- Contents

- Editors' Note

- Acknowledgments

- Dickinson's Transplantation of Citizenship in the Earth: An Un-Silencing by Beth Staley

- “We send the Wave to find the Wave”: Dickinson’s Wave-Particle Duality by Mary Loeffelholz

- “Then quiver down, with tufts of Tune –”: Dickinson’s Palpable Soundscapes by Joan Wry

- “Buccaneers of Buzz”: Dickinson’s Humanimal Poetics by Alison Fraser

- Going to Sea in Emily Dickinson’s Poetry: Decentered Humanism and Poetic Ecology by Brian Yothers

- Coda: Natural Messages and Aesthetic Pleasure in Emily Dickinson’s Nature Writing by Grace Mei-shu Chen

Going to Sea in Emily Dickinson’s Poetry: Decentered Humanism and Poetic Ecology by Brian Yothers

Emily Dickinson seems an inland poet: after all, she lived the overwhelming majority of her life in Amherst, Massachusetts, far from any shore, and if we recall her writing about seas or oceans at all, we most likely recall lines like “Rowing in Eden – / Ah – the Sea! / Might I but moor – tonight – / In thee!” (Fr. 269A), where the sea seems as much like a material part of our everyday world as the Garden of Eden. And yet, Dickinson devoted many of her poems, 96 by my count, to images and themes directly associated with the sea, with drowning, with the tides, and with the confrontation between sailors and their environments.

Analyses of Dickinson’s treatment of the sea are patchy despite a few valuable discussions by Cristanne Miller, Francis V. Madigan, and Margaret H. Freeman. Cristanne Miller’s insightful Reading in Time (2012) emphasizes Dickinson’s treatment of the “turban’d seas” as an example of the cross-cultural dimensions in her poetry, an insight I seek to complement with a sense of how the sea also provides us with a Dickinson who decenters human subjectivity through her use of images of the tides, drowning, and the immensity of the sea. Most recently, Freeman offers an anatomy of Dickinson’s sea metaphors in “Nature’s Influence” (2013), but her metaphoric focus necessarily leaves aside the question of how the sea operates as something more than a metaphor for Dickinson. As Hester Blum has trenchantly argued, “the sea is not a metaphor” (670)—it cannot be contained by linguistic framing—and we can read Dickinson on the sea most usefully when we acknowledge that the sea’s materiality pushes against the boundaries of her language, even as her language pushes back. Dickinson’s seas might seem to be abstractions—at best, compelling metaphors, at worst, appeals to a part of human experience far removed from Dickinson’s own daily experiences in inland Amherst, and thus tending toward the shoals of cliché. And yet Dickinson manifests a remarkable ability to speak about the sea concretely and creatively.

*

Lost at Sea: Dickinson’s Late Poems of Drowning and the Limits of the Human

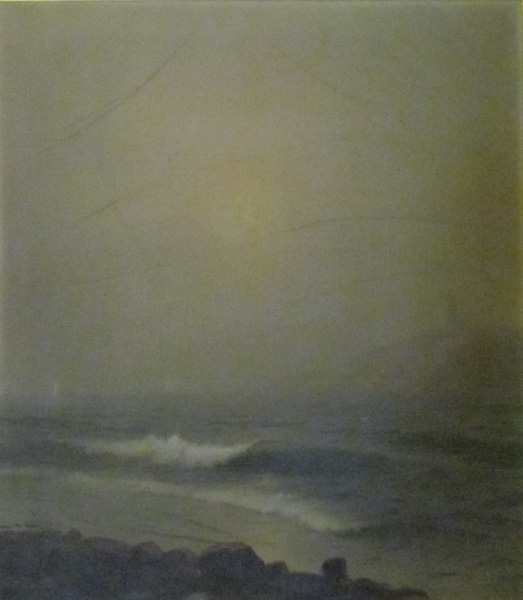

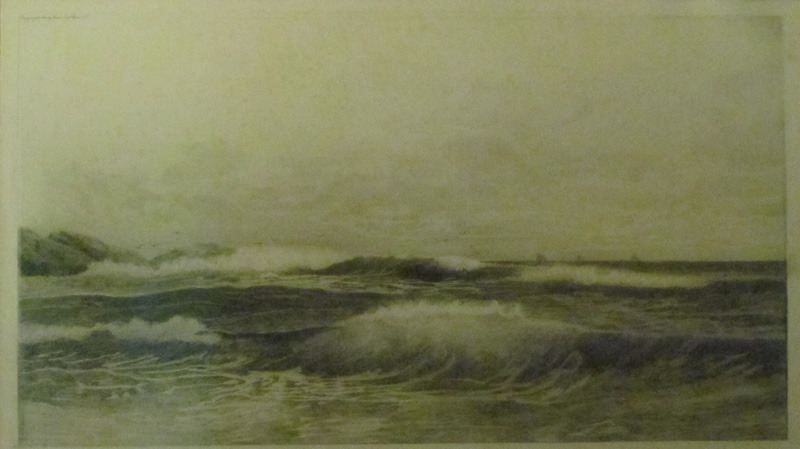

Fig. 1. Cook, R. Seascape with Fog.

Oil on canvas. Frame: 36 1/2 in x 33 1/2 in x 4 1/2 in; 92.7 cm x 85.1 cm x 11.4 cm; Sight: 23 1/2 in x 20 1/2 in; 59.7 cm x 52.1 cm. AC EDM 2003.216.

Collection of the Emily Dickinson Museum, Transfer from Martha Dickinson Bianchi Trust.

We see Dickinson’s emphasis on the materiality of the sea—the way in which she understands it as more than a metaphor—most clearly in her late poems. Near the end of her life, Dickinson began writing poems that referred to the sea, and particularly to the experience or threat of drowning, with increasing frequency. A handful of powerful examples can illustrate this trend, and can frame a brief taxonomy of the ways in which she used the sea across her career. In these poems, Dickinson does not so much discern anthropocentric lessons from nature but rather creates new forms that account for a non-anthropocentric universe. Even as Dickinson decenters human consciousness in her sea poems, there is also a powerfully humanistic dimension to the poems balancing the aspects that suggest post-humanism to twenty-first century readers. Humans in these poems (and, frequently, birds as well) are enmeshed in a struggle to respond creatively to a context that restricts their agency. In the period running from 1877 to 1880, Dickinson considers the sea and drowning in Fr. 1446A, Fr. 1456A, Fr. 1469A, Fr. 1503A, B, and Fr. 1542[B]. The sense of threat to human autonomy is palpable in these verses: in Fr. 1446A, the “undulating Rooms” of the “Water” provide a kind of hellscape in which “Rest” is “Abhorrent”; in Fr. 1456A, the “Pillage of the Sea” becomes an apt means of describing the barriers to the expression of “a delivered Syllable –.” As so often in Dickinson’s poetry, the sea is pitted against the human function of language, testing the limits of human speech, while the poem also exalts the power of the human mind—“the “Tabernacles of the Minds”—when communicating truth. Fr. 1469A pleads for deliverance from “whatsoever Sea –”, and Fr. 1503B proposes that “the only Vessel that is shunned / Is safe – Simplicity – ” when considering the “Shoal of Thought” that threatens to drown a soul at sea. In each of these cases, the sea not only presents an obstacle to human wishes, but also suggests the possibility that humanity itself may be absorbed into a larger whole. Fr. 1542[B] provides one of Dickinson’s last extended treatments of the sea, and here she concludes that the sea reveals that the afterlife itself may be “abhorred” by human consciousness, “shunned, we must admit it, / Like an adversity.”

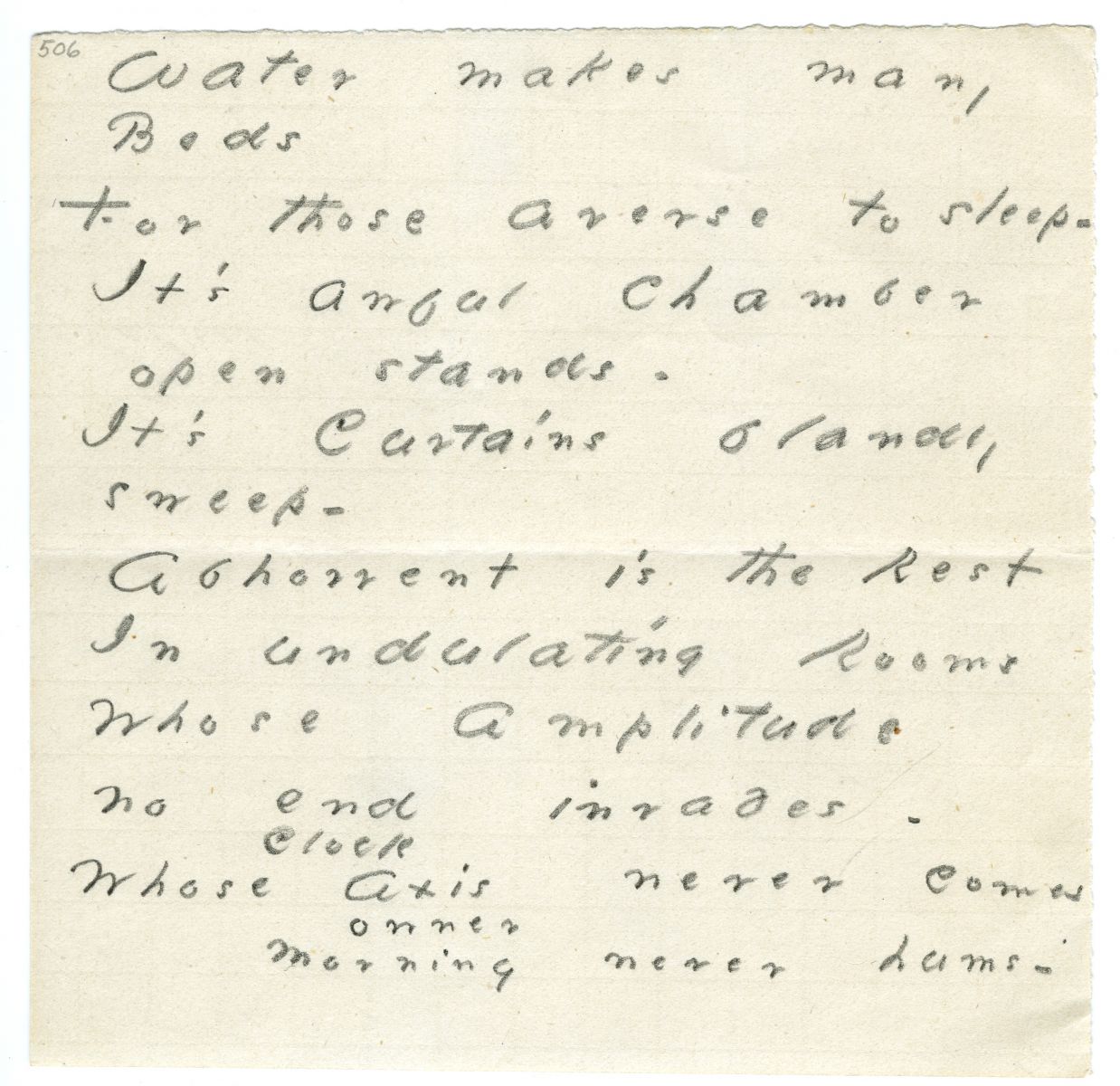

Fr. 1446A, Fr. 1542[B], and Fr. 1689[A] in particular bear closer examination as examples of how Dickinson’s sea poems from this period intersect. Fr. 1446A (MS AC 506) serves notice that Dickinson has developed a powerful and complex response to the materiality of the sea late in her career.

Fig. 2. AC 506, “Water makes many / Beds,” about 1877.

Courtesy Amherst College Archives & Special Collections.

The poem begins with an image of the sea as a bedchamber: “Water makes many Beds / For those averse to sleep –”. These first lines seem to offer a metaphoric reading of the sea by suggesting that water is like the most comfortable and secure place on land for many people, but it shatters that initial suggestion in the second line with its claim that those beds are appropriate for “those averse to sleep –”. The lines point both to the physical discomfort of seasickness, a concrete part of the experience of the sea for many travelers, and, more grimly, to the possibility that one’s aversion to sleep may be overcome by death in the water. These possibilities are rendered still more mutually illuminating in the rest of the poem: “It’s awful chamber open stands – / It’s Curtains blandly sweep – / Abhorrent is the Rest / In undulating Rooms / Whose Amplitude no end invades – / Whose Axis never comes”. Dickinson’s metaphor works specifically to unwind itself in these lines. If the sea is like a bedchamber, it is an extraordinarily unusual one: “awful” in its size and sublimity, “bland” in its disregard for human existence. The “undulating Rooms” of the ocean currents provide an “abhorrent” form of “rest” because they deny the human desire for stability, and the same instability that interferes with the stomach of the seasick traveler also makes the resting place of those drowned at sea unstable and uncertain. Ultimately, this poem seems to question whether the sea will indeed “Give up the dead that were in it” (Rev. 20.13), given that the sea’s “Amplitude” is endless and its “Axis” is inaccessible. The poem takes the sea as analogous to space under human control on land only to dismantle the analogy, leaving its readers with the discomfiting sense that Dickinson’s metaphors have served to illuminate precisely what they cannot contain. If the human mind can say something about the “Water,” it must proceed by acknowledging its own limits, proposing a metaphor and then delineating its own inadequacy, a process not unlike the “negative theology” of religious mystics.

If drowning is suggested through indirect means in Fr. 1446A, it is the explicit subject of Fr. 1542[B]. In this poem, which survives in entirety only in a transcript by Mabel Loomis Todd, the human is effaced in these waves altogether:

Drowning is not so pitiful

As the attempt to rise.

Three times, ’tis said, a sinking man

comes up to face the skies,

And then declines forever

To that abhorred abode,

Where hope and heart part company –

For he is grasped of God.

The Maker’s cordial visage,

However good to see,

is shunned, we must admit it,

Like an adversity.

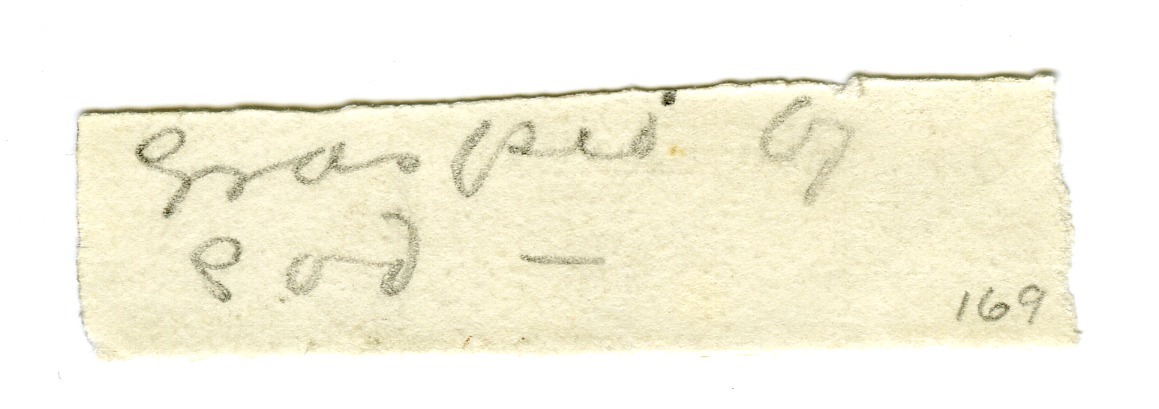

Fig. 3. While the original manuscript of this poem is lost, the above fragment (AC 169, about 1880?) is extant.

Courtesy of the Amherst College Archives & Special Collections.

Drowning, the sea, God, and the acknowledgment of the limits of the human all coalesce superbly in this poem. Indeed, Fr. 1542[B] provides a window into how Dickinson’s religious thought and her prioritizing of the material world come together powerfully in her poetry. “The attempt to rise” suggests the Christian hope of a bodily resurrection, and it is juxtaposed against the idea that drowning—death itself—has its own sort of cosmic dignity, which accounts of human existence that seek to elide or triumph over death leave out. Notably, the “Maker’s cordial visage,” which is “shunned” by humans, is associated directly with the abyss of the ocean, the “abhorred abode.” The physical implacability of the sea and the implacability of mortality are seamlessly joined in this poem. Here the sea is not only like mortality; as in Fr. 1446A, it is a potential metonymic source of mortality, and it undermines the possibility of anthropocentric consolations for the material fact of death, as it suggests that the “Maker’s cordial visage” constitutes cold comfort to one descending to the “abhorred abode” of the ocean floor.

In Fr. 1689[A], Dickinson pushes against the sea as a material expression of the limits of human speech. She begins with a meditation on the unspeakable, asserting that, “To tell the Beauty would decrease / To state the spell demean”. Characteristically for Dickinson, these lines suggest the struggle for an expression adequate to certain intensities of vision, and she seems to be suggesting that expression will always be necessarily inadequate. To capture this inadequacy, she heads out to sea. She proceeds “There is a syllableless Sea / Of which it is the sign / My will endeavors for it’s word / And fails…” The “syllableless Sea” in these lines captures the inability of human thought as structured by language to put the natural world in its place, and it does so by reference to the material properties of the sea, specifically the way in which the currents of the sea resist efforts to fix, name, and subdue locations in the way that is possible on land. At the same time, an awareness of the “syllableless Sea” both compels and enables humans to arrive at a level of knowledge that acknowledges its own incompleteness, and this acknowledgement leads into the final lines of the poem. Dickinson concludes “…but entertains / A Rapture as of Legacies – / Of introspective mines –”. Dickinson here illustrates the method that she had developed for dealing with the limits and paradoxical possibilities of language: if syllables and certainty are not on offer, “A Rapture” may be. Here, as in Fr. 1446A, the metaphor evokes more than it can contain: rooms have walls, and language resolves itself into words and syllables, but Dickinson’s waves have, like St. Augustine’s deity, neither boundaries nor limitable centers, while the syllable-less nature of the sea means that speech always falls short of identifying “it’s word.” Here the sea’s vastness and its indefiniteness come together to suggest the ways in which nature exceeds human cognition.

*

Searching at Sea: The Arc of Dickinson’s Oceanic Poetry across Her Career

Fig. 4. Lehmann, A. The Sea.

Engraving on cloth. Frame: 28 in x 37 in; 71.1 cm x 94 cm; Image: 13 1/2 in x 22 1/2 in; 34.3 cm x 57.1 cm. AC EDM 2003.179.

Collection of the Emily Dickinson Museum, Transfer from Martha Dickinson Bianchi Trust.

If the three poems I have just discussed function as a culmination of Dickinson’s treatment of the sea, they reflect the fact that throughout her career, the sea appears in moments of interpretive openness and an occlusion of human agency. When we track the wider sweep of her career, Dickinson’s seas function metaphorically and metonymically to suggest erotic abandonment (Fr. 269A), impersonal natural force (Fr. 387A), an all-enveloping whole (Fr. 255A, B; Fr. 219A, B; Fr. 913A; Fr. 1275[A], B, C), indeterminate age (Fr. 1255A), an enticing would-be devourer (Fr. 656A), and the infinite and uncertain (Fr. 1446A); finally, as seen above, drowning suggests a loss of self-consciousness in the presence of the divine (Fr. 1542[B]). Even as Dickinson shows that the sea’s materiality cannot be contained in poems across her oeuvre, these very poems move back and forth between an incisive critique of human presumptions of agency and a compelling portrait of the intellectual and physical nimbleness needed to maintain one’s balance in a force that exceeds human power to contain. Although it would be too much to credit Dickinson with foreseeing a situation where human agency can alter sea levels around the planet, Dickinson’s poems suggest a human response to the power of the sea that embraces the humility necessary to respond to such an unprecedented situation.

One can find multiple resonances of the sea even in the briefest of Dickinson’s lyric poems. What draws these numerous references together is a sense that Dickinson is looking beyond the boundaries of the human world—beyond that which we have the power to express, even metaphorically—to what David Francis has described as “moving from the false necessity of naming something compatible with humanity…to the accurate necessity of letting no thing inhabit language” (272), pressing up against what Sharon Cameron called in Lyric Time the “human limit” (191) of language.

Even after noting the power with which Dickinson writes about the sea in the later years of her career, we might still be surprised to note that Dickinson’s references to the sea are present from the very earliest poems that are available to us. Her earliest poem dedicated to the sea appears as number 3 (two ms versions, A and B; B quoted below) in R. W. Franklin’s variorum numbering of her poems, and it illustrates the way in which Dickinson can extend the treatment of the sea in popular forms. Calling to mind the New England tradition of hymnody that draws on the wind and the wave as a metaphor, Dickinson writes in her first stanza:

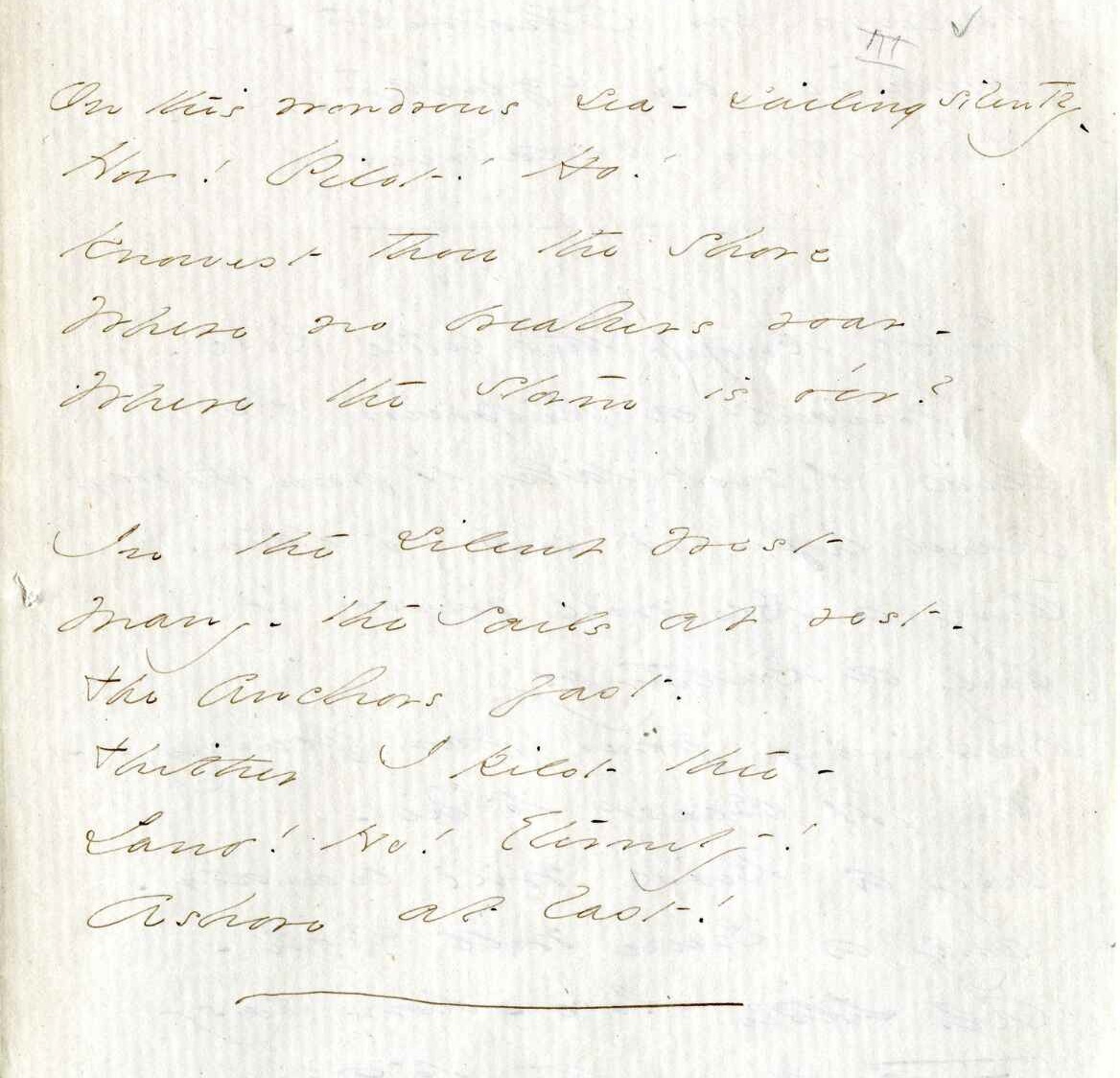

On this wondrous sea – sailing silently –

Ho! Pilot! Ho!

Knowest thou the shore

Where no breakers roar –

Where the storm is o’er? (Fr. 3B, MS AC 82-7/8)

Fig. 5. AC 82-7/8, “On this wondrous sea – sailing silently –,” about summer 1858.

Courtesy of Amherst College Archives & Special Collections.

This poem echoes the commonplace image of God as the Pilot upon whom the wandering soul relies, and readers of Moby-Dick will recognize the treatment of the sea in Father Mapple’s sermon and the psalm that his congregants sing at the start of the service in the whaleman’s chapel (48). A poem like this one sets the stage for the later moments in Dickinson’s career when the image of a divine protector leading sailors across a hostile sea is replaced by images of the sea in which the divine and the terrifyingly inhuman become merged, and in which neither the sea nor the deity can convincingly be anthropomorphized. In 1854, Dickinson finds a figure for distance in the sea, writing “Yet do I not repine / Knowing that Bird of mine / Though flown – / Learneth beyond the sea / Melody new for me / And will return” (Fr. 4A). Here Dickinson inaugurates what will become a compelling strand in her poetry: the contrast between the power and distance associated with the sea and the fragility and endurance of birds across these distances. Dickinson would pick up this imagery in 1862, writing in Fr. 314B (which provides one of the most frequently quoted lines in her poetry, the assertion that “ ‘Hope’ is the thing with feathers –”) that she had heard the song of a bird “in the chillest land – / And on the strangest Sea –,” illustrating the confluence of nature at its most sublime with nature at its most vulnerable. The sea appears in these early poems as a source of danger, with the ability to come to terms with the threat functioning as the price of survival.

Dickinson’s invocations of the sea grow in their complexity across her career. In the earliest poems, she seems primarily invested in noting the sea’s power and status as a central instance of the sublime (including both as an obstacle for the aspiring soul to overcome and as a model for that aspiring soul); it does not take long for her to work towards subtler psychological shading on the one hand and more physical detail on the other. In Fr. 143B (MS H 10), Dickinson writes,

Exultation is the going

Of an inland soul to sea –

Past the Houses –

Past the Headlands –

Into deep Eternity –

Bred as we, among the mountains,

Can the sailor understand

The divine intoxication

Of the first league out from Land?

.png)

Fig. 6. H 10, “Exultation is the going,” about early 1860.

Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Here, the sea becomes something other than an obstacle for a divine “Pilot” to overcome: rather it stands in for the experience in which a human consciousness becomes lost in something more powerful than itself. The “inland soul” resembles the greenhorn sailor so common in both fictional and non-fictional accounts of first voyages at sea (Herman Melville’s Redburn, and, to a lesser degree, Typee partake of this tradition), and it moves steadily from the experiences that orient it to the world to the disorienting “divine intoxication / Of the first league out from Land”. Here the sea is essential to Dickinson’s vision precisely because of its capacity to reorganize and decenter human perceptions, and if this decentering is unsettling, it is also exhilarating. Similarly, a poem like Fr. 152A reminds readers that not every craft is brought safely to port by its pilot’s ministrations: “’Twas such a greedy, greedy wave / That licked it from the Coast – / Nor ever guessed the stately sails / My little craft was lost!”

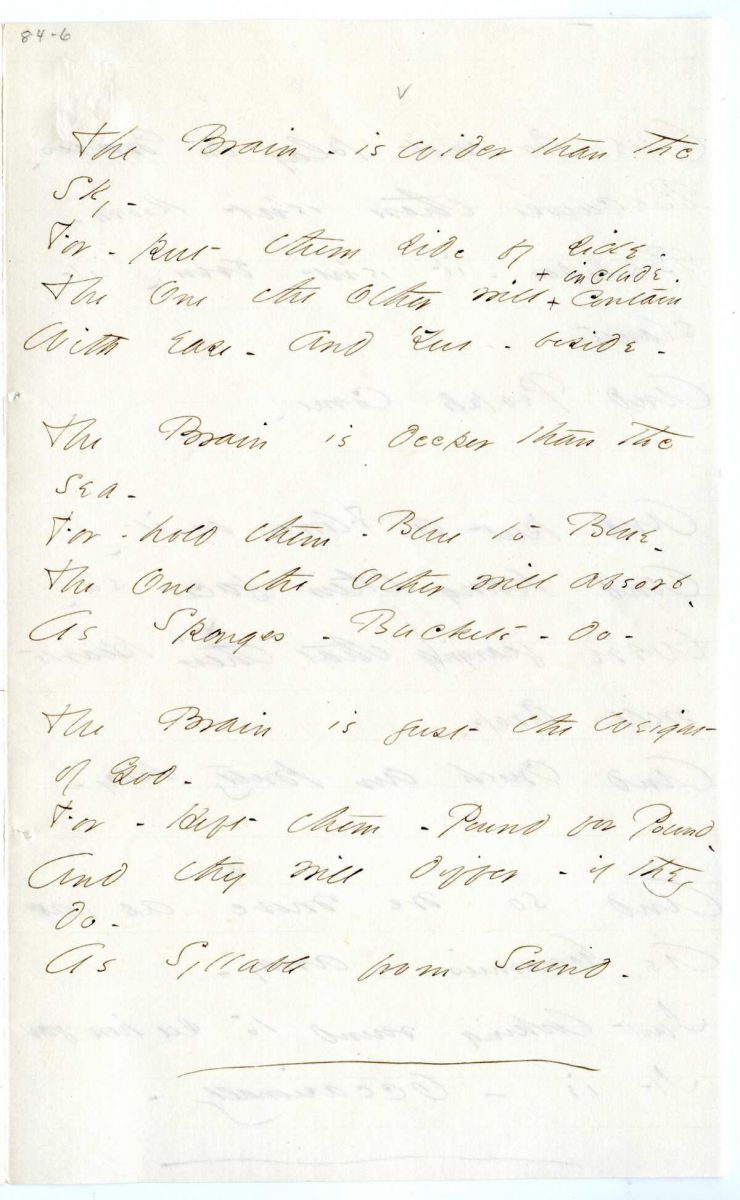

The diversity of Dickinson’s treatment of the sea in the middle portion of her career is exemplified in several poems written, according to Franklin, in 1863. In Fr. 598A (MS AC 84-5/6), one of Dickinson’s most frequently anthologized poems, she inverts the relationship between human consciousness and the sea on display in Fr. 143A, B, suggesting that “The Brain is deeper than the sea – / For – hold them – Blue to Blue – / The one the other will absorb – / As Sponges – Buckets – do ”.

Fig. 7. AC 84-5/6, “The Brain – is wider than the / Sky –,” about summer 1863.

Courtesy of Amherst College Archives & Special Collections.

Dickinson invokes the size and power of the sea in this poem, but here it is in service of what might initially seem to be an idealistic conceit: the entire cosmos, even the unfathomable leagues of the sea, can be absorbed into human consciousness. And yet, the metaphor is more complex than it initially appears. The human brain (not mind), may be able to absorb the sea “As Sponges – Buckets – do –”, thus suggesting the enormous power of human consciousness, but the fact that consciousness is located in a part of the human physical anatomy also reminds us of how tenuous this power is. The sea contains, as Dickinson knew well and acknowledged from her earliest poems, an ample quantity of human bodies and brains, and thus we can see substantial human fragility hidden behind the audacious claims for the brain’s absorptive powers. This emphasis on human fragility joined paradoxically to human power reproduces the way in which Dickinson makes the power of the sea a precondition for understanding the persistence of the birds in the midst of storm: oceanic power is a necessary backdrop for the performance of endurance and courage. Like the ocean-going birds of Dickinson’s early poems, humans must struggle to maintain their psychological balance in an environment that they cannot fully control, and maintaining this balance requires the recognition that humans face environmental constraints on their wishes and impulses.

Precisely this capacity of the sea to engulf the human body and brain appears in another poem from 1863, Fr. 631A (MS H 90).

.png)

Fig. 8. H 90, “Me prove it now – Whoever / doubt,” about the second half of 1863.

Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

In this poem, Dickinson traces in agonizing detail the process of drowning, concluding: “The River reaches to my Mouth – / Remember – when the Sea / Swept by my searching eyes – the last – / Themselves were quick – with Thee!” Here love and mortality come together in the image of drowning, with the conclusion suggesting that love persists in the moment of death, even as the sea illustrates the inevitability of mortality and loss. Dickinson plays with the boundaries between human cognition and natural processes here, as she would in her later poems, with the line “Swept by my searching eyes,” which both suggests that the speaker’s eyes are sweeping the sea, and that the sea itself has continued to surge past her eyes, oblivious to her human agenda and her life, even as her eyes—“quick – with Thee!”—retain their focus for a last moment before death.

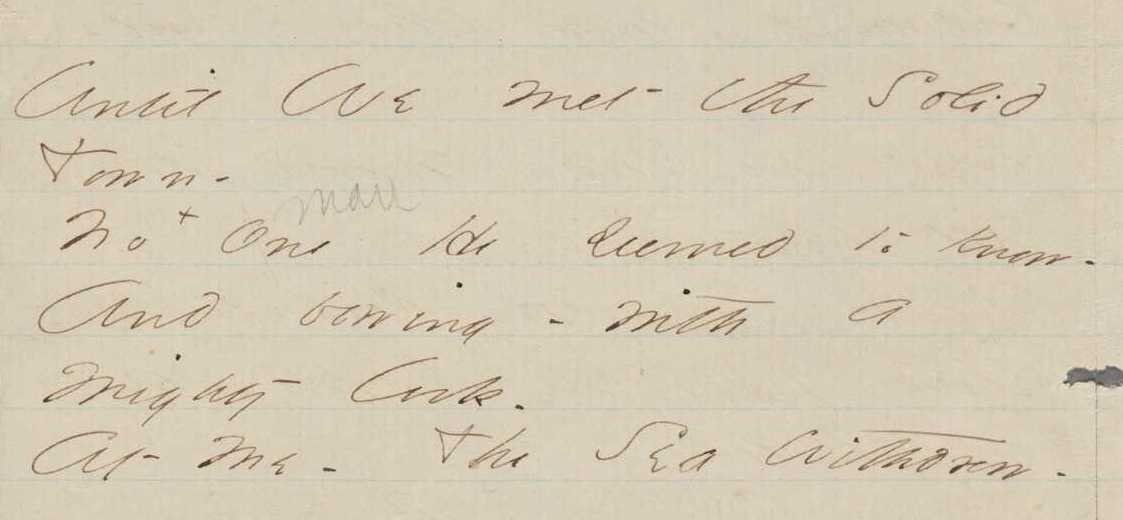

Both tendencies are on display in a third poem from 1863, Fr. 656A (MS H 382), a whimsical poem that playfully captures both the sea’s power and the capacity for mastery in human consciousness. In this poem, longer than most of Dickinson’s works, she moves between lighthearted images of a walk with her dog on the shore and “Mermaids in the Basement,” and the grimmer possibility of being drowned by the incoming tide. Strikingly, the speaker avoids drowning only because the sea, figured here as a courtly suitor, makes the choice to release her: “And bowing – with a Mighty look – / At me – The Sea withdrew –”.

Fig. 9. H 382 (detail), “I started Early – took my / Dog –,” about the second half of 1863.

Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University.

The sea’s withdrawal is not a matter of human desire, but of its own motion: the tides decide, not the speaker. The line from this expression of the sea’s independence of human desire and of the limits of the human when confronted by the sea would ultimately find its expression in the “undulating Rooms” of Fr. 1446A, the “abhorred abode,” of Fr. 1542[B], and the “syllableless sea” of Fr. 1689[A].

*

Dickinson’s Post-human Seas

Fig. 10. Turner, Joseph Mallord William (after). Lucerne.

Engraving on paper. Sheet: 20 in x 26 in; Plate: 16 ½ in x 23 in; Image: 11 ½ in x 18 ½ in. AC EDM 2003.90.

Collection of the Emily Dickinson Museum, Transfer from Martha Dickinson Bianchi Trust.

As we have seen, Dickinson’s use of the sea intensifies in her later poems, and builds on a recognition of the sea’s materiality that she was already exploring in the 1860s, as she finds the connections with mortality and the ways in which the sea provides a rebuke to human egotism to be particularly compelling. Dickinson provides a parallel, but distinct, experience in her late poems on the sea. The sea remains up until her last years a reminder of the limits of human desire and potential and of the necessity of confronting and acknowledging these limits, which not even a benevolent deity offers the possibility of easily transcending by this stage in Dickinson’s career.

Dickinson’s experimental treatment of the sea thus resides in how she shifts the epistemological center of her poems when the sea and the human collide. Dickinson allows the sea to relocate the center of her poetry outside human wishes and desires. Even where she uses metaphors from the shore—“undulating rooms,” to refer to an example that I have discussed at length above—the point is the inadequacy of the metaphor, the degree to which oceanic waves are more than the human world that seeks them out as analogies, and to which the analogies themselves expose their own shortcomings.

Recognizing the power of the sea may be a requirement for the human to regain its just dimensions, and the sea’s vastness provides us with the necessary material to comprehend our own limits. Simultaneously, Dickinson’s emphasis on the ability of birds and brains alike to come to terms with the sea offers a model for a humanism that finds itself precisely in losing its more imperial pretensions to human dominance. In her late poetry of the sea, Dickinson realizes most fully an obsession that spanned her career as poet: the material realities of the ocean and travel upon it. In so doing, she demonstrated both the sea’s remarkable fecundity as a source of metaphor and its capacity to undo the very analogies it enabled.

Brian Yothers, University of Texas at El Paso

Note

The images of the artworks included here are from Austin Dickinson’s art collection. These works may be viewed in context at “Art at the Evergreens,” available on-line through the Five College Art Museums/Historic Deerfield Collection Database: http://museums.fivecolleges.edu/info.php?museum=ac&page=0&v=2&s=&type=ext&t=objects&f=&d=&id_number=Ac+edm&op-earliest_year=%3E%3D&op-latest_year=%3C%3D

Works Cited

Blum, Hester. “The Prospect of Oceanic Studies.” PMLA, vol. 125, no. 3, 2010, pp. 670-77.

Cameron, Sharon. Lyric Time: Dickinson and the Limits of Genre. Johns Hopkins UP, 1981.

Dickinson, Emily. The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Reading Edition. Edited by R. W. Franklin. Belknap/Harvard UP, 1998.

---. The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson. Edited by Thomas H. Johnson. Little, Brown, 1961.

The English Bible: King James Version, The New Testament and Apocrypha. A Norton Critical Edition. Edited by Gerald Hammond and Austin Busch. W. W. Norton, 2012.

Francis, David. “The Giant at the Other Side: Emily Dickinson and the Inhuman.” The Emily Dickinson Journal, vol. 5, no. 2, 1996, pp. 267-72.

Freeman, Margaret H. “Nature’s Influence.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Edited by Eliza Richards. Cambridge UP, 2013.

Madigan, Francis V., Jr. “Mermaids in the Basement: Emily Dickinson’s Sea Imagery.” Greyfriar: Siena Studies in Literature, vol. 23, 1982, pp. 39-56.

Melville, Herman. Moby-Dick; or, The Whale. 2nd Norton Critical Edition. Edited by Hershel Parker and Harrison Hayford. W. W. Norton, 2002.

Miller, Cristanne. Reading in Time: Emily Dickinson in the Nineteenth Century. U of Massachusetts P, 2012.

Image Credits

Fig. 1. Cook, R. Seascape with Fog. Oil on canvas. Frame: 36 1/2 in x 33 1/2 in x 4 1/2 in; 92.7 cm x 85.1 cm x 11.4 cm; Sight: 23 1/2 in x 20 1/2 in; 59.7 cm x 52.1 cm. AC EDM 2003.216. Collection of the Emily Dickinson Museum, Transfer from Martha Dickinson Bianchi Trust. For link, see: http://museums.fivecolleges.edu/detail.php?museum=&t=objects&type=ext&f=&s=&record=133&id_number=Ac+edm&op-earliest_year=%3E%3D&op-latest_year=%3C%3D

Fig. 2. AC 506, “Water makes many / Beds,” about 1877. Courtesy Amherst College Archives & Special Collections. For link, see: https://acdc.amherst.edu/search/Water+makes+many+beds

Fig 3. While the original manuscript of this poem is lost, the above fragment (AC 169, about 1880?) is extant. Courtesy of the Amherst College Archives & Special Collections. For link, see: https://acdc.amherst.edu/view/asc:1433

Fig. 4. Lehmann, A. The Sea. Engraving on cloth. Frame: 28 in x 37 in; 71.1 cm x 94 cm; Image: 13 1/2 in x 22 1/2 in; 34.3 cm x 57.1 cm. AC EDM 2003.179. Collection of the Emily Dickinson Museum, Transfer from Martha Dickinson Bianchi Trust. For link, see: http://museums.fivecolleges.edu/detail.php?museum=&t=objects&type=ext&f=&s=&record=93&id_number=Ac+edm&op-earliest_year=%3E%3D&op-latest_year=%3C%3D

Fig. 5. AC 82-7/8, “On this wondrous sea – sailing silently –,” about summer 1858. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives & Special Collections. For link, see: https://acdc.amherst.edu/view/asc:15595/asc:15604

Fig. 6. H 10, “Exultation is the going,” about early 1860. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University. For link, see: http://www.edickinson.org/editions/1/image_sets/235381

Fig. 7. AC 84-5/6, “The Brain – is wider than the / Sky –,” about summer 1863. Courtesy of Amherst College Archives & Special Collections. For link, see: https://acdc.amherst.edu/view/asc:1457/asc:1469

Fig. 8. H 90, “Me prove it now – Whoever / doubt,” about the second half of 1863. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University. For the link, see: http://www.edickinson.org/editions/1/image_sets/235950

Fig. 9. H 382 (detail), “I started Early – took my / Dog –,” about the second half of 1863. Courtesy of the Houghton Library, Harvard University. For whole ms as a link, see: http://www.edickinson.org/editions/1/image_sets/235928 and the following page: http://www.edickinson.org/editions/1/image_sets/235929

Fig. 10. Turner, Joseph Mallord William (after). Lucerne. Engraving on paper. Sheet: 20 in x 26 in; Plate: 16 ½ in x 23 in; Image: 11 ½ in x 18 ½ in. AC EDM 2003.90. Collection of the Emily Dickinson Museum, Transfer from Martha Dickinson Bianchi Trust. For link, see: http://museums.fivecolleges.edu/detail.php?museum=&t=objects&type=ext&f=&s=&record=208&id_number=Ac+edm&op-earliest_year=%3E%3D&op-latest_year=%3C%3D