- Reading at Home: Emily Dickinson's Domestic Contexts

- Introduction by Gabrielle Dean

- “I am glad there are Books. They are better than Heaven”: Religious Texts in the Dickinson Family Libraries by Jane Wald

- Letters to the World: Popular Manuscript Circulation in the Nineteenth Century and Emily Dickinson’s Handwritten Verse by Thomas Lawrence Long

- “The Last Rose of Summer”: How Emily Dickinson Read and Rewrote the Favorite Song of the Nineteenth Century by Gabrielle Dean

- Contributors

“I am glad there are Books. They are better than Heaven”: Religious Texts in the Dickinson Family Libraries by Jane Wald

“They… address an eclipse”: Belief at Home

Emily Dickinson came of age in an orthodox household steeped in the Puritan theology that was gradually unraveling in the face of new varieties of Protestant experience. Like most Amherst families, the Dickinsons held daily religious observances in their home, but Emily was a less than enthusiastic participant: “They are religious, except me,” Dickinson wrote of her family, “and address an eclipse, every morning, whom they call their ‘Father’” (L 261, 2:404-05) (figs. 1-5).

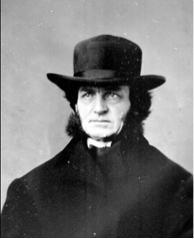

Figure 1. Edward Dickinson. Portrait, 1853, photographer unknown. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

Figure 2. Emily Norcross Dickinson. Daguerreotype portrait, ca. 1847, by William C. North. Monson Free Library.

Figure 3. William Austin Dickinson, ca. 1850, photographer unknown. Amherst College Archives & Special Collections.

Figure 4. Emily Dickinson. Daguerreotype portrait, ca. 1847, photographer unknown. Amherst College Archives & Special Collections.

Figure 5. Lavinia Norcross Dickinson. Dagurreotype portrait, 1852, by J.L. Lovell. Dickinson family photographs, MS Am 1118.99b (27). Houghton Library, Harvard University.

In her teen years, a wave of religious revivals moved through New England and through Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, which she attended for a single year. One by one, her friends and family members made the public profession of belief in Christ that was necessary to become a full member of the church.

Although she agonized over her relationship to God, Dickinson ultimately did not join the church: “I feel that the world holds a predominant place in my affections. I do not feel that I could give up all for Christ, were I called to die” (L 13, 1:36-38). By the time she reached her thirties, Emily Dickinson had stopped attending services altogether, a decision that coincided with her most productive writing years, the national tragedy of Civil War, the threat of losing her vision, a telling emotional crisis of an unknown nature, and increasing reclusiveness.

A persistent misconception about Dickinson’s refusal to become a full member of the church and to style herself a “pagan” is that she rejected God altogether, cloistered herself in her room, took little notice of the world beyond her four walls, and composed poem after poem for no one but herself. On the contrary—and despite her absence from public religious life—Dickinson’s letters and poems chronicle a lifelong struggle with issues of faith and doubt, suffering and salvation, nature and deity, mortality and immortality. An examination of the religious texts on the shelves of her family’s libraries could cast more light on Emily Dickinson’s personal theological explorations. My aim here is to begin this important task. First, I will sketch in broad strokes the contents of the libraries at the family Homestead, where Emily Dickinson lived most of her life, and at The Evergreens, her brother’s house next door. Next, I will offer a profile of religious texts associated with various family members, which provides insight not only into their personal interests but also into the broader contours of nineteenth-century American religious movements. Finally, I will examine two books in particular that suggest broad interaction with contemporary theology in the Dickinson households.

“This then is a book!”: Literary Context And Household Libraries

Emily Dickinson’s patterns as a reader naturally have important implications for her choices as a writer. The problem of how to place a reclusive poet in meaningful context has plagued scholars and readers ever since Dickinson’s first anonymous publications. Over the past several decades, however, a scholarly focus on more thorough accounts of Dickinson’s context—social, literary, political, material—has offered some hope of filling in Dickinson’s elusive “omitted center.” Beginning with Jack Capps’ 1966 survey, Emily Dickinson’s Reading, scholars have combed the texts Emily Dickinson consumed for direct and indirect literary influences on her poetic art. Others have extended this effort by describing as accurately as possible the cultural milieux of Dickinson’s opus to better understand the magnitude of her achievement. Simultaneously, others have probed Dickinson’s self-conscious connections to women’s literature, the American Civil War, religion, contemporary understandings of science and the natural world, and more. Emily Dickinson as a reader and the books she had at hand have recently attracted increased attention.[2]

To be sure, the Dickinson family’s libraries offer an exceptional view of Dickinson’s personal literary context, for they contained the books she lived with every day. The libraries’ physical dispersal in the twentieth century, however, has made it challenging for researchers to study the original collections and assess their import.

Figure 6. The Homestead. Photograph by Michael Medeiros. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

Figure 7. The Evergreens. Photograph by Michael Medeiros. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

Dickinson was born, wrote poetry, and died in the family homestead built in 1813 by her attorney grandfather (fig. 6). In 1855, after an absence of fifteen years, the Dickinson family settled back into the Homestead while construction of a new home for Austin and his bride-to-be Susan began on the adjacent lot. Their daughter, Martha Dickinson Bianchi (by 1914 the last surviving family member), sold the Homestead in 1916 but continued to live at The Evergreens until her own death in 1943 (fig. 7). Martha moved her aunt’s manuscripts, family furnishings, keepsakes, and books from the Homestead to The Evergreens, assembling a memorial collection in what she called the “Emily Room” (figs. 8-10).

Figure 8. Martha Gilbert Dickinson Bianchi, ca. 1900. Photographer unknown. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

Figures 9 and 10. Emily Dickinson’s furniture in the “Emily Room” at The Evergreens, 1934. Photographer unknown. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

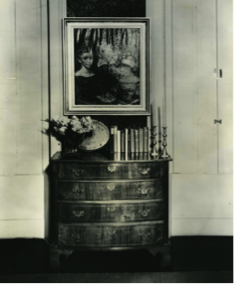

Wishing to secure Dickinson’s literary legacy, Martha’s heirs, Alfred and Mary Hampson, agreed in 1950 to transfer Emily’s manuscripts and personal effects, selected family furnishings, and approximately six hundred volumes—personal copies belonging to Emily Dickinson or titles of significance to her but owned by other members of the family—to Harvard University’s Houghton Library. Upon her death in 1988, Mary Hampson established the Martha Dickinson Bianchi Trust to care for The Evergreens and its contents, and left remaining Dickinson family papers and some 2,700 additional volumes to Brown University where they now reside in the John Hay Library (fig. 11).

Figure 11. Count and distribution of books from the Dickinson family libraries.

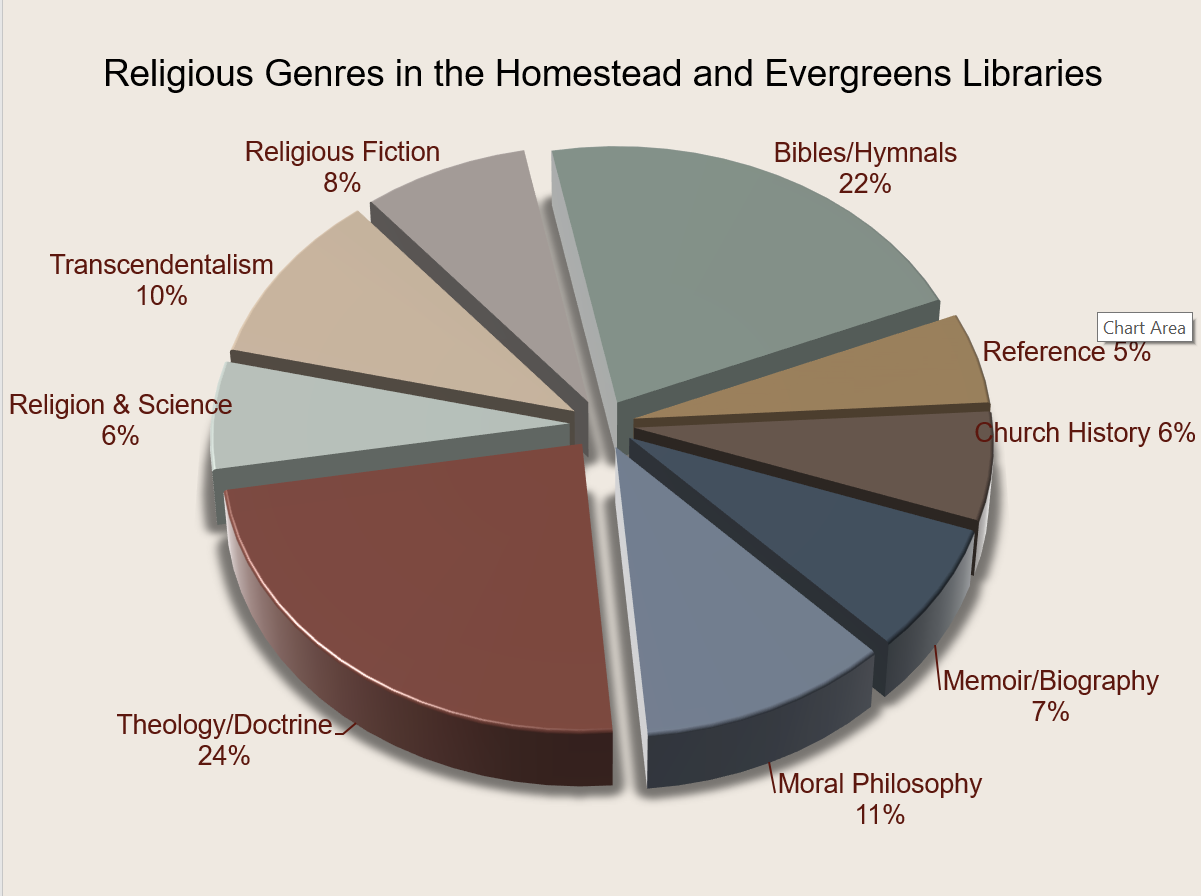

Emily Dickinson’s manuscripts are increasingly available to scholars and the public. The Dickinson Electronic Archive has made numerous resources available since 1994. Harvard University’s Houghton Library is systematically digitizing its six-hundred-volume collection of Dickinson family books (www.oasis.lib.harvard.edu/oasis/deliver/~hou00321) as well as its collection of Dickinson letters and manuscripts. Amherst College has digitized its entire Dickinson manuscript collection (www.acdc.amherst.edu/collection/ed). The collaborative online Emily Dickinson Archive (www.edickinson.org), led by Harvard University Press, now furnishes images of all poem manuscripts in the collection edited by Ralph Franklin in 1998. These projects offer opportunities for many new robust research projects, including closer examination of a subset of Dickinson family book holdings that influenced Emily Dickinson’s poetics and theology—religious texts in the two family libraries (figs. 12-13).[3]

Figure 12. Library at the Dickinson Homestead. Photograph by Michael Medeiros. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

Figure 13. Library at The Evergreens. Photograph by Michael Medeiros. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

A preliminary analysis of the combined Brown and Harvard inventories reveals that, at the time of Emily Dickinson’s death in 1886, the two family libraries contained close to 1,600 volumes. Yet, the formation, use, and contents of these libraries have received little attention, due in part to the prominence of the Houghton collection of six hundred hand-picked books and the relative inaccessibility of the majority of family books at Brown University.[4]

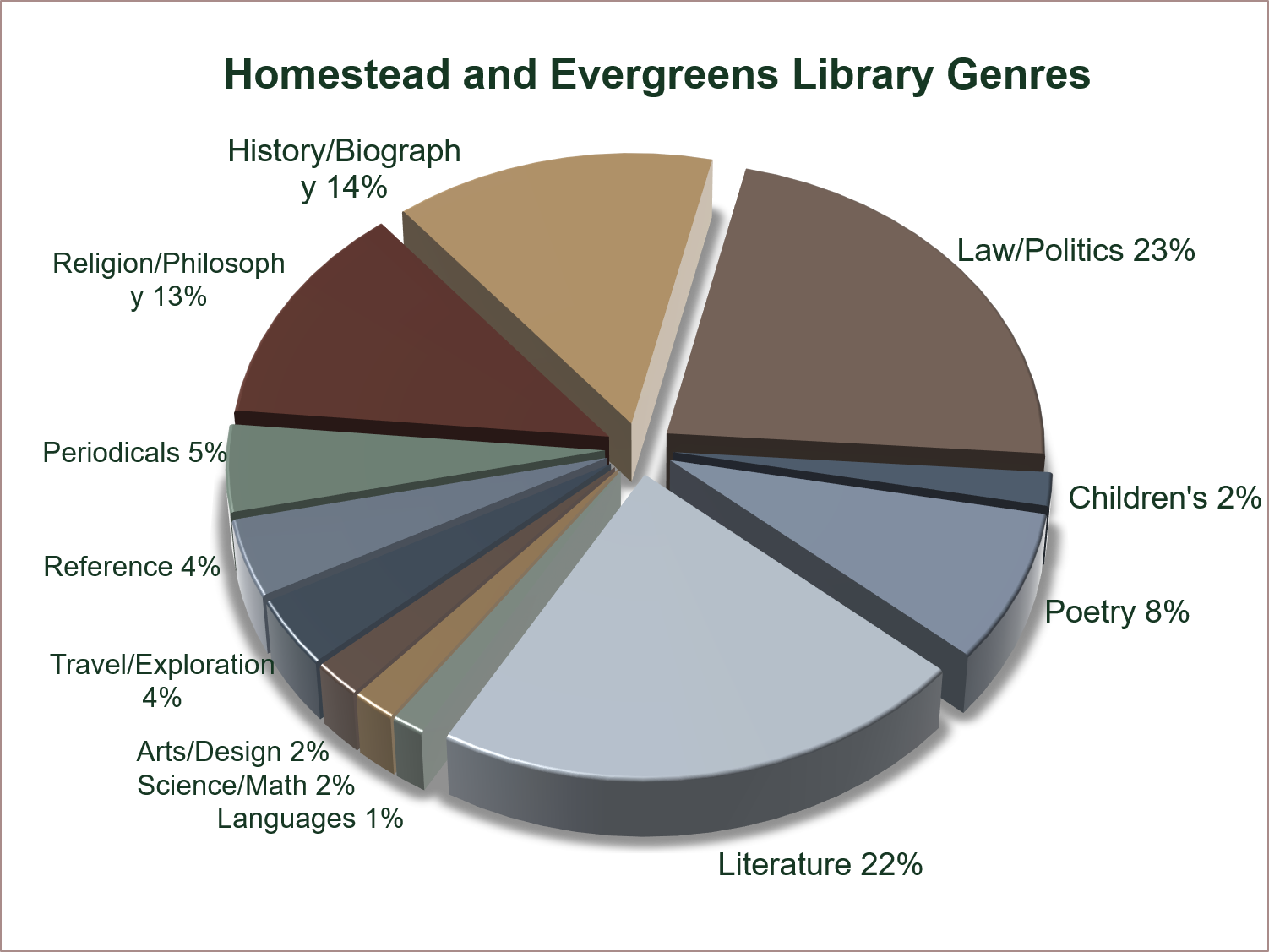

Not surprisingly, the leading genre on the shelves was literature—fiction, poetry, and children’s stories comprised a third of all books. Almost a quarter of library holdings were books related to law, government, and politics. There were a couple of hundred books on religion, theology, and natural philosophy. History and biography accounted for a similar proportion. Family subscriptions to periodicals—including the Atlantic Monthly, Scribner’s Monthly, and Harper’s—claimed five percent of library shelf space. A lesser smattering of instruction books in languages, science, and mathematics sat alongside a clutch of art and reference books and exploration narratives (fig. 14).

Figure 14. Genres in the Dickinson family libraries in 1886.

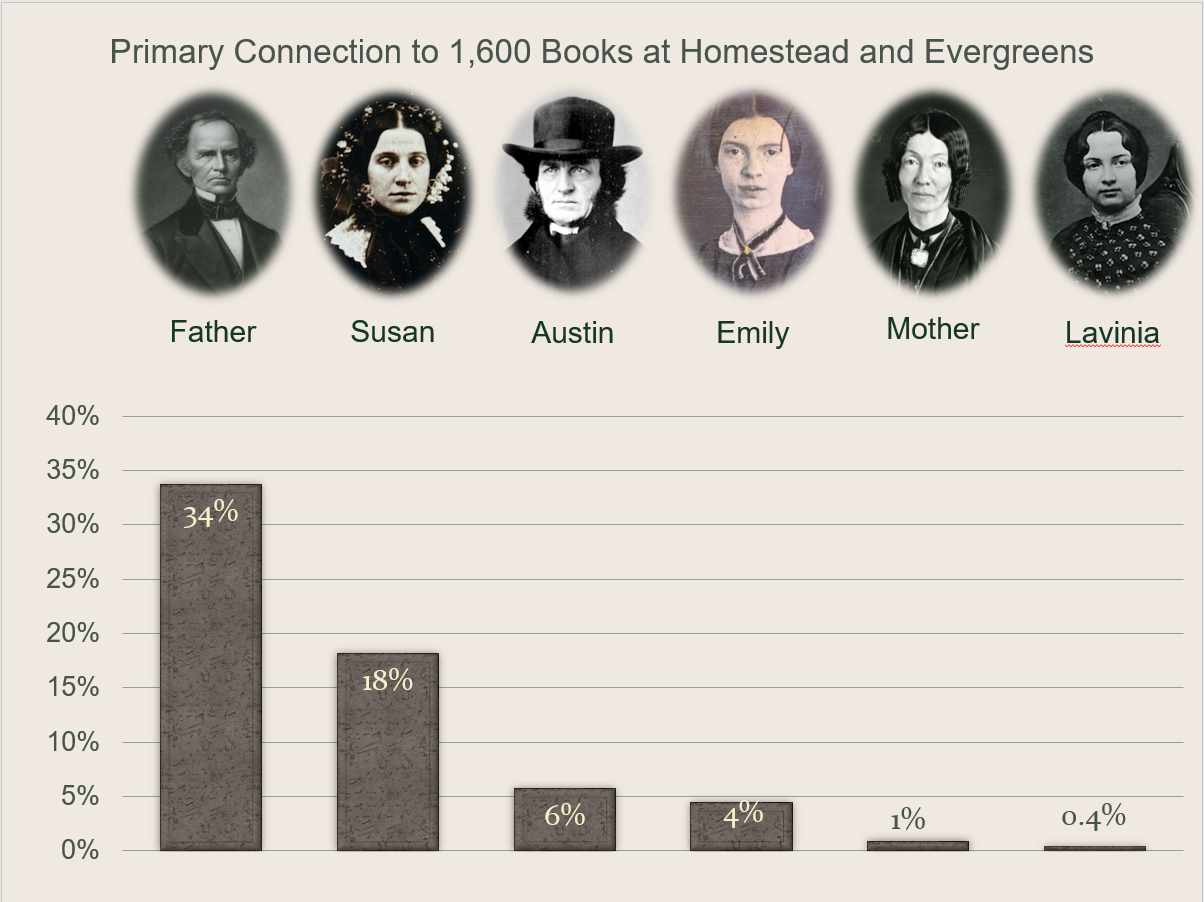

Despite the fact that the family libraries were compiled and used by four generations of Dickinsons, it is possible to postulate—by analyzing inscriptions, correspondence, dates of publication, and genre—which member of the family purchased, owned, or was most closely associated with each of 1,400 volumes, or about 90% of the collection (fig. 15).

Figure 15. Primary connection of 1600 titles to Dickinson family members.

The prize for book acquisition in the Dickinson family goes to Edward Dickinson, who, according to his daughter “only reads on Sunday—he reads lonely & rigorous books” (L342a, 2:472-74). A lawyer, legislator, and Amherst College treasurer, Edward Dickinson built a professional library of legal, political, and economic works: at least 230 volumes of Congressional debates and proceedings, diplomatic correspondence, executive documents of the U.S. House of Representatives, reports on trade and agriculture, and the like. Another 300 books were heavily weighted toward history, exploration narratives, orthodox religious texts, and literary classics. In total, no fewer than 540 books from the family library can be linked with Edward Dickinson.

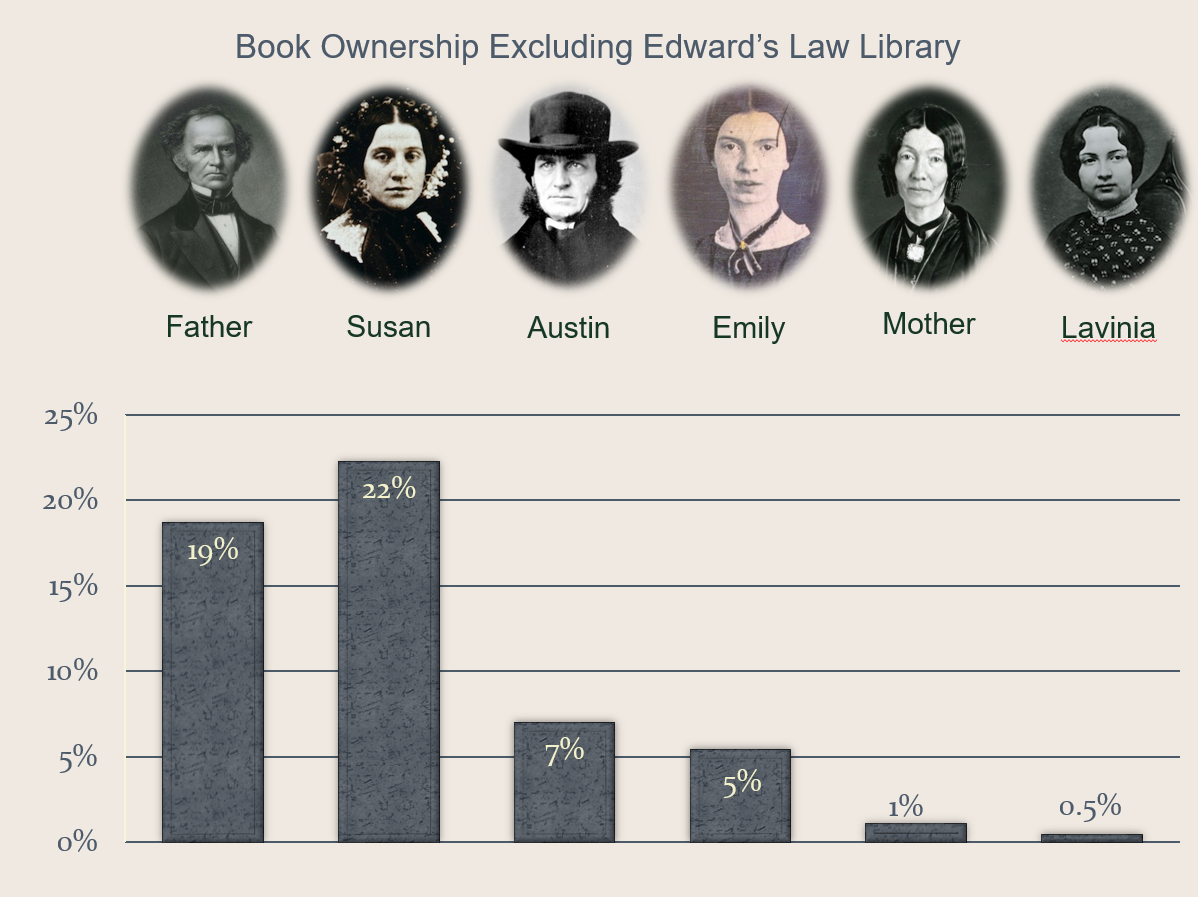

Emily’s confidante and sister-in-law, Susan Gilbert Huntington Dickinson, was known for her intelligence and cultured interests. Her personal book holdings rivaled those of her father-in-law Edward, omitting his Congressional records (fig. 16).

Figure 16. Primary connection of titles to Dickinson family members, excluding Edward Dickinson’s law library.

Upon her engagement to Austin Dickinson, Sue’s brother Frank promised a wedding present of fifty books of her choice, many of which can be identified from her application of an elegant bookplate inside the cover with the inscription of the date of acquisition in her hand (fig. 17). Under Sue’s direction, The Evergreens filled with literary classics and contemporary fiction, poetry, art, and eclectic theological and philosophical treatises. “Austin’s taste,” as described by his daughter Martha, “was strongly individual and often diverged until the absorption of his legal professional work . . . left him little leisure for even the books he cared for most.” Martha indicated that “many were given him by Sue” (Bianchi, [Family Books]). As an attorney and Amherst College treasurer like his father, Austin amassed a prodigious professional library housed in his Palmer Block offices, which was lost to fire in 1888, along with numerous documents important to Amherst town history.

Figure 17. Susan Huntington Gilbert’s bookplate. Emily Dickinson Museum collection.

Despite her feeling that books are “the strongest friends of the soul,” Emily Dickinson seems to have had an ambiguous relationship to book ownership (Sewall, Life, 76). Only about 5% of the titles in the family libraries can be distinguished specifically as her personal property. But, obviously, she had access to the full family libraries as well as to holdings of Amherst College’s library. She traded books with friends, belonged to reading clubs, and even indulged in hiding contraband books from her parents. Niece Martha Dickinson Bianchi observed that Austin, Sue, and Emily shared and “read the same books with apparent delight,” and that few [of Emily’s own books] were written in—gifts or especial favorites only being claimed as personal” (Bianchi, [Family Books]). More important to Emily Dickinson than the book as object or personal possession was the text.

The “household of faith”: Varieties of Religious Experience in the Dickinson Households

Before looking at a few of the religious texts in the family libraries, some observations about the spiritual views of the Dickinson siblings and their sister-in-law may be helpful. Austin, Emily, and Lavinia—each in his or her own way—merged the rationalism of their parents’ generation with Calvinist insistence on the depravity of human nature into a romantic and sentimental confidence in the perfectibility of humankind. In Amherst at mid-century, close upon the heels of a general religious revival, it may have been difficult, but not impossible, for members of one of the town’s most influential and orthodox families to buck the religious status quo. Clearly, the Dickinson siblings (and perhaps even their father) tested the boundaries of religious orthodoxy and found their theological voyages less than smooth sailing.

Martha Dickinson Bianchi reported that in young adulthood “both Emily and Austin seem to have inwardly departed from a theology that would now hold Fundamentalism to be heresy” (Bianchi, Face to Face, 133-34). Austin, like Emily, expressed grave doubts about the church’s insistence that only those who confessed faith in Christ were to be saved from sin and inherit eternal life. He stated these misgivings in a long letter to Susan’s sister Martha in 1852:

I see them [mankind] marshaled in mighty hosts, yet under different banners, and marching on to the word of their several leaders, whom they believe, each his own, have received from the Omnipotent himself the true and only true chart of the route to knowledge, to happiness everlasting &to him. And now new doubts encompass me, for if either, and only one, which is right? . . . I ask myself, Is it possible that God, all powerful, all wise, all benevolent, as I must believe him, could have created all these millions upon millions of human souls, only to destroy them? That he could have revealed himself & his ways to a chosen few, and left the rest to grovel on in utter darkness? I cannot believe it. I can only bow & pray, Teach me, O God, what thou wilt have me do, & obedience shall be my highest pleasure (A. Dickinson, qtd. in Sewall, Life, 106).

Austin’s views about spiritual matters were suspiciously progressive. In a draft of his 1856 confessional statement, Austin acknowledged that he had once—but no longer—considered religion “‘a delusion, the bible a fable, life an enigma’” (qtd. in Habegger, Wars, 336). Elsewhere, he expressed admiration for the noble character of the converted but admitted his “‘great difficulty has been in getting a sense of my sinfulness’” (qtd. in Habegger, Wars, 243). He managed to overcome his resistance to orthodox expectations just enough to join the church as Susan urged. By 1870 his dearest friend, Rev. Jonathan Jenkins, minister of First Church, described Austin as “‘not an atheist or freethinker . . . but only about fifty years in advance of his generation’s views’” (qtd. in Bianchi, Face to Face, 133).

Figure 18. Austin Dickinson. Photographic portrait, ca. 1869, by Richard Hurley. Special Collections, Brown University Library.

Martha Dickinson Bianchi recalled that neither of her parents wanted their children to experience the oppression of “the more Puritan Sunday of their own youth” (Bianchi, “Life Before Last,” 27). When a conscientious young Sunday School teacher offered too lurid a description of the “lake of burning brimstone awaiting us all,” Austin’s prompt response was to “wipe out hell and Sunday-school with one burst of indignation” (Bianchi, “Life Before Last,” 26). His patience with Congregational theology ran out after Jenkins left Amherst in 1877 to accept a call in Pittsfield, Massachusetts. Austin “brought home all our hymn books and wouldn’t go to church anymore” (Bianchi, “Life Before Last,” 92). Jenkins’ departure provoked a controversy between Austin and the church elders about “the delinquencies of his individual interpretation of belief.” The deacon delegated to remonstrate with Austin met only with an amused brush-off: “Excommunicate away, Deacon! That’s all right. Bear you no ill-will. I’ll bid you good morning!” (Bianchi, Face to Face, 134). Ten years later, Austin began a long affair with Mabel Loomis Todd, which put the two squarely at odds with the moral teachings of the church, but both remained active parishioners. Austin contributed liberally to the church treasury, remained a pillar of the Parish Committee, and oversaw construction of the new meetinghouse directly across the street from The Evergreens. Church leaders turned to Austin for an address on “Representative Men of the Parish, Church Buildings and Finances” to celebrate the church’s 150th anniversary (fig. 19). Austin’s community stature—and his pocketbook—encouraged clergy and parishioners alike to overlook his heterodox religious opinions.

Figure 19. Title page, A Historical Review. One Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary. First Church of Christ. Amherst, Massachusetts. November 7, 1889. Amherst: Press of the Amherst Record, 1890. New York Public Library via Internet Archive.

Figure 20. First Church of Christ (Congregational), built 1867. From A Historical Review. One Hundred and Fiftieth Anniversary. First Church of Christ. Amherst, Massachusetts. November 7, 1889. Amherst: Press of the Amherst Record, 1890. New York Public Library via Internet Archive.

Although less is known about Lavinia’s religious views, it appears that she did not struggle as vigorously to find a personally satisfactory theology as did her brother and sister. She responded readily to the 1850 revivals by exhorting her brother and sister to become Christians early in the year and by joining the church herself in November.[5] Lavinia was subsequently an active participant in church activities and among intimates always prepared to render an opinion—and use her gift for mimicry—on the sermon, services, or fellow parishioners. An obituary in the Springfield Republican noted that Lavinia was “very reticent” about her own religious experiences and sympathies.

She often questioned the dealings of Providence, and sometimes seemed defiant in the presence of some cruel bereavement. But for all this, I do not believe that her faith in an all-wise, benevolent Being ever suffered more than momentary eclipse. She was not given to analyzing her spiritual condition. She seemed less conscious of her duties toward her Creator than toward the creatures of his hand.[6]

Martha Dickinson Bianchi remembered her aunt Lavinia as a realist with a thoroughgoing “dread of cant and all conventional religious conversation” (Bianchi, “Life Before Last,” 291). She “wasted little time” upon spiritual matters except—in keeping with a general family characteristic—as it was reflected through Nature (Bianchi, “Life Before Last,” 290).

A vast but still inconclusive literature attempts to explain Emily Dickinson’s religious and spiritual platform.[7] It is not within the scope of this essay to distill that literature or to draw new interpretations, but rather to remind us that our interest in the family libraries serves the purpose of developing a more informed context for Dickinson’s spiritual explorations. Because she experienced profound and conscientious religious doubts as a teenager, went through an existential crisis of unknown origin as a young adult, exercised detailed knowledge of the Bible, encountered a ferment of contemporary religious thought, withdrew from her ecclesiastical tradition, and expressed her relationship to spiritual matters in poetic form even as that relationship changed, it has been difficult for scholars and readers to stabilize that religious platform.

In her elegant obituary of Emily, even Susan Dickinson had difficulty defining (or, perhaps, protecting) her friend’s religious mind, but she linked it implicitly with a bare-bones library.

Keen and eclectic in her literary tastes, she sifted libraries to Shakespeare and Browning —quick as lightning in her intuitions, and analyses, she seized the kernel instantly, almost impatient of the fewest words by which she must make her revelation. To her life was rich, and all aglow with God and immortality. With no creed, no formulated faith, hardly knowing the names of dogmas she walked this life with the gentleness and reverence of old saints, with the firm step of martyrs who sing while they suffer. (S. Dickinson, 268)

The absence of a straightforward statement of her beliefs makes it all the more difficult to square the circle—or circumference—of Dickinson’s spiritual journey and identity. As was her habit, Dickinson framed this process of spiritual formation in poetic form:

The Props assist the House

Until the House is built

And then the Props withdraw

And adequate, erect,

The House support itself

And cease to recollect

The Augur and the Carpenter –

Just such a retrospect

Hath the perfected Life –

A Past of Plank and Nail

And slowness – then the scaffolds drop

Affirming it a Soul –

(Fr729b)

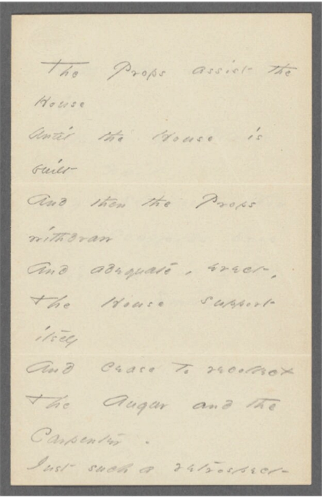

Figure 21. Emily Dickinson, “The Props assist the house” (Fr729b). Poems: Loose sheets. The Props assist the House. MS Am 1118.3 (347). Houghton Library, Harvard University. From the Emily Dickinson Archive.

In perfect metaphor, Dickinson portrays the individual being as a “House” whose construction is ultimately completed or “perfected,” through Jesus Christ “the Carpenter,” as a fully endowed and unimpeded “Soul.” Even in such straightforward poetic form, Dickinson conveys a far more complex theology than some of her more familiar poems imply:

Some keep the Sabbath going to Church –

I keep it, staying at Home –

With a Bobolink for a Chorister –

And an Orchard, for a Dome –

(Fr236)

With its brisk, lighthearted mood and plain references to the natural world that are immediately recognizable to the reader, this poem has become one of Dickinson’s most memorable verses. Its flippant tone concerning mainstream religious observance, however, has reinforced popular perceptions of Dickinson’s attention to religion as less that serious. In these two examples, it is clear that Dickinson’s tone and sense of gravity concerning religious experience varies tremendously. Some poems embrace the need for faith:

Faith - is the Pierless Bridge

Supporting what We see

Unto the Scene that We do not -

Too slender for the eye(Fr978)

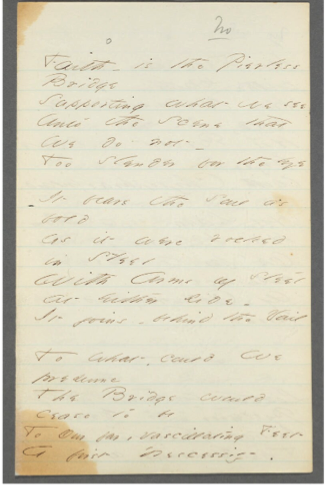

Figure 22. Emily Dickinson, “Faith - is the Pierless Bridge” (Fr978a). Poems: Packet XXXIII (mixed sets). Includes 26 poems, written in ink, dated ca. 1862-1864. Houghton Library, Harvard University. From the Emily Dickinson Archive.

Others are plainly and comically irreverent:

The Bible is an antique Volume -

Written by faded Men

At the suggestion of Holy Spectres –

(Fr1577)

Sometimes Dickinson rails at God’s distance:

Of Course - I prayed -

And did God Care?

He cared as much as on the Air

A Bird - had stamped her foot -

And cried “Give Me” -

(Fr581)

Even more startling than her anger is Dickinson’s disgust at the notion that humankind’s capacity for faith is a prop for a powerless God.

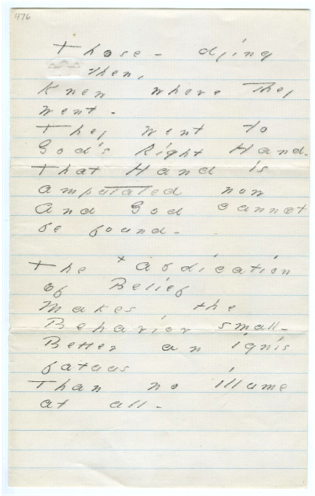

Those - dying then,

Knew where they went -

They went to God’s Right Hand -

That Hand is amputated now

And God cannot be found -

(Fr1581)

Figure 23. Emily Dickinson, “Those - dying then” (Fr1581).* Amherst Manuscript #476. Amherst College. From the Emily Dickinson Archive.*

A substantial bibliography traces Emily Dickinson’s wary stance toward orthodox religious beliefs and practices during her lifetime. The few poems noted above illustrate the myriad ways in which Emily Dickinson resisted and grappled with conventional religious culture in the second half of the nineteenth century and in the second half of her life. She cultivated a close familiarity with biblical texts and regularly deployed those texts in poetry and correspondence, sometimes accepting their import at face value, at other times insinuating new meanings. At her most extravagant, Dickinson pushed her use of the scriptures over the normative edge, perhaps abetted by the contents of the books on the shelves of the family libraries.

A principal recipient and interpreter of Dickinson’s biblical allusions in poems and letters was her sister-in-law Susan Gilbert Dickinson. The two handed back and forth texts by religious philosophers and exchanged views about spiritual concerns. Susan joined the congregational First Church in Amherst on the very same day as her future father-in-law Edward Dickinson and, as we have seen, considered commitment to Christ a sine qua non for her marriage to Austin. Yet, Susan introduced at least a few unconventional elements—from the trivial to the momentous—into the Dickinson family. As a newlywed, for example, she raised the neighbors’ eyebrows as well as suspicions of Romanism when she brought the New York Knickerbocker tradition of hanging Christmas wreaths at the windows of The Evergreens.[8]

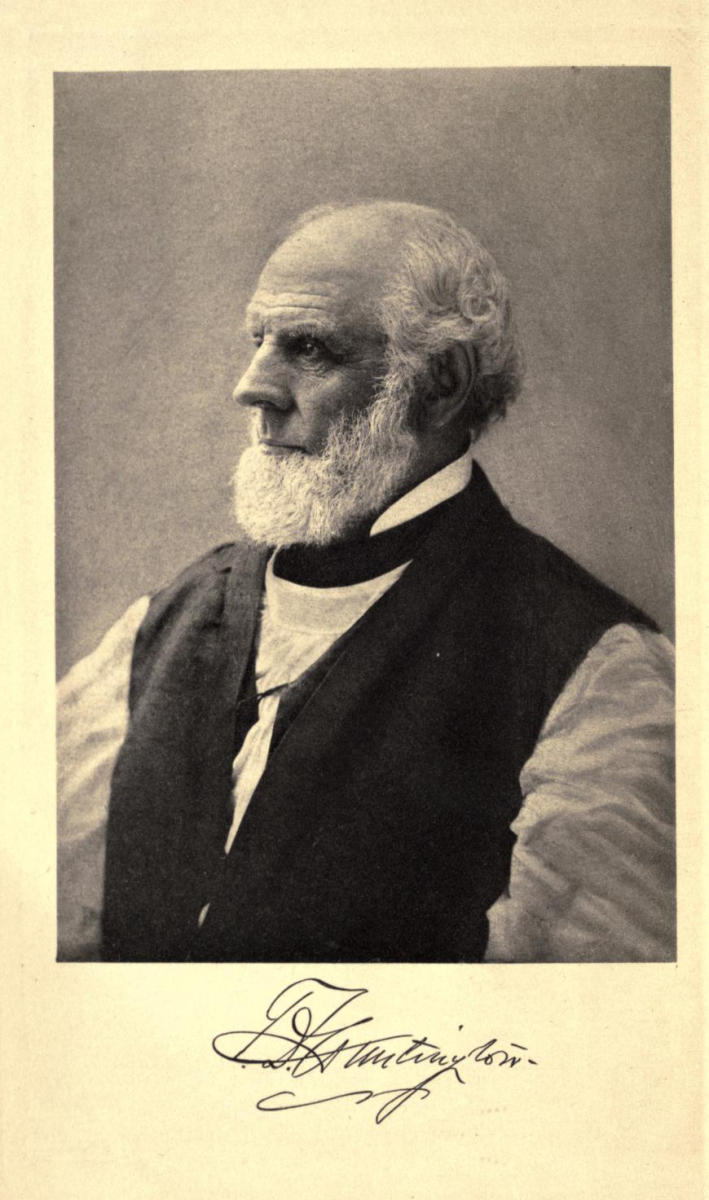

More significantly, Susan became known for evenings of cultural and intellectual interchange at The Evergreens where statesmen and legislators, ministers, philosophers, and scientists discussed contemporary topics of all kinds, including religion. Amherst College professor Elihu Root used the occasion of a supper party at The Evergreens to introduce “the daring theory of Evolution,” aided by Professor Benjamin Kendall Emerson, proudly declaring himself a “Theistic Evolutionist,” and Maria Whitney, “all but excommunicated from the Jonathan Edwards church in Northampton for her scientific free-thinking acquired in Germany” (Bianchi, “Life Before Last,” 103). Susan was also active during the 1880s in working with poor children and families in Logtown, east of Amherst, providing food, clothes, literacy instruction, and Sunday School lessons. Her work with clergy and families at Dwight Chapel grew out of the beginnings of a social gospel movement championed by leaders such as Horace Bushnell, Henry Ward Beecher, and Frederic Dan Huntington, men who visited The Evergreens and whose works appeared on the Dickinson library shelves.

Some Dickinson biographers have taken a jaundiced view of Susan Dickinson’s religious beliefs, observing, with implications of hypocrisy, that she was “never famous for her piety” (Sewall, Life, 100), that she “sporadically insisted on certain orthodox prohibitions” (Habegger, Wars, 266), or that her charitable work carried the trappings of “missionary zeal” (Habegger, Wars, 619). Perhaps the documented tensions between Austin and Susan over his conversion, or disproportionate reliance on Mabel Loomis Todd’s writings for biographical information about Susan, have allowed this skepticism to go relatively unchecked. A more in-depth biography of Susan Dickinson may offer a less idiosyncratic understanding of her personality and beliefs.[9]

“Those — dying then, / Knew where they went —”: Annihilation and Its Discontents

While Emily documented her spiritual struggle in poetic form, Susan Dickinson documented hers in her library. Of the roughly 200 religious texts on the shelves at the Homestead and Evergreens, easily a third can be linked to Susan, and about a quarter can be linked to Edward Dickinson (fig. 23).

Figure 24. Primary connection of religious titles in the family libraries to Dickinson family members.

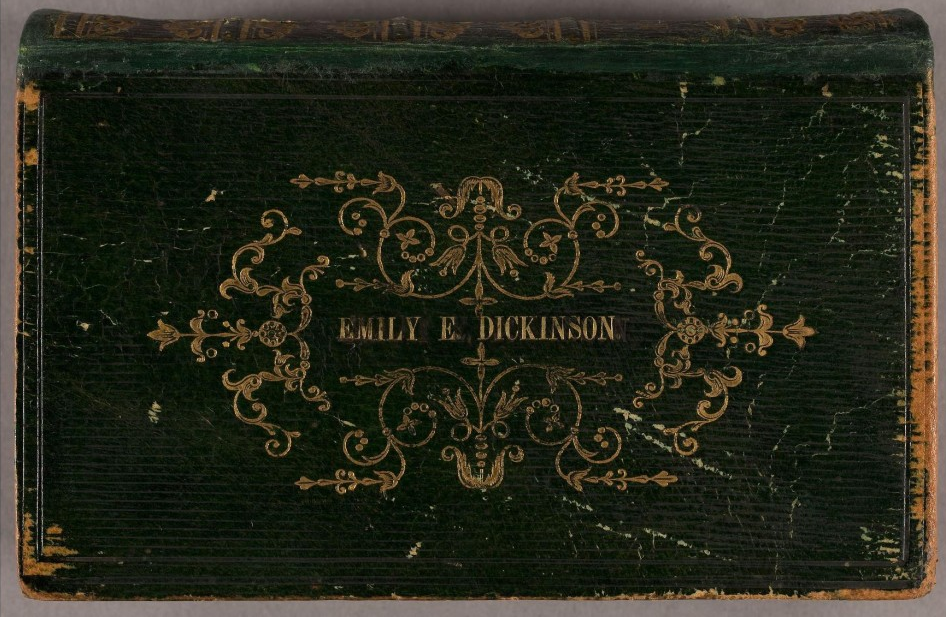

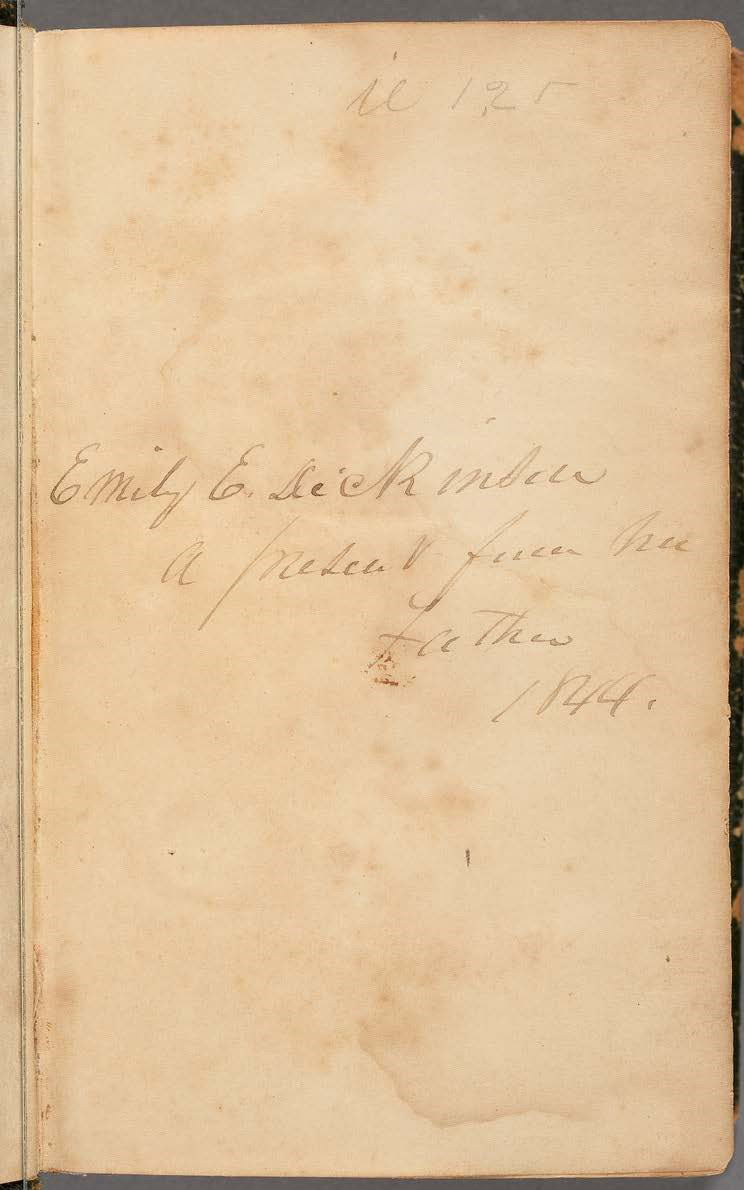

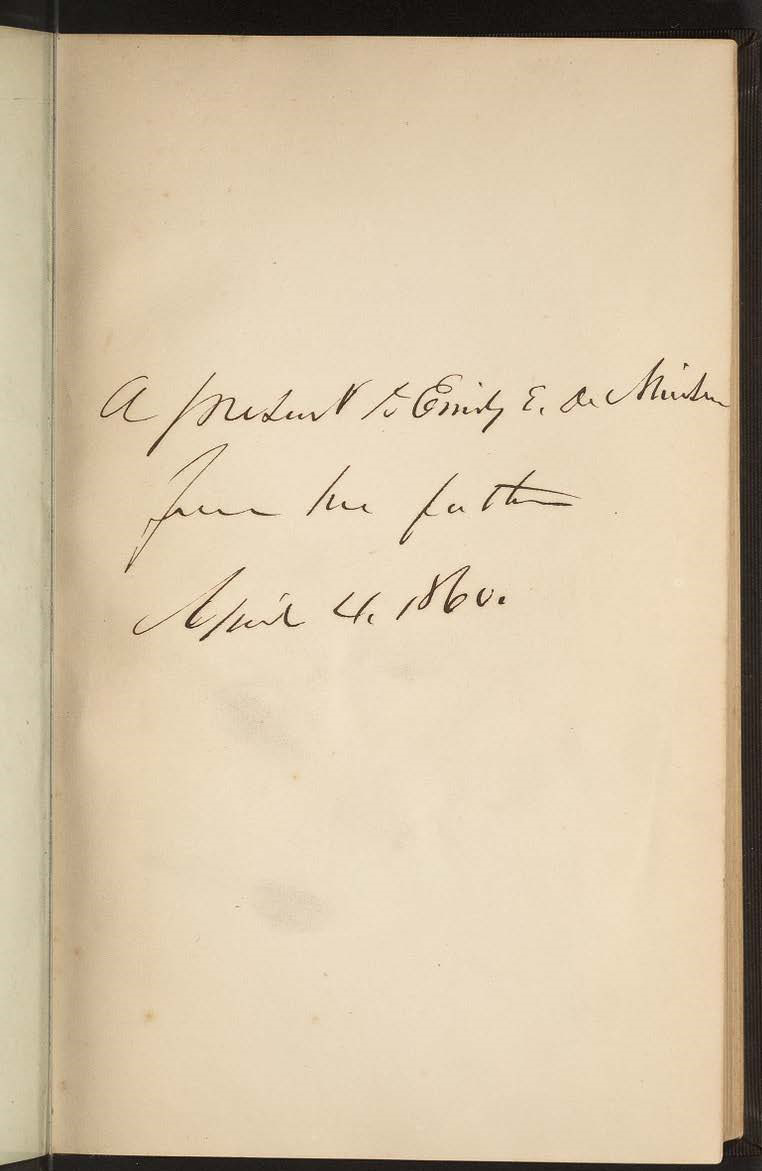

Given Emily Dickinson’s engagement with spiritual themes in her poetry and letters, it is surprising that only a handful of these books can be specifically identified by inscription with her: a couple of Bibles, a school textbook on ecclesiastical history, Emerson’s transcendentalist essays, and a few others. When Emily claimed “my father buys me many books, but begs me not to read them,” she probably was not referring to religious texts (L 261, 2:404-05). Inventories show that Edward gave his poet daughter just four titles in this genre. He presented to her at age thirteen, as he did to each of his three children, the King James version of the Bible (figs. 25-26). It was the text to which Dickinson turned again and again in prose and poetry for references to biblical persons, stories, epigrams, and texts.

Figures 25 and 26. Cover and inscription, “Emily E Dickinson, a present from her father, 1844.” The Holy Bible. Philadelphia, 1843. Dickinson family library, EDR 8. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

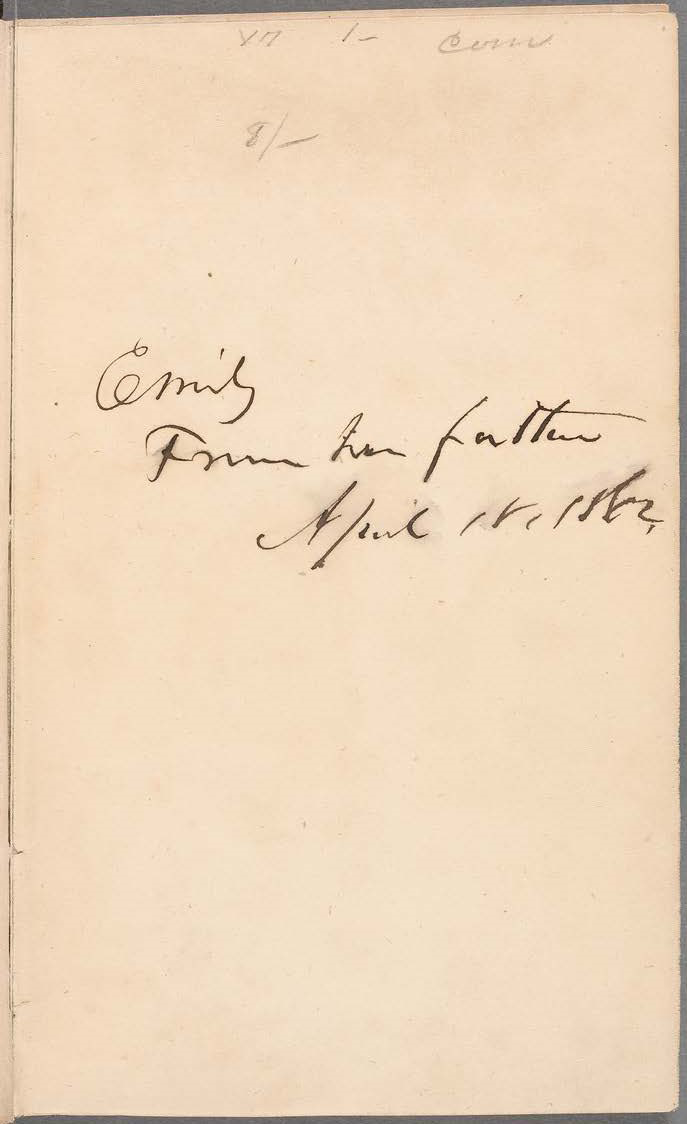

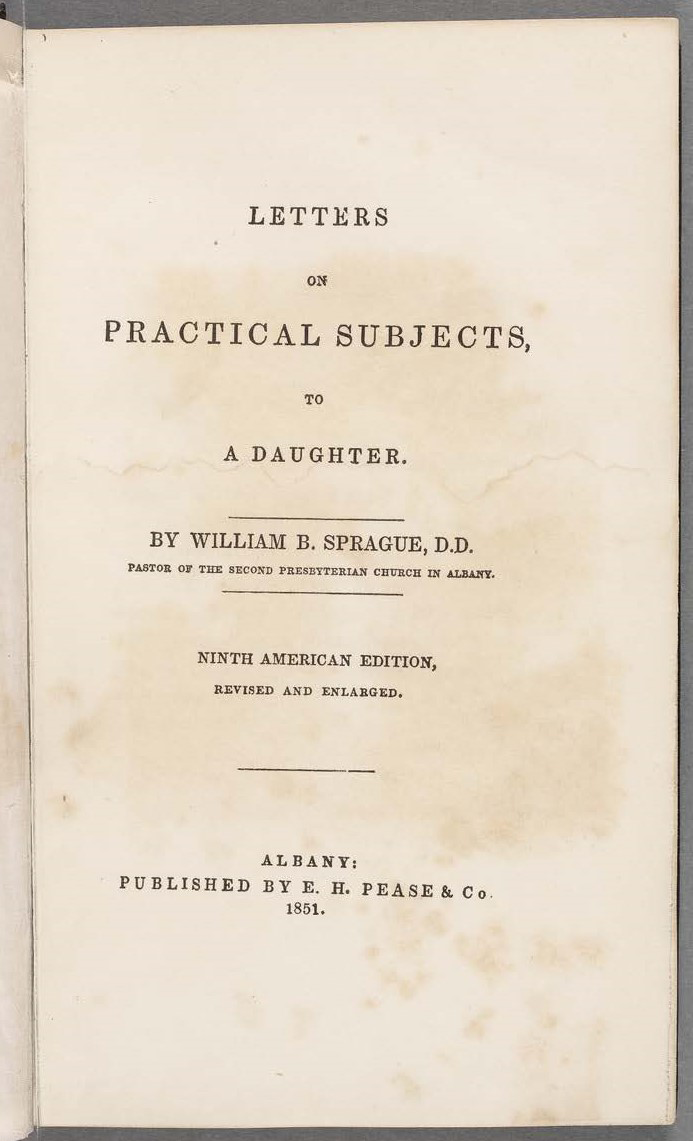

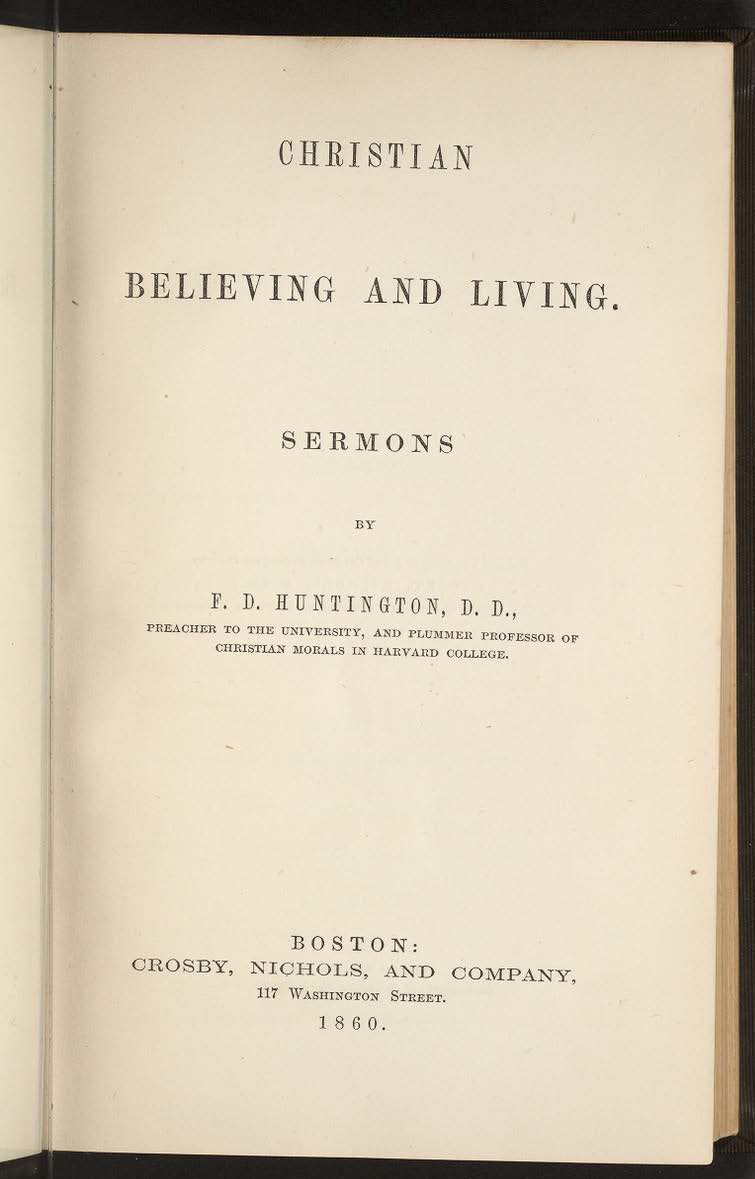

A second volume Dickinson received from her father was Christian Believing and Living, sermons by family friend Frederic Dan Huntington. Born into a family of Congregational clergymen turned Unitarian, Huntington was a specially valued friend of Susan Dickinson. The third religious text inscribed to Emily from her father (April 18, 1862) was William Buell Sprague’s Letters on Practical Subjects, published in 1851 (fig. 27-28). The last paternal gift, made just before Edward’s death in 1874, was The Life of Theodore Parker, by Octavius Brooks Frothingham. With her father’s death too painfully recent, Dickinson offered the book to her literary preceptor Thomas Wentworth Higginson a year later. Her first encounter with the writings of the Unitarian transcendentalist and abolitionist Parker came in 1859 when Mary Bowles sent her The Two Christmas Celebrations as a holiday present. “I never read before what Mr. Parker wrote. I heard that he was ‘poison’. Then I like poison very well,” Dickinson wrote with obvious relish. She wasn’t the only one: “Austin stayed from service yesterday afternoon, and I, calling upon him, found him reading my Christmas gift” (L 213, 2:358-59). An example of Parker’s “poison” is his statement, “I believe that Jesus Christ taught eternal torment—I do not accept it on his authority” (Parker, from “Two Sermons,” qtd. in Bartlett, 15n). In light of such heresy, the fact that Edward Dickinson gave his daughter a gift that would appeal to her theological interests, no matter his own views, seems a clear indication that he was not as doctrinaire as might be assumed.

Figures 27 and 28. Inscription, “Emily from her father, April 18, 1862,” and title page. Letters on Practical Subjects to a Daughter. Albany, 1851. Dickinson family library, EDR 528. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

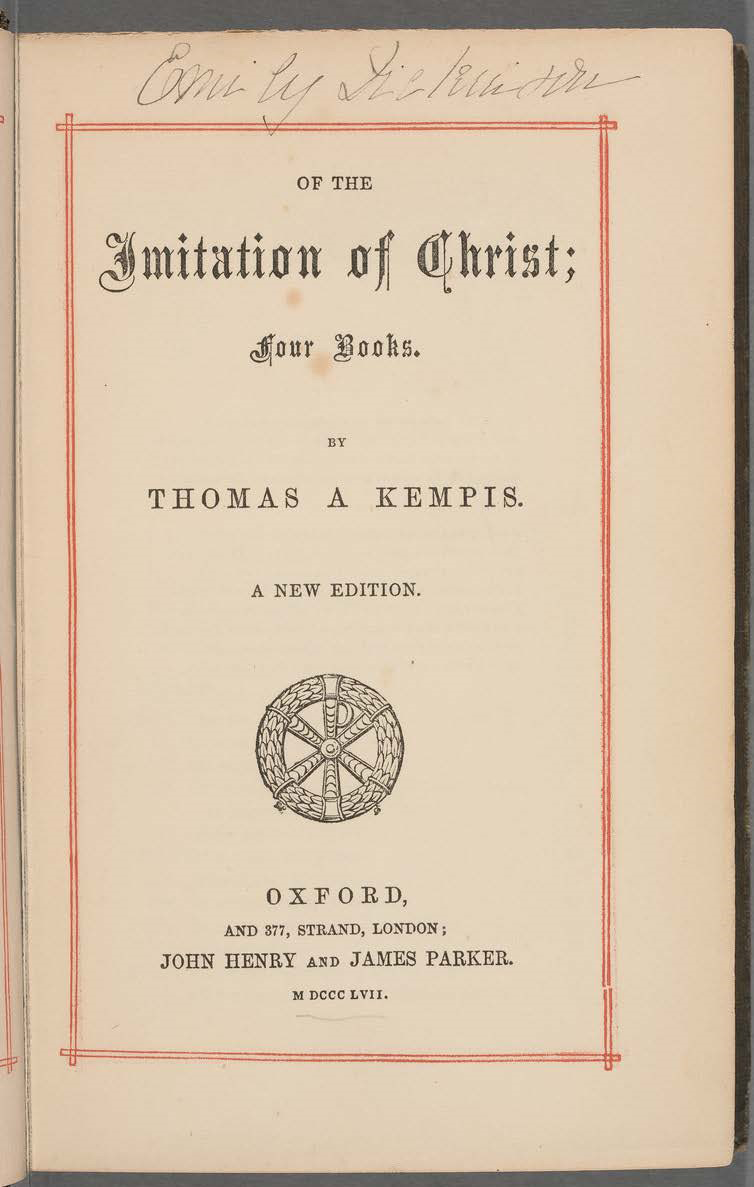

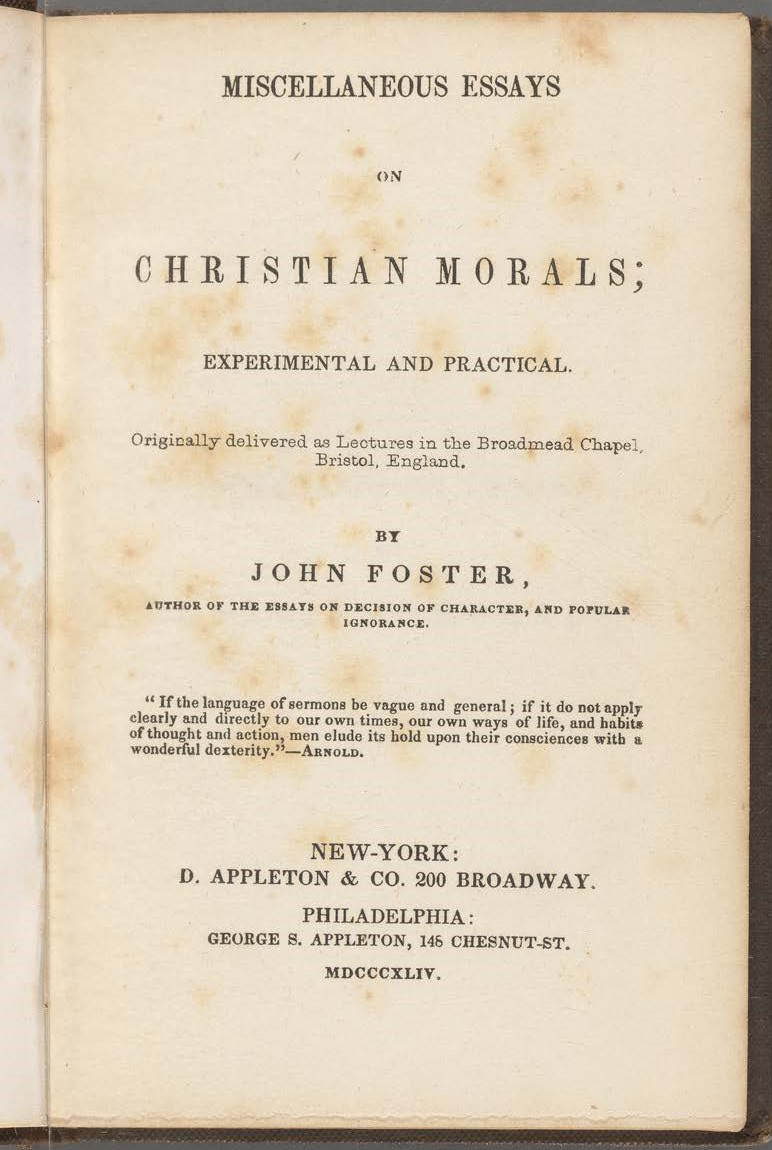

Two additional texts Emily owned that are significant and suggestive of her struggles with faith are Thomas a Kempis’ Of the Imitation of Christ, a gift from Susan, which she kept in her bedroom (fig. 29), and John Foster’s Miscellaneous Essays on Christian Morals; Experimental and Practical (fig. 30).

Figure 29. Title page. Thomas à Kempis, Of the Imitation of Christ. Oxford, 1857. Dickinson family library, EDR 529. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Figure 30. Title page. John Foster, Miscellaneous Essays on Christian Morals. New York; Philadelphia, 1844. Dickinson family library, EDR 136. Houghton Library, Harvard University.

Also on the shelves at The Evergreens was a book entitled Life and Death Eternal: A Refutation of the Theory of Annihilation, by Samuel C. Bartlett, Professor of Theology at Chicago Theological Seminary and future President of Dartmouth College (figs. 31-32). Life and Death Eternal is, as the title makes clear, a strenuous counter-attack on an infectious doctrine gaining adherents in the mid-nineteenth century that “the Bible does not teach that the destiny of the wicked is endless suffering,” but rather the complete and total end—that is, “Annihilation”—of the soul as well as the physical body. Bartlett identified two variations on the theory of annihilation: first, the suffering of wicked souls for a period before their complete “restoration to holiness and happiness”; second, Universalism, with its contention that there shall be “no punishment at all hereafter” for wicked or righteous souls but rather immediate entry at death “into a state of happiness” (Bartlett, 15-17).

Figures 31 and 32. Title page and table of contents. Samuel C. Bartlett, Life and Death Eternal: A Refutation of the Theory of Annihilation. Boston, 1866. New York Public Library via Internet Archive.

In 1852, when Emily Dickinson was twenty-one years old, her father interviewed Bartlett, a promising young minister just returned from the Western Reserve, as a candidate for the pastorate of Amherst’s First Church. Bartlett and his wife were obliquely related through marriage to Susan Huntington Gilbert, soon to be engaged to Austin Dickinson. Nothing came of the interview with Edward Dickinson, but the following year Susan began brief but close friendship with the Bartletts, even asking Samuel to officiate at her wedding. Nothing came of that invitation, either, when Susan subsequently insisted on being married at her aunt’s house in Geneva, New York.[10]

These personal acquaintanceships are not insignificant for understanding how Bartlett’s treatise ended up on Dickinson family bookshelves. But what, if anything, did this “Refutation” mean to Emily Dickinson, who had nearly sixteen hundred other books in her own family libraries to choose from? How did it fit into the denominational views and religious climate of her home, her town, and her reading? A closer look at Bartlett’s controversy may help to answer these questions—especially since John Foster, author of Miscellaneous Essays on Christian Morals, another book on her shelves, was one of the protagonists.

Foster was an English Baptist minister active early in the nineteenth century who published an open letter rejecting the doctrine of eternal punishment; however, he would not commit himself as to whether wicked souls would be fully annihilated or fully and immortally restored to God. His letter spurred a resurgence of annihilationist thought in the mid-nineteenth century, which exasperated more orthodox thinkers such as Samuel Bartlett. Despite the clarity of the scriptures in support of the doctrine of eternal punishment, Foster was aghast at the implication that God had stacked the deck against the redemption of humankind. Under this doctrine,

“how inconceivably mysterious and awful is the whole economy of this human world! The immensely greater number of the race hitherto, through all ages and regions, passing a short life, under no illuminating, transforming influence of their Creator . . . in a state unfit for a spiritual, happy, and heavenly kingdom elsewhere, —and all destined to everlasting misery. The thoughtful spirit has a question silently suggested to it of a far more emphatic import than that of him who exclaimed, ‘Hast thou made all men in vain?’ To see a nature created in purity, ruined at the very origin, the grand remedial visitation, Christianity, laboring in a difficult progress; soon perverted; . . . its progress distanced by the increase of the population; thousands every day passing out of the world in no state of fitness for a pure and happy state elsewhere, — oh, it is a most confounding and appalling contemplation!” (qtd. in Bartlett, 140-142)

What was God thinking? Foster wondered. The language is remarkably similar to Austin Dickinson’s youthful outburst to Martha Gilbert quoted above and, at its core, expresses the same theological question Dickinson doggedly pursued in life and in poetry.

Of God we ask one favor, that we may be forgiven –

For what, he is presumed to know –

The Crime, from us, is hidden –

Immured the whole of Life

Within a magic Prison

We reprimand the Happiness

That too competes with Heaven

(Fr1675)

Figure 33. Emily Dickinson, page from letter to Helen (Hunt) Jackson (L 867B, not in Letters) with “Of God we ask one favor” (Fr1675). Amherst Manuscript #817. Amherst College. From the Emily Dickinson Archive.

Eternal punishment and the doctrine of pre-destination went hand in hand. But the Puritanism of Emily Dickinson’s time flagged in the face of natural theology, Darwinism, and the incomprehensible loss of life brought by the Civil War. Theologians, ministers in the pulpit, those in church pews and those who had deserted the pews wrestled with the twin problems of a just God and human suffering. Annihilation and its “Refutation” was one strand of interpretation attempting to address these problems and intersected with what Dickinson called her “flood subject,” immortality. What confidence can human beings have in the promise of salvation? Or, for that matter, in God? What had humankind done to merit eternal punishment in hell, if such existed, in the first place? Our understanding of religious influences on Dickinson’s views and poetry can be expanded by recognizing that she could pluck this book off the shelf of her brother’s library, that her family knew the author, and that it posed an answer to a question she was constantly turning over in her mind.[11]

“Protestants dressing up religion”: From Unitarianism to Anglicanism

The spiritual biography of family friend Rev. Frederic Dan Huntington, author of Christian Believing and Living, was no doubt intriguing to Emily Dickinson (figs. 34-36). After graduating from Amherst College, he began his ministry as the Unitarian pastor of South Church of Boston, became professor of Christian Morals at Harvard and preacher to the University, but in 1860, resigned his professorship, left Unitarianism behind, was ordained an Episcopal priest, and became founding minister of Emmanuel Episcopal Church in Boston. Nine years later, Huntington was elected the first Episcopal bishop of the diocese of Central New York, a post he held for thirty-five years.

Figure 34. Rt. Rev. Frederic Dan Huntington, ca. 1900,hotographer unknown. From Arria S. Huntington, Memoir and Letters of Frederic Dan Huntington, First Bishop of Central New York. Boston and New York, 1906. Trinity College Library, University of Toronto, via Internet Archive.

Figures 35 and 36. Inscription, “A present to Emily E. Dickinson from her father, April 4, 1860, and title page. Frederic Dan Huntington, Christian Believing and Living: Sermons. Boston, 1860. Dickinson family library, EDR 1-590, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

The fluidity of his religious affiliations was notable at the time, and the Dickinson family was interested eyewitness to its progress. An explanation of Huntington’s denominational shift appeared in his 1904 obituary:

He was bred in that transition from puritan Congregationalism to Unitarianism, wherein human reason was almost deified, found it impious and impossible to prostrate his intellect before any authority which the Bible, earliest traditions and the scrupulous conscience could not clearly make out as unmistakably divine. . . . Unitarianism at first was congenial to the natural virility of his intellect, but it failed to satisfy his deepening and widening conception of a supernatural order, revealed and guaranteed in the incarnation, and historically perpetuated in the visible organic kingdom of Christ. At the proper place . . . he made an irrevocable decision between the Christian Gospel historically revealed and permanently declared and settled in Christ and a Christian Gospel, perpetually revising itself in the consciousness of the ages. (Maxon, 481)

A founder of the Episcopal parish in Amherst, Huntington was, for Sue, a trusted friend and spiritual advisor who appreciated her “philosophical” tendencies.[12] Especially after her son Ned’s death in 1898, when she found herself yearning for more than dull Congregationalism could offer, Susan sought Huntington’s counsel about her attraction to Roman Catholic forms of worship. Like other well-educated Protestant women, she found the beauty of higher church liturgical traditions and community of saints not bound by time or space strongly appealing. Harriet Beecher Stowe, for example, wrote extensively and sympathetically in her later works of fiction about a sacramental feminized theology of love that discarded austere Calvinism and its obsessive search for evidences of conversion. The doctrinal moderation of the Episcopal Church satisfied Stowe’s desire for liturgical aesthetics and flexible ecumenism, and she was eventually received into the Episcopal Church.[13] The influence of Huntington and Stowe on Susan Dickinson was personal and direct: the Dickinsons exchanged many visits with the Huntingtons in neighboring Hadley (fig. 37), and Stowe was a guest at The Evergreens when visiting her daughter Georgianna and son-in-law Rev. Henry F. Allen, rector of Grace Episcopal Church in Amherst from 1872 to 1877.

Figure 37. Forty Acres, the Huntington family home, ca. 1900, photographer unknown. From Arria S. Huntington, Memoir and Letters of Frederic Dan Huntington, First Bishop of Central New York. Boston and New York, 1906. Trinity College Library, University of Toronto, via Internet Archive.

Bishop Huntington’s response to Susan’s 1898 query was a full expression of the basics of his Christian faith: the incarnation as the “one vital theme of all the Scriptures”; a “society” of believers who strive to cultivate the strength of “character” worthy of Christ’s presence among humankind; “Common worship, Creed, Sacraments, and Ministry.” The difficulty of institutional Christianity, Huntington went on, is that “Men must manage it. They will modify & color & shape it according to their own shifting & erring ideas. They will add to it, & take from it. The variations & imperfections & abuses are unavoidable, unless we imagine an unceasing miracle. It is superficial to blame the church for the follies, extravagances, bigotries, narrowness, of its mismanagers” (Huntington 1898). Despite these historic failings, Huntington insisted, the church has never sundered “the grand historical chain that links us with the Apostles” (Huntington 1898). An advocate of ecumenism as well as the truth of the incarnation, Huntington’s views stopped short of advising Susan to affiliate with one denomination or another.

Austin’s relationship with Huntington was more complicated. Austin, the College treasurer, and Huntington, a long-time trustee, communicated frequently about College business. When it came to religious affairs, and despite his so-called heterodoxy, Austin had no patience with “Protestants dressing up religion.” He respected both Protestants and Catholics, his daughter said, “but Episcopalians were neither, and variations were uncalled for.” On social occasions, Austin argued with the Bishop about liturgical differences until both dropped the subject “after reason failed to supply a bridge” between them (Bianchi, “Life Before Last,” 113).

Huntington also came to know Emily Dickinson through his visits to Austin and Susan in the 1860s. He later wrote that “she gave me her confidence and made herself my friend, tho’ afterwards I scarcely saw her. The image that comes before me when I think of her is hardly more terrestrial than celestial—a Spirit with only as much of the mortal investiture as served to maintain her relations with this present world” (Leyda, 2:479). But what impression did he make on her? Huntington published Christian Believing and Living in 1859 as a declaration of beliefs that had moved decisively toward what contemporaries considered the conservative end of the spectrum of Protestant theology, from Unitarianism to Anglicanism. Edward Dickinson’s views most likely fell at the mid-point of this spectrum, but those of his daughter Emily seemed somehow to encompass the entire range. The purpose of Edward’s gift of this volume to Emily (April 4, 1860) may have been to find common ground between father and daughter on the essentials of Christian practice when the possibility of agreement on theological orthodoxy seemed remote.

Future Directions

Emily Dickinson did not frame her poetic discussion of her “Flood subject” without reference to the currents of contemporary theology. Her family’s prominence in civic affairs as well as the growth of Amherst College exposed her on a personal level to many of the leading religious thinkers of the day, including Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry Ward Beecher, Frederic Dan Huntington. Her father’s collection of religious books was heavily grounded in his own rationalist education and outlook, but she shared with her brother, sister, and sister-in-law (as well as with other correspondents that must go unmentioned in this brief article) a generational restlessness with orthodox Congregationalism and a willingness to ride new currents of theological interpretation in the second half of the nineteenth century.

We can now see, as Emily did, that the family libraries at her disposal were eclectic in content and doctrine, reflective of contemporary theological trends and of openness to progressive interpretations of scripture. Although the books on the shelves cannot fully explain Emily Dickinson’s controversy with faith and with God, Samuel Bartlett’s Refutation, Frederic Dan Huntington’s Christian Believing and Living, and other texts owned and shared by Dickinson family members demonstrate their possibilities as essential and rewarding resources for charting the theological course she set for herself. Scholars have hitherto tended to look at books and their influence on Dickinson either as discrete texts (Shakespeare, the Bible) or as distinct genres (textbooks, novels, nineteenth-century women writers) that attracted Dickinson’s personal attention, the traces of which we can see in her work in part because these are the texts and genres that matter to us. Using the example of religious texts within the family library—a set of materials eminently available to her, which served an abiding concern she shared with the other members of her household—this essay suggests that there may be much to learn from considering the construction of the family libraries as an ensemble of influences on the poet and her family in a variety of genres, assembled in active ongoing exchange with contemporary ideas, across several decades. Reconstructing the individual interests, patterns of acquisition, ownership, gifting, and consumption of texts in the two Dickinson family libraries offers ample opportunity for expanding and redefining our understanding of Emily Dickinson’s literary milieu and the ways that reading shaped her.

Although Emily herself may not have valued exclusive personal ownership, she considered books essential to her intellectual existence. Consequently, conveying the contours of Dickinson’s life at her home is impossible without representing the books so critical to her intellectual formation. To that end, the Emily Dickinson Museum maintains an ongoing effort, “Replenishing the Shelves,” to re-create the libraries at the Homestead and Evergreens based on detailed inventories of the books transferred to Brown and Harvard universities. A list of books actively sought and already acquired can be found at www.EmilyDickinsonMuseum.org/books.

Notes

[1] The quotation in the title comes from Emily Dickinson’s letter to F. B. Sanborn, about 1873 (Letters, #402, 2:516). Subsequent references to this edition will be cited parenthetically by letter number, volume, and page. Poems will be cited parenthetically by the number assigned to them in Poems, ed. Franklin.

Quotations in the subtitles to follow come from these sources: “They… address an eclipse” (L 261, 2:404-05); “This then is a book!” (Higginson, letter to Mary Higginson, L 342b, 2:475); “household of faith” (Galatians 6:10); “Those—dying then, / Knew where they went—” (Dickinson Fr1581); “Protestants dressing up religion” (Bianchi, “Life Before Last,” 113).

[2] See Capps; Habegger, “Glimpse”; Heginbotham, “Reading Dickinson” and “Reading in the Dickinson Libaries”; Lowenberg; Sewall, Life, especially chapter 28, “Books and Reading,” 668-705; and Stonum.

[3] This essay emphasizes family or household libraries as material culture collections within a social context. Reading in the home has received limited direct attention from social historians. See, for example, Clark, who touches on the place of bookcases within the home, and Nylander, 107, 112, 225. For later time periods, see Heininger and Kruger.

[4] Since Mary Landis Hampson’s bequest of books and papers to the John Hay Library for Special Collections at Brown University, the finding aid for Bianchi manuscripts has been expanded gradually. See “Guide to the Martha Dickinson Bianchi papers.” The 2,700 books have not yet been fully catalogued.

[5] Lavinia’s hortatory letters to Austin are reprinted in Bingham, 90-97.

[6] The Springfield Republican published Joseph K. Chickering’s editorial letter, “The Late Lavinia Dickinson,” on November 30, 1899. It is reprinted in Bingham, 490-91.

[7] For examples of various approaches to Emily Dickinson and religion, see Brantley; Burbick; Crumbley; Eberwein; Freedman; Gilliland; Hughes; Keane; Lundin; McIntosh; Mayer, “‘The Back Story’” and “God’s Place”; and Morgan.

[8] “Apparently, his heterodoxy was a real obstacle in his early relations with Sue; [Austin], a Dickinson, had to plead with her not to dismiss him as an atheist” (Sewall, 237). The anecdote about laurel wreaths appears in Bianchi, Life and Letters, 13.

[9] A biography of Susan Dickinson by Martha Nell Smith is anticipated in the near future.

[10] For a full account of Susan Huntington Gilbert’s relationship with Samuel Bartlett, see Longsworth, 67-110. Longsworth suggests that Susan was romantically attracted to Bartlett during her engagement to Austin Dickinson.

[11] For explorations of the problem of suffering and the problem of a just God in Dickinson’s thought and poetry, see Keane, Mayer, and, especially, McIntosh.

[12] “I suppose Susan, who writes philosophical letters, loves philosophy—” (Huntington, Letter to Susan Huntington Dickinson, n.d.).

[13] “An important difference between the two [Congregational and Episcopal] church traditions can be seen in the Anglican catechism’s less restrictive standards for full church membership—and, by implication, its suppositions about who might belong to the invisible Kingdom of God. Whereas the tradition developed by New England Puritans sustained the expectation that authentic believers must claim some specific temporal experience of regeneration or ‘effectual calling,’ the Book of Common Prayer’s catechism and liturgy emphasized rather one’s need to adhere faithfully to the church's beliefs, prayers, sacraments, and moral standards as summarized in the Decalogue. Ordinarily one expected the ‘new birth into righteousness’ affirmed in the Book of Common Prayer catechism to be effected not by an adult experience of regeneration so much as by sacramental baptism” (Gatta, 415). See also Goluboff.

Works Cited

Bartlett, Samuel C. Life and Death Eternal: A Refutation of the Theory of Annihilation. Boston: American Tract Society, 1866.

Bianchi, Martha Dickinson. Emily Dickinson Face to Face. The Riverside Press, 1932.

-----. [Family Books.] Martha Dickinson Bianchi papers, MS 2010.046. Special Collections, Brown University Library, Providence RI.

-----. “Life Before Last: Reminiscences of a Country Girl.” Edited by Barton St. Levi Armand and Martha Nell Smith. Unpublished manuscript. Martha Dickinson Bianchi papers, MS 2010.046. Special Collections, Brown University Library, Providence RI.

Bingham, Millicent Todd. Emily Dickinson’s Home. Harper and Brothers, 1955.

Brantley, Richard E. Experience and Faith: The Late-Romantic Imagination of Emily Dickinson. Palgrave, Macmillan, 2005.

Burbick, Joan. “‘One Unbroken Company’: Religion and Emily Dickinson.” New England Quarterly: A Historical Review of New England Life and Letters 53.1 (March 1980): 62-75.

Capps, Jack. Emily Dickinson’s Reading 1836-1886. Harvard UP, 1966.

Clark, Jr., Clifford Edward. The American Family Home, 1800-1960. U of North Carolina P, 1986.

Crumbley, Paul. “Dickinson’s Uses of Spiritualism: The ‘Nature’ of Democratic Belief.” A Companion to Emily Dickinson. Edited by Martha Nell Smith and Mary Loeffelholz. Blackwell, 2008. 235-257.

Dickinson, Emily. The Letters of Emily Dickinson. 3 vols. Edited by Thomas H. Johnson and Theodora Ward. Harvard UP, 1958

-----. The Poems of Emily Dickinson. 3 vols. Edited by R. W. Franklin. Harvard UP, 1998.

Dickinson, Susan Huntington. “Miss Emily Dickinson of Amherst.” The Springfield Republican. 18 May 1886. Reprinted in Open Me Carefully: Emily Dickinson’s Intimate Letters to Susan Huntington Dickinson. Edited by Martha Nell Smith and Ellen Louise Hart. Paris Press, 1998. 267-268.

Eberwein, Jane. “‘Is Immortality True?’ Salvaging Faith in an Age of Upheavals.” A Historical Guide to Emily Dickinson. Edited by Vivian R. Pollak. Oxford UP, 2004. 67-102.

Foster, John. Miscellaneous Essays on Christian Morals; Experimental and Practical. Originally Delivered as Lectures in the Broadmead Chapel, Bristol, England. Edited by J. E. Ryland. New York: D. Appleton & Co.; Philadelphia: George S. Appleton, 1844.

Freedman, Linda. Emily Dickinson and the Religious Imagination. Cambridge UP, 2011.

Gatta, John. “The Anglican Aspect of Harriet Beecher Stowe.” The New England Quarterly 73 (Sept. 2000): 412-433.

Gilliland, Don. “Textual Scruples and Dickinson’s ‘Uncertain Certainty’.” Emily Dickinson Journal 18.2 (2009): 38-62.

Goluboff, Benjamin. “‘If Madonna Be’: Emily Dickinson and Roman Catholicism.” The New England Quarterly 73 (Sept. 2000): 355-385.

“Guide to the Martha Dickinson Bianchi papers.” Rhode Island Archival and Manuscript Collections Online [RIAMCO]. 2010. https://library.brown.edu/riamco/xml2pdffiles/US-RPB-ms2010.046.pdf. Accessed 20 January 2020.

Habegger, Alfred. “A Glimpse at Emily Dickinson's Reading.” New England Review 22.4 (Fall 2001): 96-99.

-----. “My Wars are Laid Away in Books”: The Life of Emily Dickinson. Random House, 2001.

Heginbotham, Eleanor Elson. “Reading in the Dickinson Libraries.” Emily Dickinson in Context. Edited by Eliza Richards. Cambridge UP, 2013. 25-35.

-----. “What are you reading now? Emily Dickinson’s Epistolary Book Club.” Reading Emily Dickinson’s Letters: Critical Essays. Edited by Jane Donahue Eberwein and Cindy MacKenzie. U of Massachusetts P, 2009. 126-160.

Heininger, Mary Lynn Stevens. At Home with A Book: Reading in America, 1840-1940. Rochester NY: Strong Museum, 1986.

Hughes, Glenn. “Love, Terror, and Transcendence in Emily Dickinson's Poetry.” Renascence: Essays on Values in Literature 66.4 (Fall 2014): 283-304.

Huntington, Arria A. Memoir and Letters of Frederic Dan Huntington, First Bishop of Central New York. Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1906.

Huntington, F. D. Christian Believing and Living. Boston: Crosby, Nichols, and Company, 1860.

-----. Letter to Susan Huntington Dickinson. [n.d.] Susan Huntington Dickinson correspondence. Dickinson family papers, MS Am 1118.95. Houghton Library, Harvard University, Cambridge MA.

-----. Letter to Susan Huntington Dickinson. 14 September 1898. Martha Dickinson Bianchi papers, MS 2010.046. Special Collections, Brown University Library, Providence RI.

Keane, Patrick J. Emily Dickinson's Approving God: Divine Design and the Problem of Suffering. U of Missouri P, 2008.

Kempis, Thomas à. Of the Imitation of Christ: Four Books, Oxford, London: John Henry and James Parker, 1857.

Kruger, Linda M. “Home Libraries: Special Spaces, Reading Places.” American Home Life, 1880-1930: A Social History of Spaces and Services. Edited by Jessica H. Foy and Thomas J. Schlereth. U of Tennessee P, 1992. 94-119.

LeMay, Kristin. “I told my soul to sing”: Finding God with Emily Dickinson. Paraclete Press, 2012.

Leyda, Jay. The Years and Hours of Emily Dickinson. 2 vols. Yale UP, 1960.

Longsworth, Polly. Austin and Mabel. U of Massachusetts P, 1984.

Lundin, Roger. Emily Dickinson and the Art of Belief. Second ed. Wm. B. Eerdmans, 2004.

Lowenberg, Carlton. Emily Dickinson’s Textbooks. Lafayette CA: Carlton Lowenberg, 1986.

McIntosh, James. Nimble Believing: Dickinson and the Unknown. U of Michigan P, 2000.

Maxon, W. D. “Frederic Dan Huntington [obituary].” The Church Eclectic. A Monthly Magazine 34.6 (September 1904): 481.

Mayer, Nancy. “The Back Story”: Christian Narrative and Modernism in Emily Dickinson’s Poems.” Emily Dickinson Journal 17.2 (2008): 1-23, 124-125.

-----. “God’s Place in Dickinson’s Ecology.” A Companion to Emily Dickinson. Edited by Martha Nell Smith and Mary Loeffelholz. Blackwell, 2008. 269-277.

Morgan, Victoria N. Emily Dickinson and Hymn Culture: Tradition and Experience. Ashgate, 2010.

Nylander, Jane C. Our Own Snug Fireside: Images of the New England Home, 1760-1860. Knopf, 1993.

Sewall, Richard B. The Life of Emily Dickinson. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1974.

-----. The Lyman Letters: New Light on Emily Dickinson and Her Family. U of Massachusetts P, 1965.

Stonum, Gary Lee. “Dickinson’s Literary Background.” The Emily Dickinson Handbook. Edited by Gudrun Grabher, Cristanne Miller, and Roland Hagenbuchle. U of Massachusetts P, 1998. 44-60.