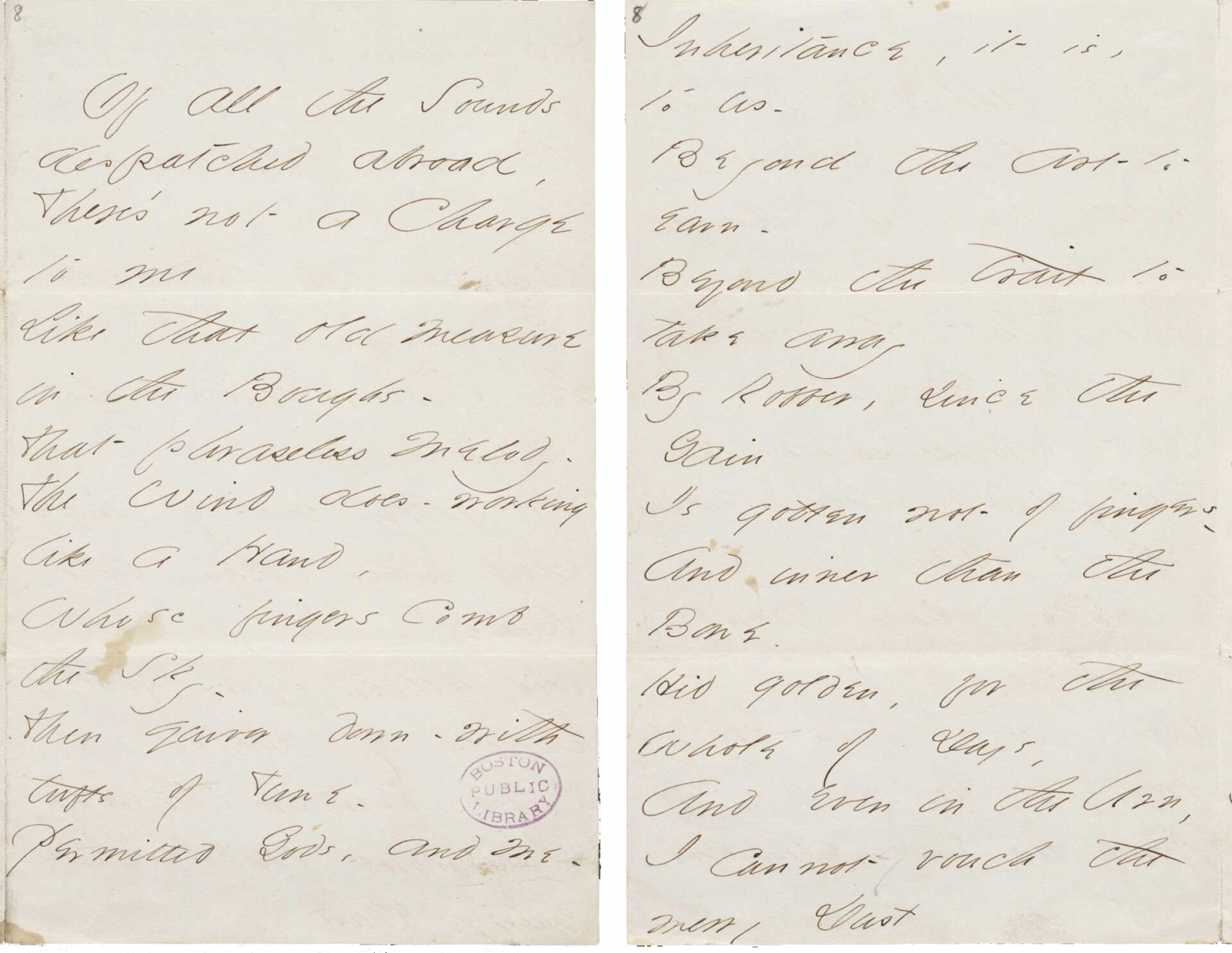

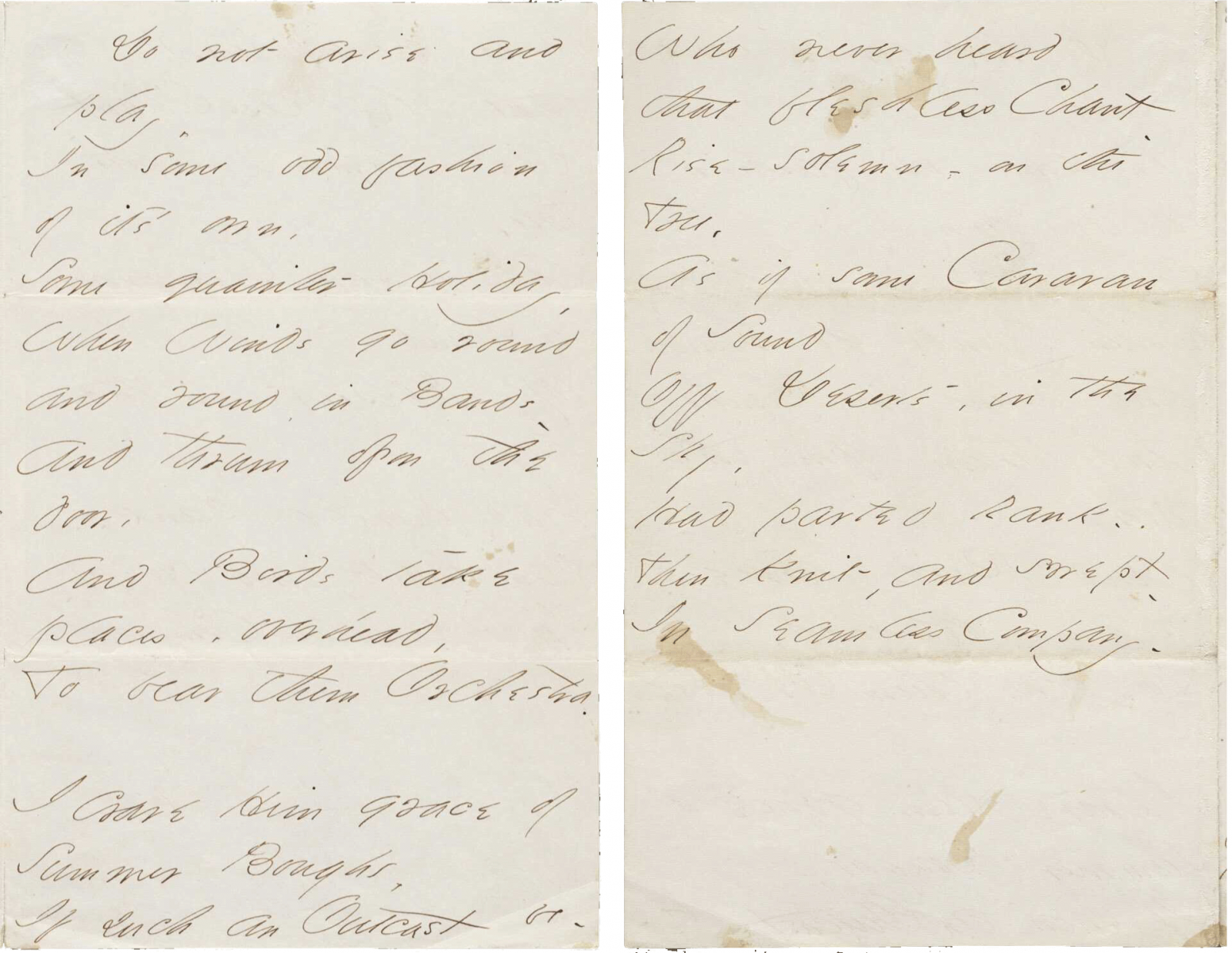

But wind is not always definitively gendered, nor is it always recognizably anthropomorphized, even when human body parts are used as descriptors. This is the case, in fact, in the poem that gives this essay its title and that offers one of the richest and most complex soundscapes in Dickinson’s work, “Of all the Sounds despatched abroad” (Fr. 334B/MS BPL 6).

Fig. 4. BPL Higg 6, “Of all the Sounds / despatched abroad,” c. 1862, enclosed in a letter to T. W. Higginson.

Courtesy of the Boston Public Library.

Here, the use of a gendered reference in the first line of the last stanza is ambiguous; the “Him” that the speaker “crave[s]” in line 25 could be the wind, but it could also be an intentional homophone for “hymn” as a song of prayer, or a different reference altogether—perhaps even the “Outcast” of line 26: “I crave Him Grace of Summer Boughs, / If such an Outcast be – / Who never heard that fleshless Chant –/ Rise – solemn – on the Tree” (lines 25-28).

The language of music abounds in the soundtope of Fr. 334B: the words “Melody,” “measure,” “Tune,” “play,” “thrum,” “Chant,” and “Orchestra” all suggest the parts and processes of a concert or a grand performance. The significance of this interlude is established at the onset: in the first stanza, the “phraseless Melody –” of the Wind has “fingers” that first “Comb the Sky –” and then “quiver down” the landscape, their audible touch (“working like a Hand”) creating “tufts of Tune –”perceived only by poets and deities in lines 4-8. “Of all the Sounds despatched abroad” (line 1) in Dickinson’s soundtope, only the wind transcends the full “measure” (line 3) of the landscape, and its ability to go “round and round in Bands –” (line 21) as the poem widens hints at Circumference—Dickinson’s self-proclaimed “Business” or calling (JL 268). In the second line of the poem the speaker is “Charge[ed]” by the power of the wind as if it were celestial energy; she also is designated as a lyric prophet by the wind—“Charg[ed]” to proclaim an “Inheritance” that is beyond the “Art to earn –” (lines 9, 10). In this sense, the anthropomorphized fingers of the Wind are female—the poet’s own “working [of] a Hand” that communicates privileged insights by transcribing sonorous lines of poetry. Birds are positioned in an orchestrated chorus in the second stanza, where they “take [their] places, overhead” (line 23), and even the ashes of the dead may well “arise and play” (line 18) in resonant response: “I cannot vouch the merry Dust / Do not arise and play, / In some odd fashion of it’s own, / Some quainter Holiday” (lines 17-20).

The “fleshless Chant” that “Rise[s] – solemn – on the Tree” in lines 27 and 28 then echoes the image of the dead rising from their urns, and the poem’s widening reverberations are continued in a pattern of heard and felt vibrations: “When Winds go round and round in Bands – / And thrum opon the door” (lines 21-22). In the final lines, an endless wave of “Seamless” auditory energy then appears to continue beyond the expanse of the poem into realms unheard and unknown:

As if some Caravan of Sound

Off Deserts, in the Sky,

Had parted Rank –

Then knit, and swept –

In Seamless Company – (lines 29-33)

Often in lyric poetry, birdsong is the poet’s song, but Wind (or Spiritus) is more significantly the poet’s inspiration. Both tropes are resounding aspects of Dickinson’s sonic ecologies—embodying the heard and felt music of her lyric landscapes, but in Fr. 334B (and others like it), Dickinson reveals that she hears those higher frequencies of sound the rest of us fail to perceive. Her poet’s ear and mind resonate with the “Gain” of the rarified language of Nature that is “permitted” only to “Gods” and their prophets (lines 12, 8), and in the process she may well be hearing the very Music of the Spheres. Regardless, music is the sound Dickinson hears most essentially—especially the “phraseless Melod[ies]” of Fr. 334B (line 4) that may even be a form of transcendent or celestial music.

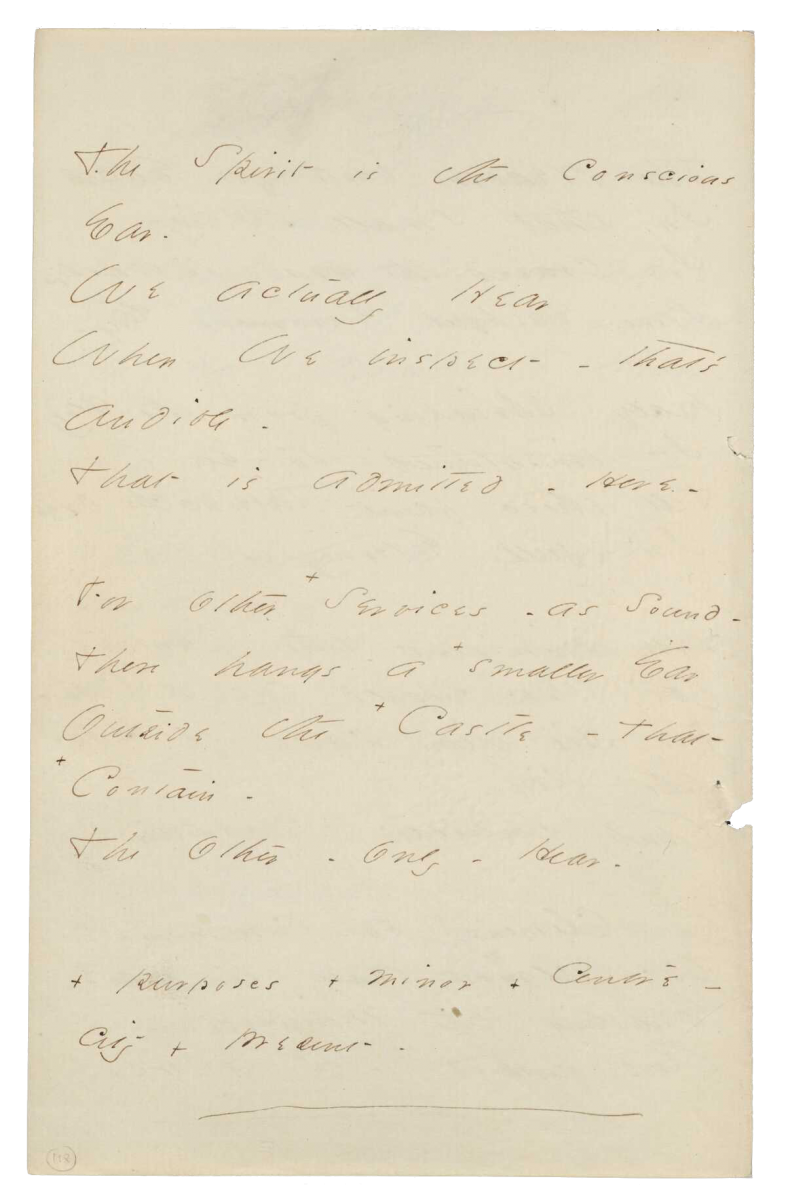

“The Spirit is the Conscious Ear –” she affirms in Fr. 718A (MS H 118), the one that matters in the “Here” and now of consciousness. Those other services and sounds are the stuff of less poetic vibrations in an anatomical ear that hangs “outside” the more privileged “Castle” that contains the mind: “For other Services – as Sound – / There hangs a smaller Ear / Outside the Castle – that Contain – / The other – only – Hear –” (lines 4-7).

Fig. 5. H 118, “The Spirit is the Conscious / Ear –,” c. about the second half of 1863.

Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

With characteristic three-fold emphasis, R. Murray Shaffer describes the soundscape of the world as “a huge musical composition [that] unfold[s] around us ceaselessly. We are simultaneously its audience, its performers, and its composers . . . . so which sounds do we want to preserve, encourage, and multiply?”[13] Dickinson’s sonic ecologies invite us in these roles to ponder the same questions. “Hers is an audacious poetics that pushes language to the very edge of meaning and, at times, beyond,” Joanne Feit Diehl affirms in describing the way that Dickinson “invest[s] the world with her consciousness.[14] And in poems invested with an astonishing intersect of palpable sounds, Dickinson helps us all to better hear the music of her lyric landscapes, as well as the music beyond.

Joan Wry, Saint Michael’s College

Notes

[1] Dybas, Cheryl. “Studying Nature’s Rhythms: Soundscape Ecologists Spawn New Field.” National Science Foundation Online, National Science Foundation, 6 Feb. 2012, www.nsf.gov/discoveries/disc_summ.jsp?cntn_id=123046

[2] Dybas, par. 31. Dybas quotes soundscape theorist Bryan Pijanowski on the “increasing din made by humans” and acknowledges the ongoing support of the National Science Foundation to support the research of “Pijanowski and colleagues” (par. 11).

[3] Dybas, par. 26.

[4] Sound waves are an actual physical motion of molecules that can be measured in cycles per second, and each medium through which sound energy passes will respond with a distinct pattern of reciprocal vibrations. For example, low frequency vibrations (with fewer cycles per second), are so significant to the human body that they cause our organs to respond with a sympathetic, palpable vibration; not only do our eardrums vibrate back and forth in response to sound waves, but certain low frequency sounds cause our entire bodies to reciprocate with a vibratory movement that can be felt physically. These palpable sounds (the deep bass of organ music—Dickinson’s “Heft / Of Cathedral Tunes –” in Fr. 320A comes to mind), are both heard and felt. I am indebted to a conversation with Saint Michael’s College Physics Professor William Karstens for a general understanding of the transmission of sound waves through different mediums.

[5] Dickinson would have been introduced to the three coordinates of analytic, or Cartesian, geometry at the Amherst Academy; she also would have known of Euclidian three-dimensional space in her study of physics and mathematics.

[6] In 2009, Almo Farino and Bryan Pijanowski organized the first international Soundscape Ecology conference at which definitions and terms for this new field were agreed upon.

[7] Almo Farina, Soundscape Ecology: Principles, Patterns, Methods and Applications, Springer, 2013, p. 1.

[8] See pages 9-11 of Schafer’s The Soundscape (Knopf, 1994), for a more specific explanation of this variant tripartite designation for the components of a soundscape.

[9] Farina, 15.

[10] Farina, 15.

[11] While Dickinson’s lexicon was most likely Webster’s Dictionary, the “compiled” Lexicon, the online research option provided by Brigham Young University, interprets one version of Dickinson’s use of the verb “to quiver” in her poems as, “to vibrate; to produce sweetly modulated musical tones”—or to produce music that is played and perceived pleasurably.

[12] Color is an electromagnetic vibration that can resonate with the slower compressional waves of sound (see the website Biogeometry.org for a general explanation of this phenomenon). Correlations between color, sound, and frequency were known in the 19th century; Goethe had published his 1400-page treatise on the science of color in 1810, although it is unlikely that Dickinson read this material.

[13] Shaefer, 205.

[14] Joanne Feit Diehl, “The Ample Word: Immanence and Authority in Dickinson’s Poetry.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, vol. 14, no. 2, 2005, p. 9.

Works Cited

Diehl, Joanne Feit. “The Ample Word: Immanence and Authority in Dickinson’s Poetry.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, vol. 14, no. 2, 2005, pp. 1-11.

Dybas, Cheryl. “Studying Nature’s Rhythms: Soundscape Ecologists Spawn New Field.” National Science Foundation Online, National Science Foundation, 6 Feb. 2012, www.nsf.gov/discoveries/disc_summ.jsp?cntn_id=123046

Farina, Almo. Soundscape Ecology: Principles, Patterns, Methods and Applications. Springer, 2013.

Schafer, R. Murray. The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World. Knopf, 1994.

Image Credits

Fig. 1. Entries for “Quiver” from Noah Webster’s American Dictionary of the English Language (1844). Photograph taken by author from a copy of the dictionary owned by the Amherst College Library,. No digital surrogate available.

Fig. 2. AC 816 (in part), “A Route of / Evanescence,” inscribed in a letter to Helen Hunt Jackson, c. 1879. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives & Special Collections. For links to the source images, see:

https://acdc.amherst.edu/view/asc:17206 & https://acdc.amherst.edu/view/asc:17206/asc:17209

Fig. 3. AC 224, “How lonesome the / Wind must feel Nights –”, about 1877 (detail). Courtesy of Amherst College Library Archives & Special Collections. For links to the source images, see: https://acdc.amherst.edu/view/asc:5957 & https://acdc.amherst.edu/view/asc:5957/asc:5961

Fig. 4. BPL Higg 6, “Of all the Sounds / despatched abroad,” c. 1862, enclosed in a letter to T. W. Higginson. Courtesy of the Boston Public Library. For links to the source images, see:

http://www.edickinson.org/editions/1/image_sets/237972 & http://www.edickinson.org/editions/1/image_sets/237973 & http://www.edickinson.org/editions/1/image_sets/237974 & http://www.edickinson.org/editions/1/image_sets/237975

Fig. 5. H 118, “The Spirit is the Conscious / Ear –,” c. about the second half of 1863. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University. For a link to the source image, see: http://www.edickinson.org/editions/1/image_sets/236039