Click here for supplemental notes and commentary.

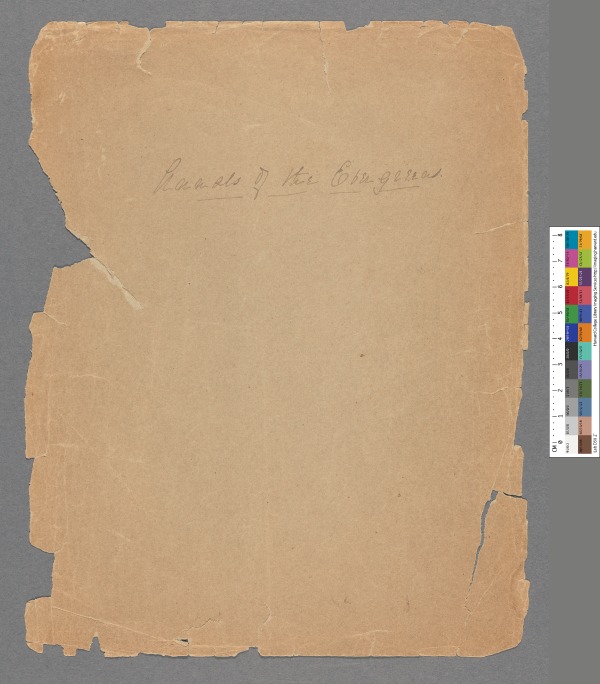

< cover page recto, verso >

< frontpiece recto, verso >

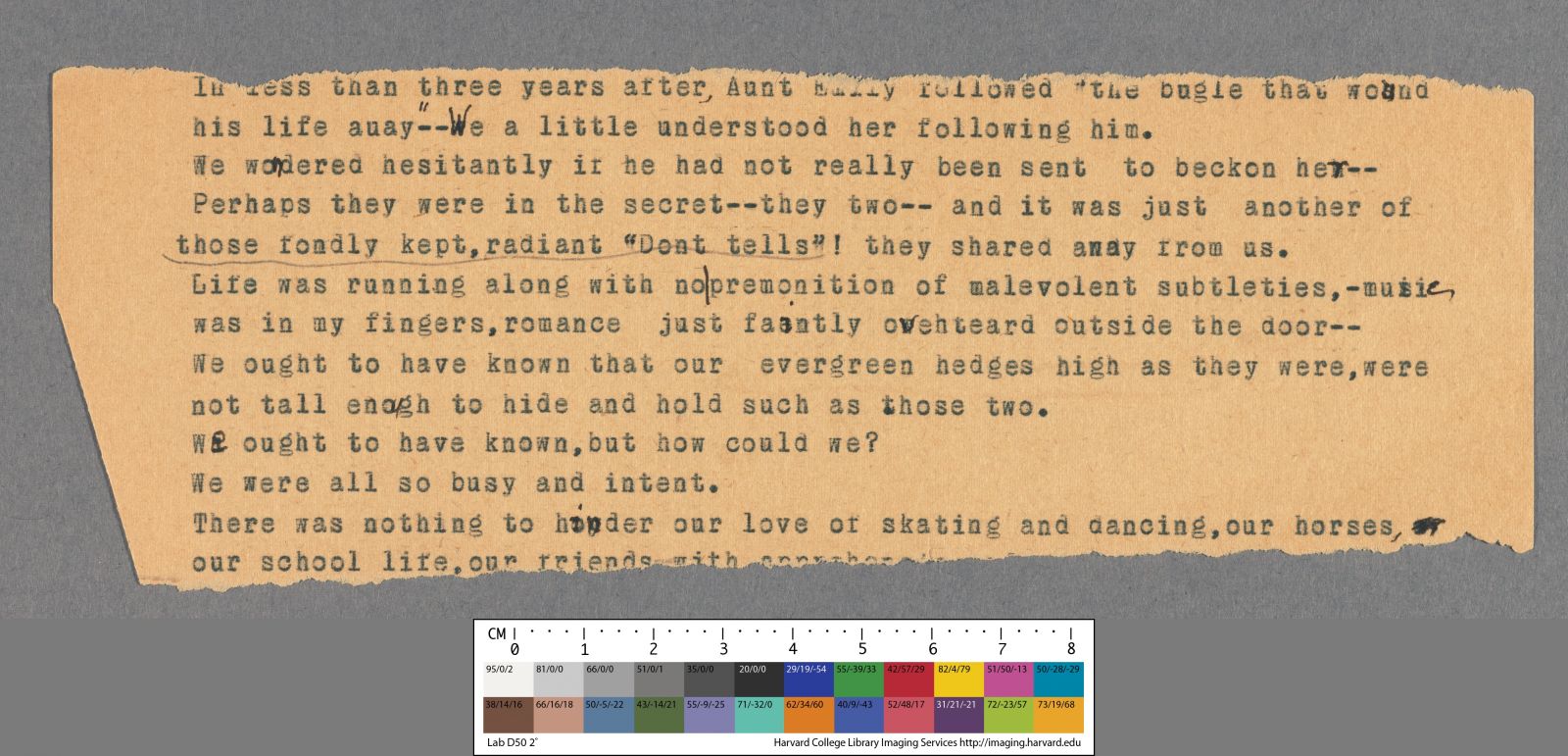

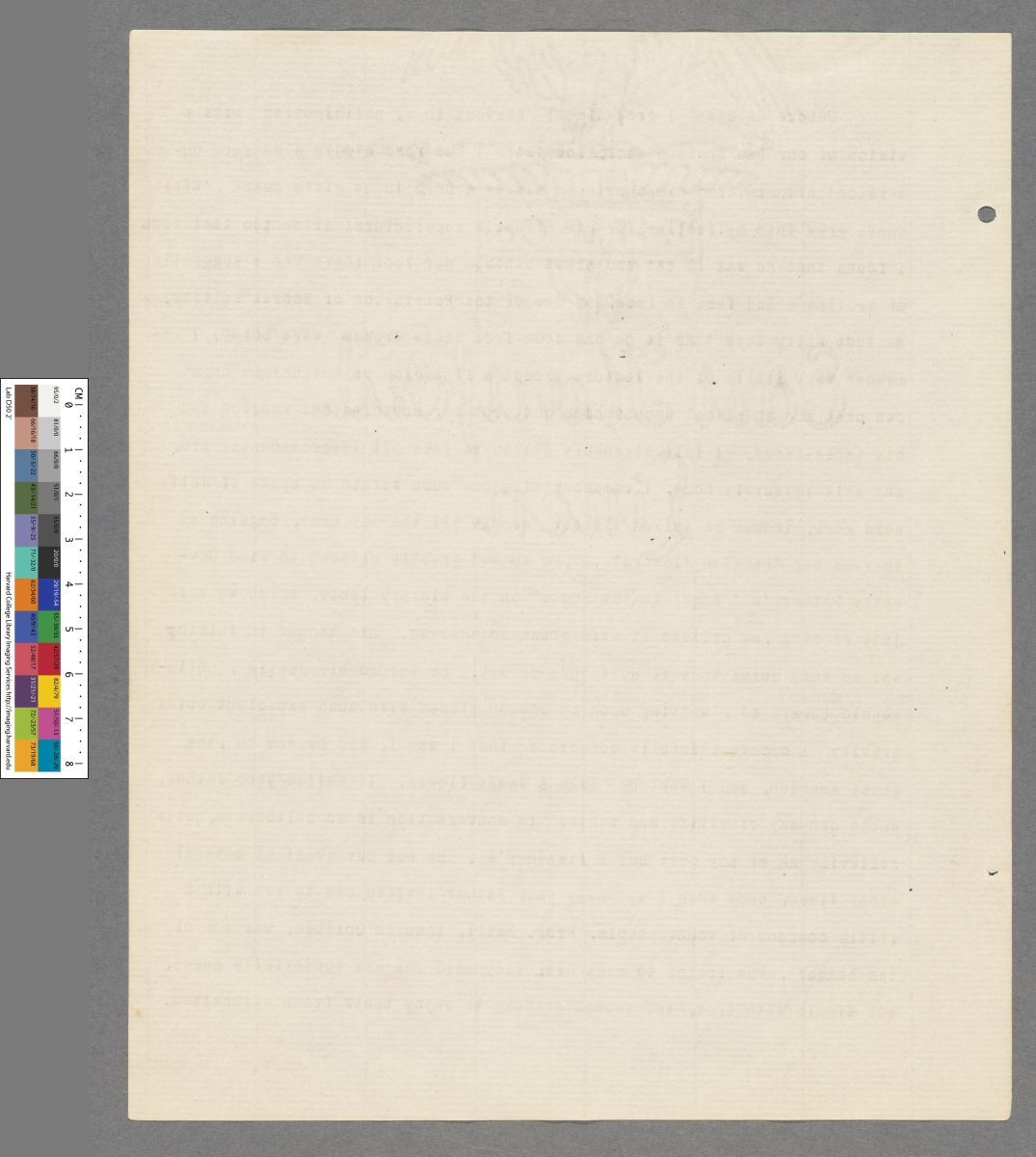

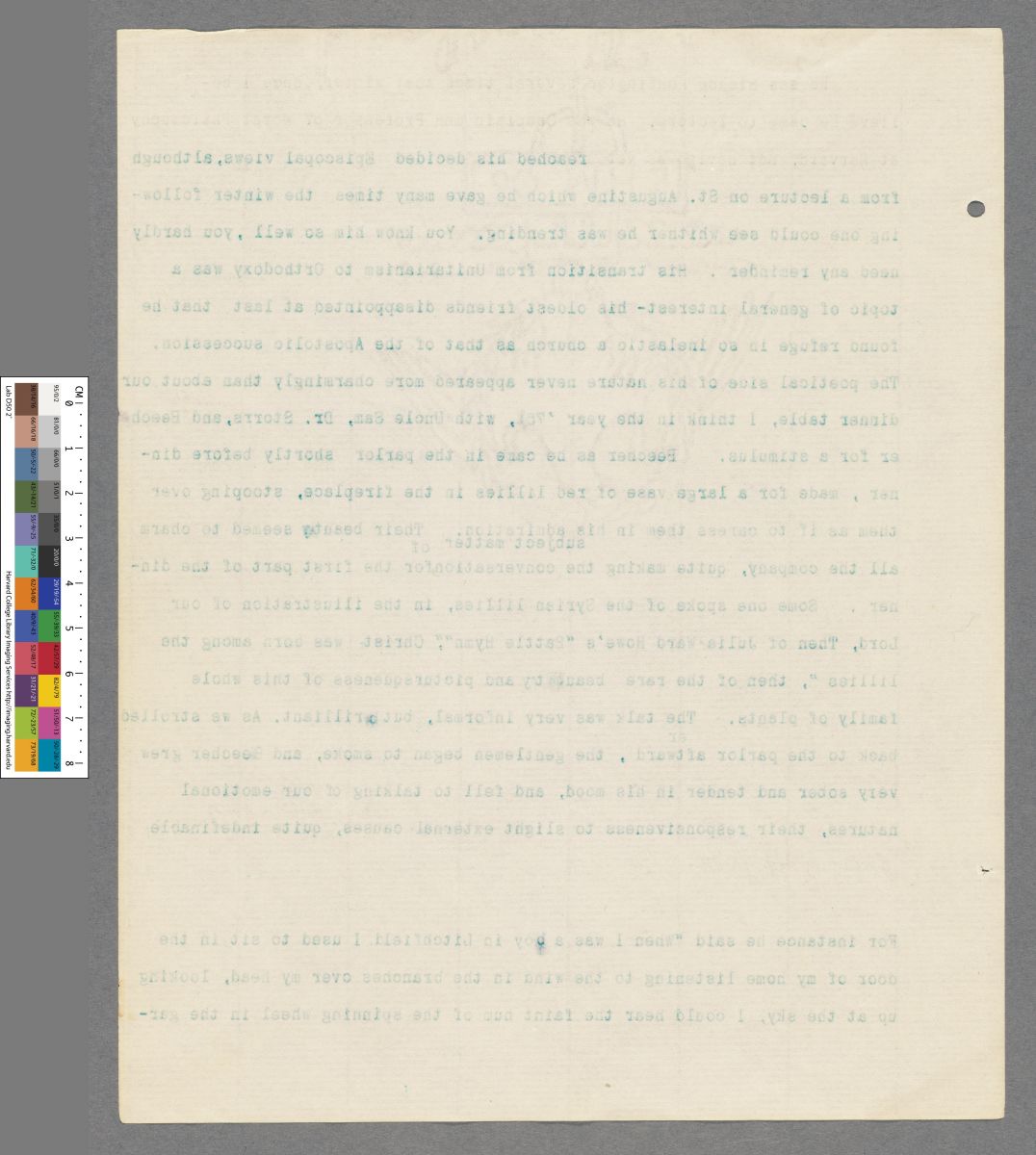

< transcription 1 recto, verso >

< transcription 2 recto, verso >

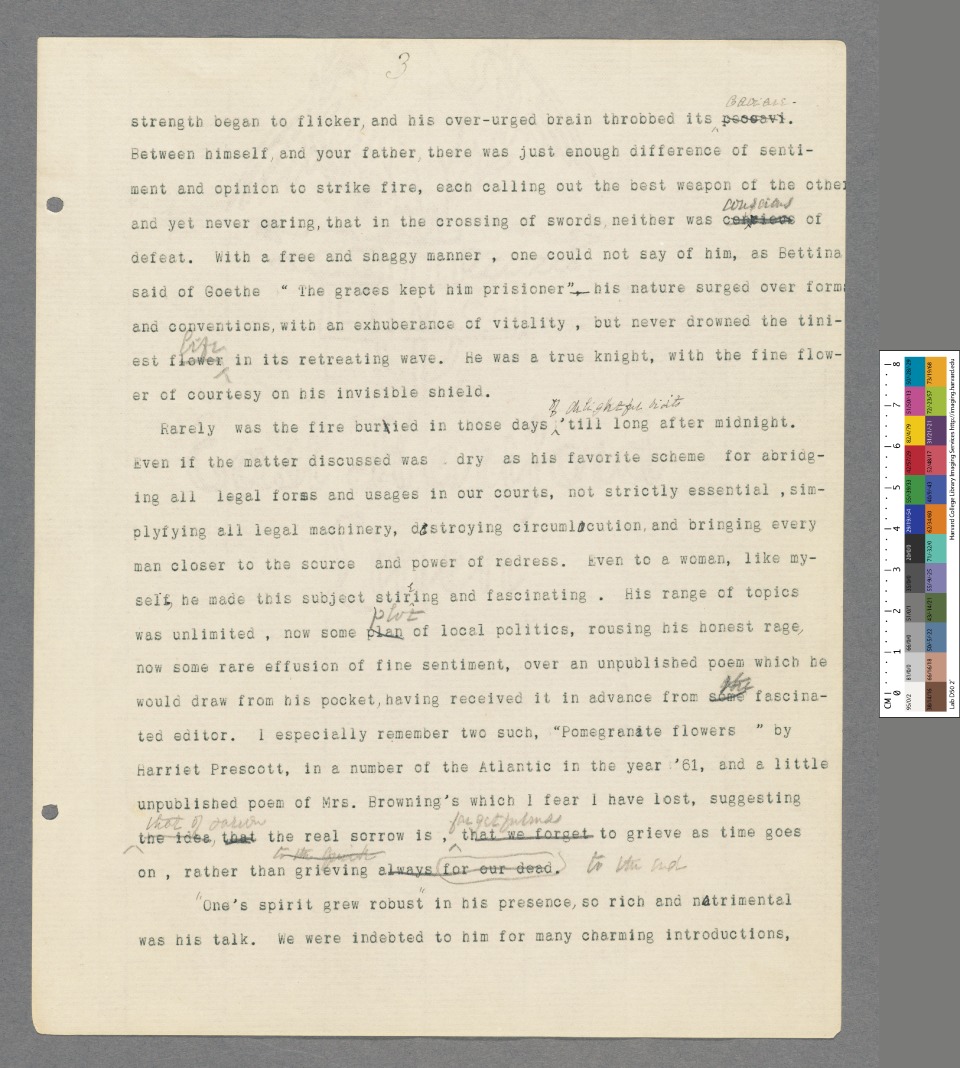

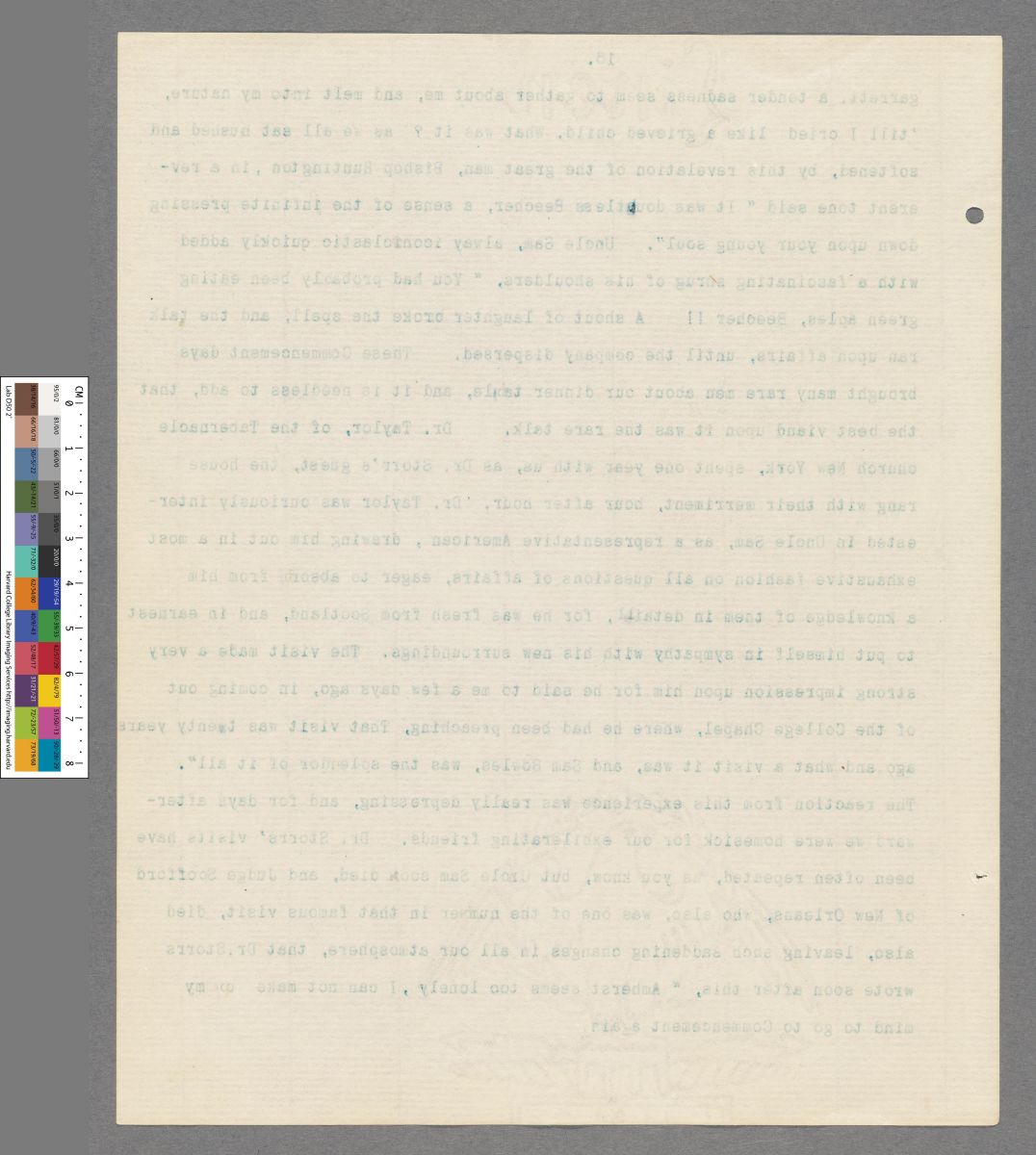

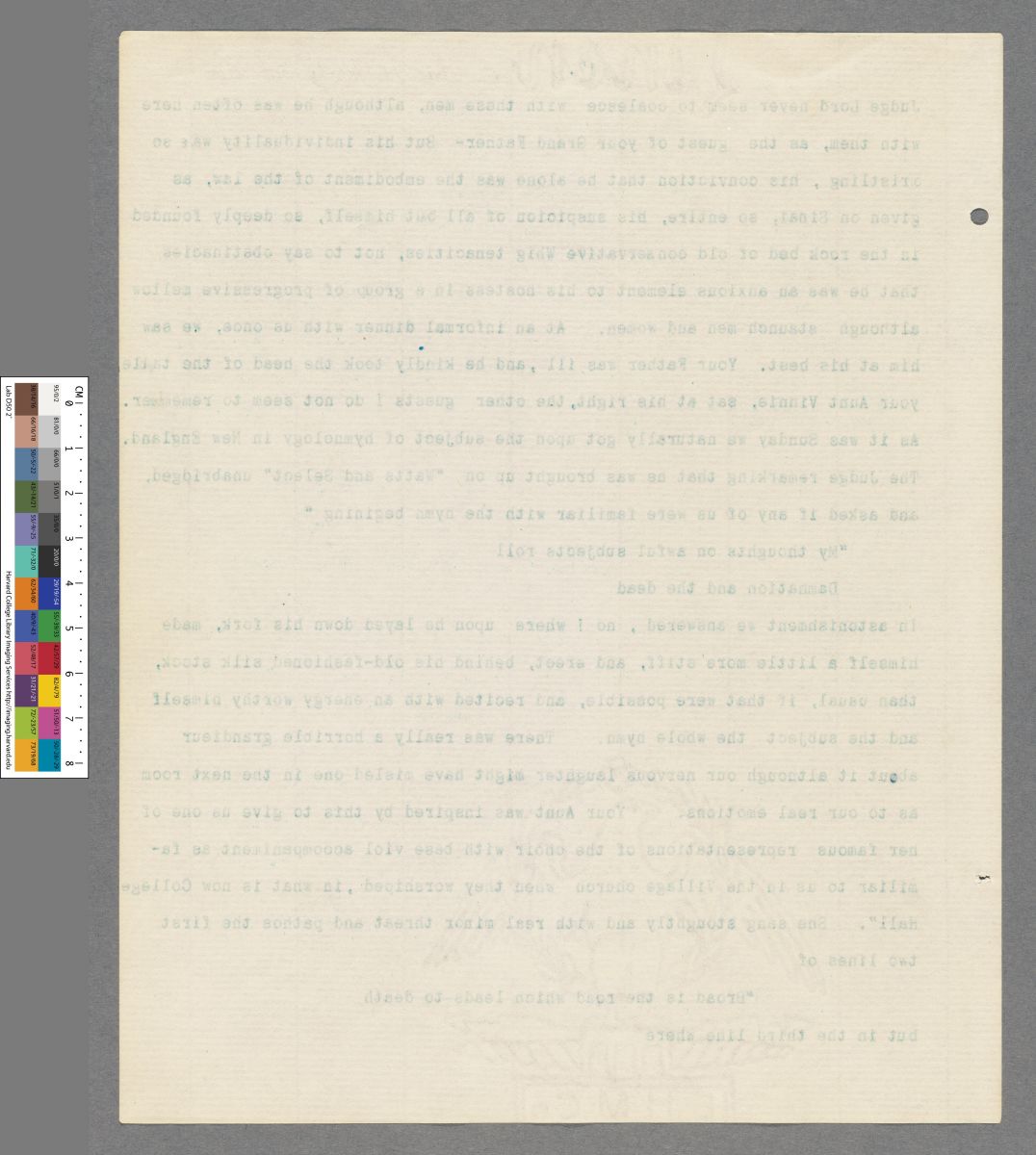

< transcription 3 recto, verso >

< transcription 4 recto, verso >

< transcription 5 recto, verso >

< transcription 6 recto, verso >

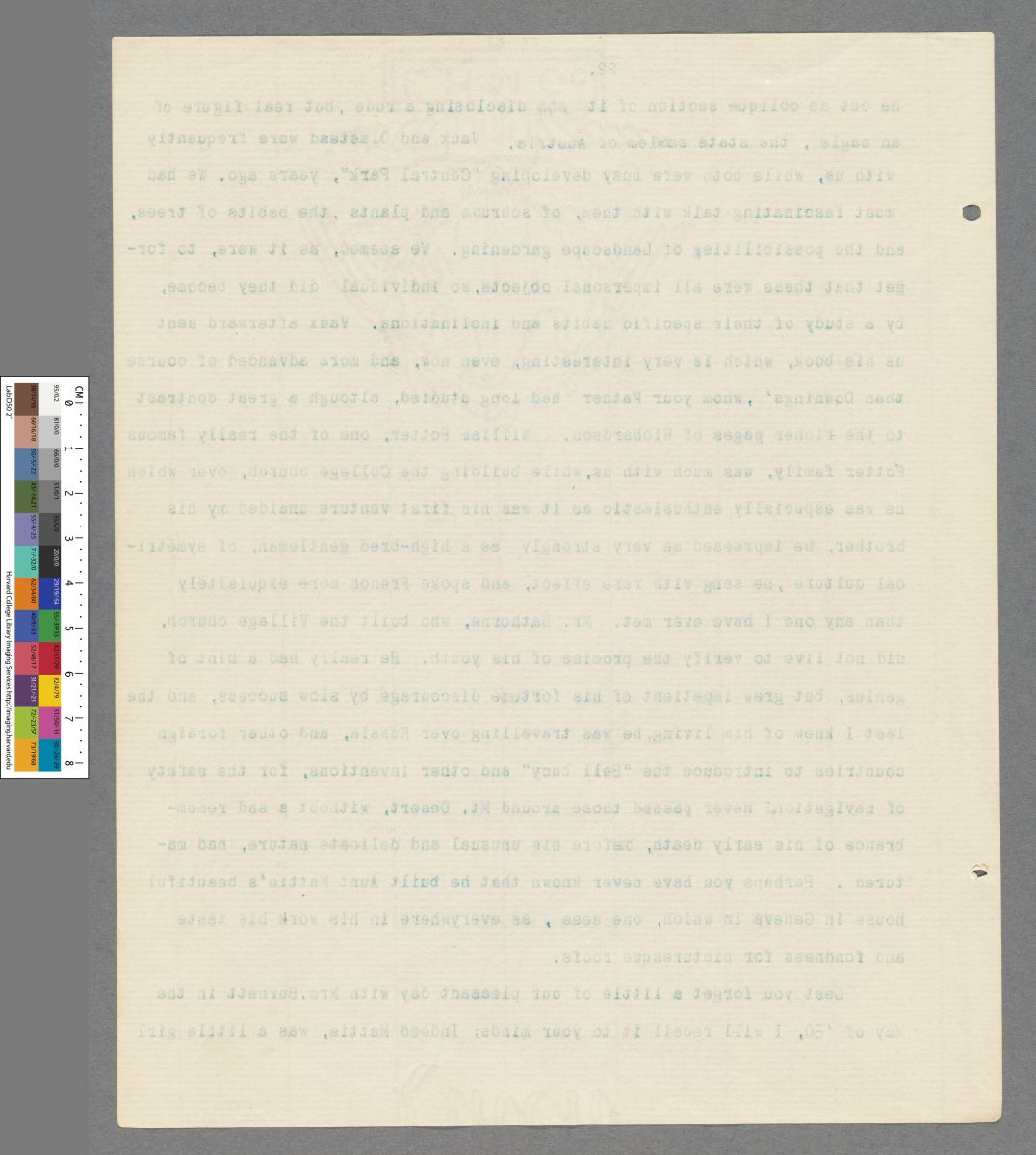

< transcription 7 recto, verso >

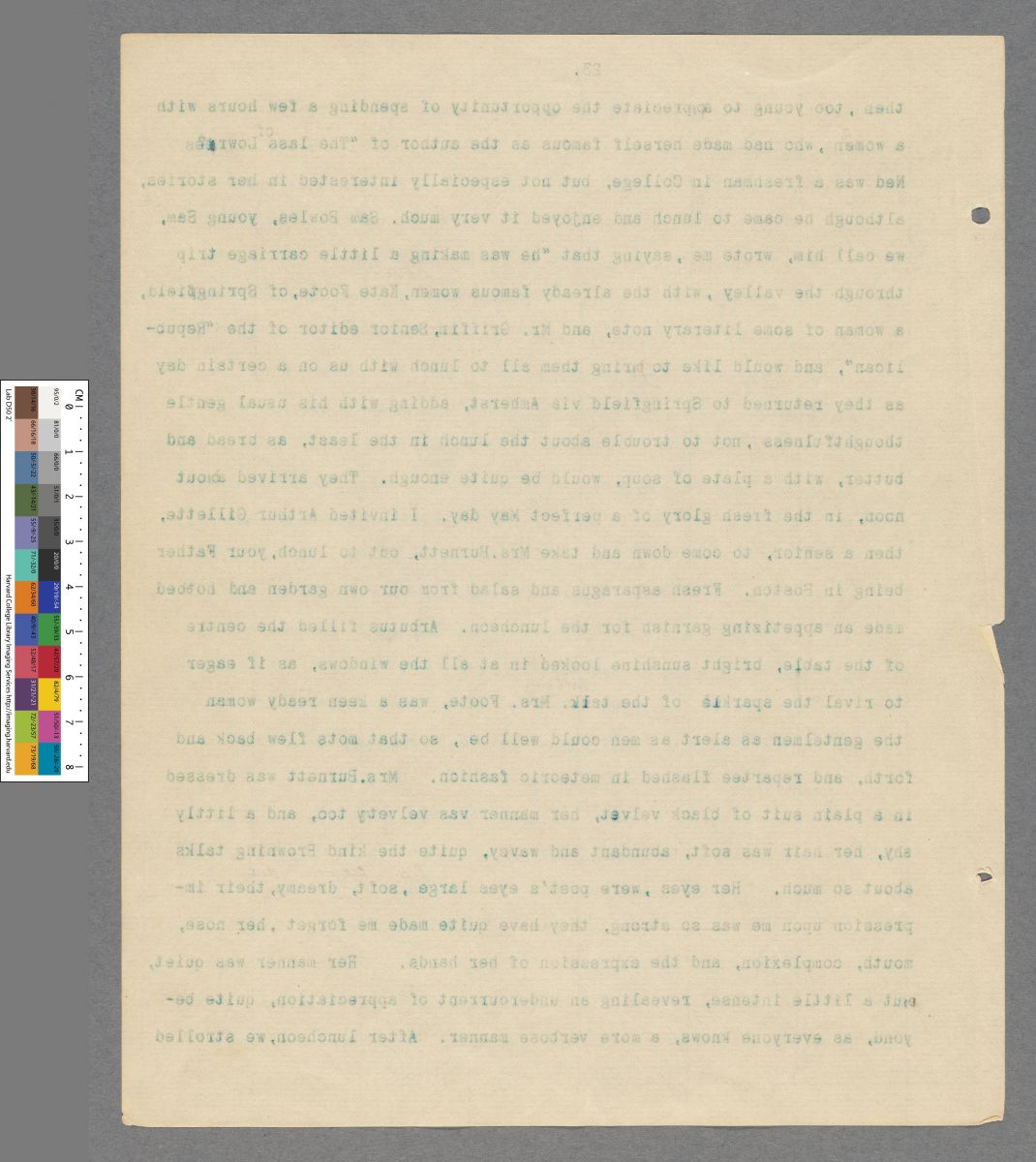

< transcription 8 recto, verso >

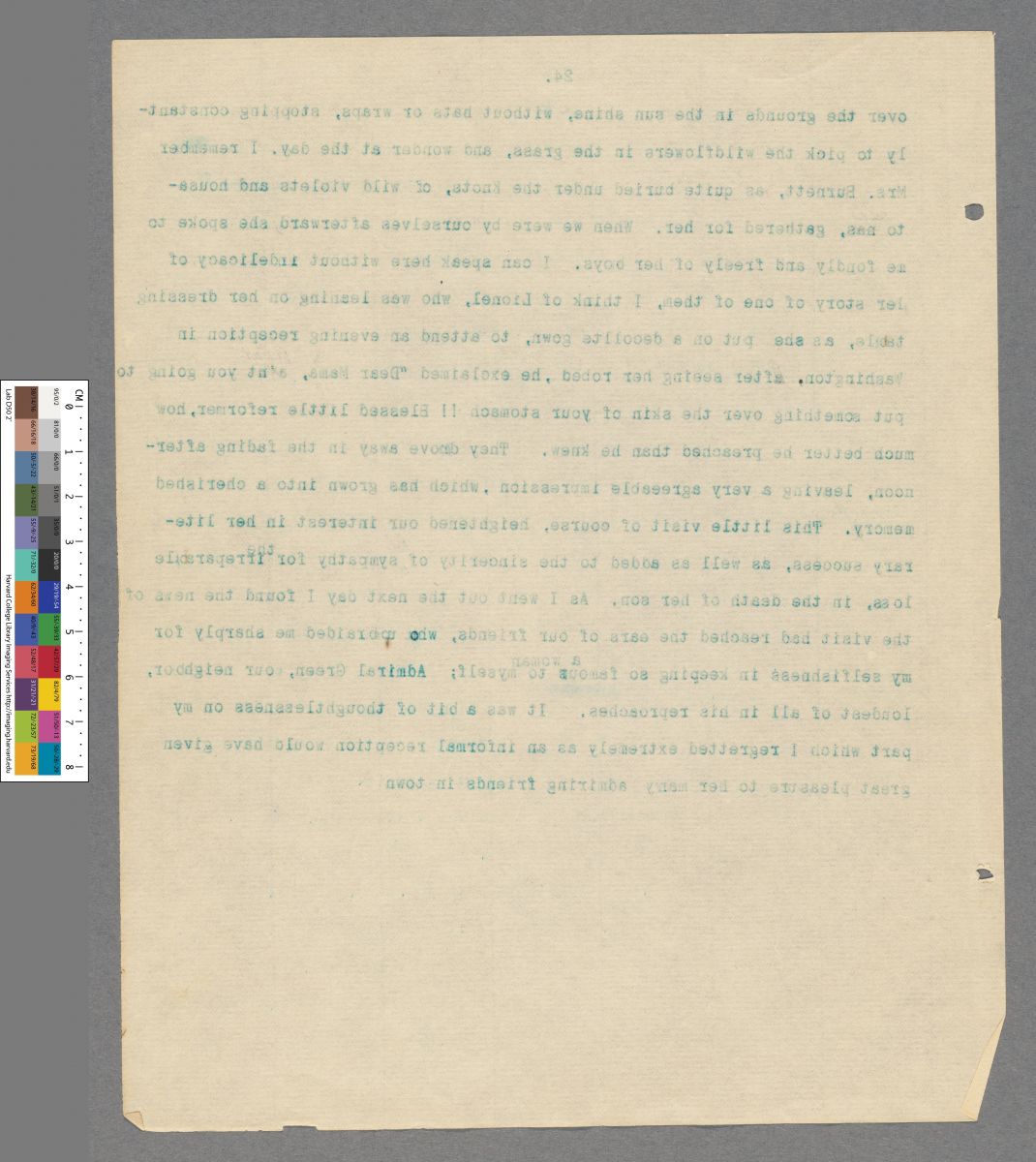

< transcription 9 recto, verso >

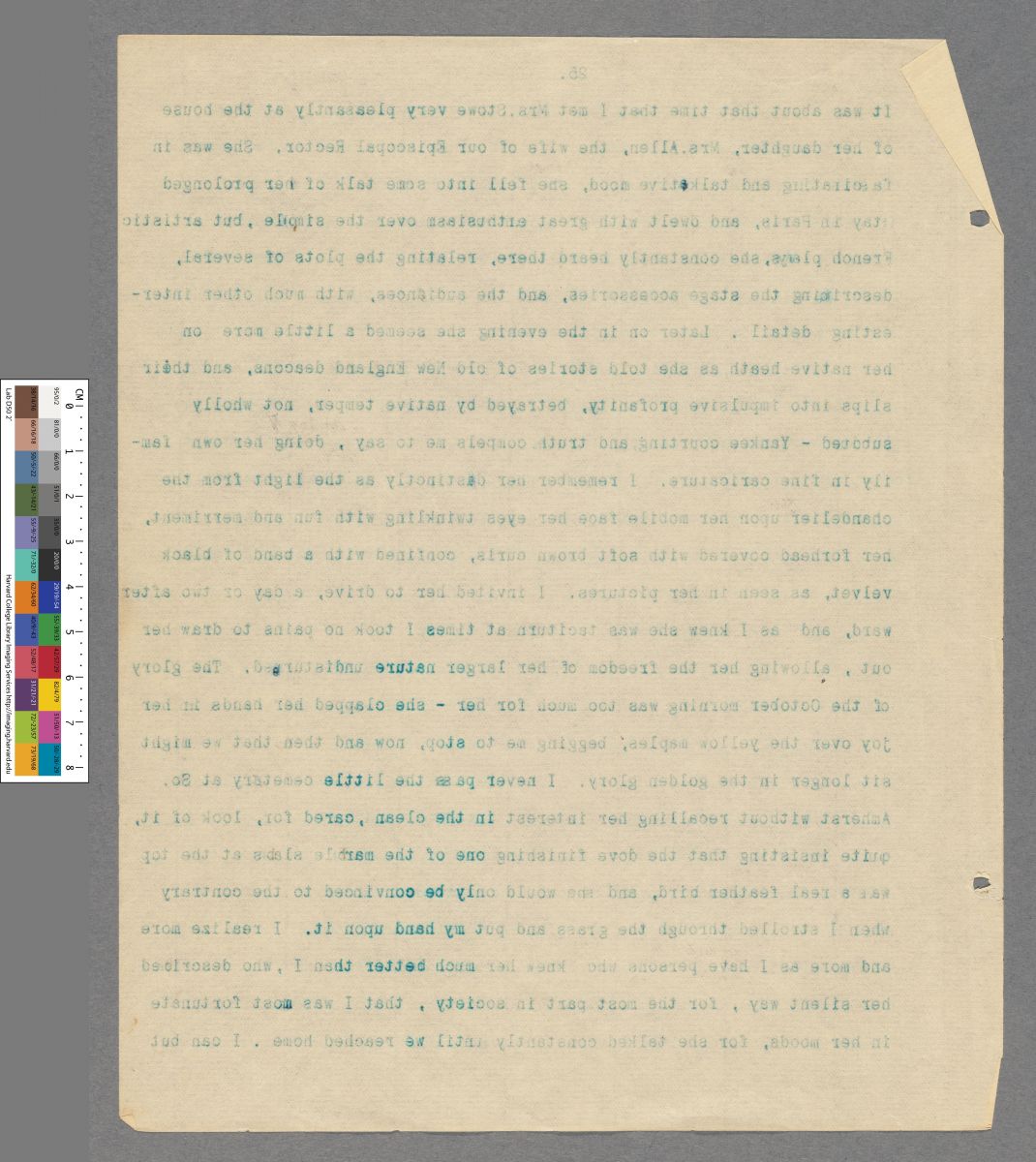

< transcription 10 recto, verso >

< transcription 11 recto, verso >

< transcription 12 recto, verso >

< transcription 13 recto, verso >

< transcription 14 recto, verso >

< transcription 15 recto, verso >

< transcription 16 recto, verso >

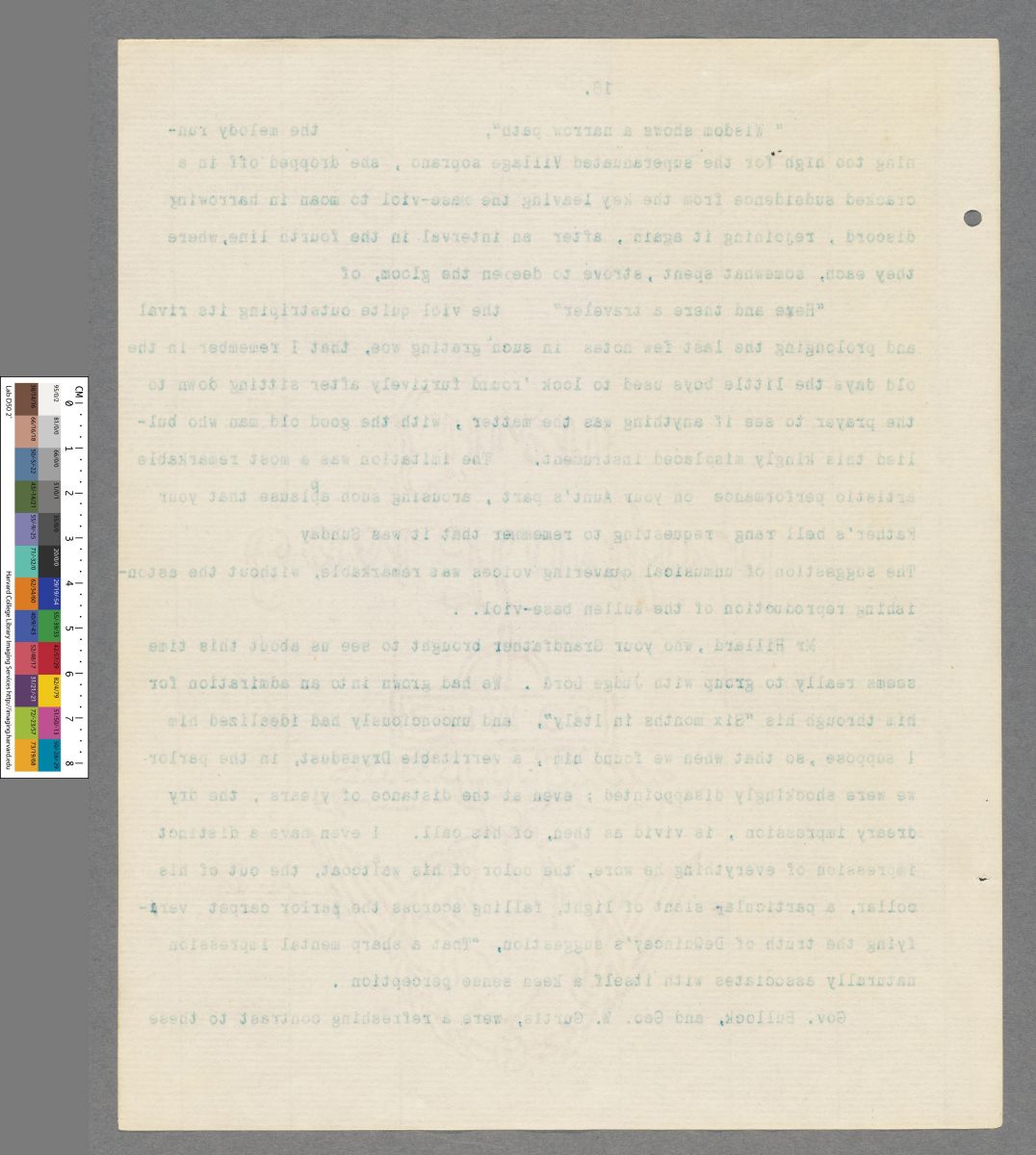

< transcription 17 recto, verso >

< transcription 18 recto, verso >

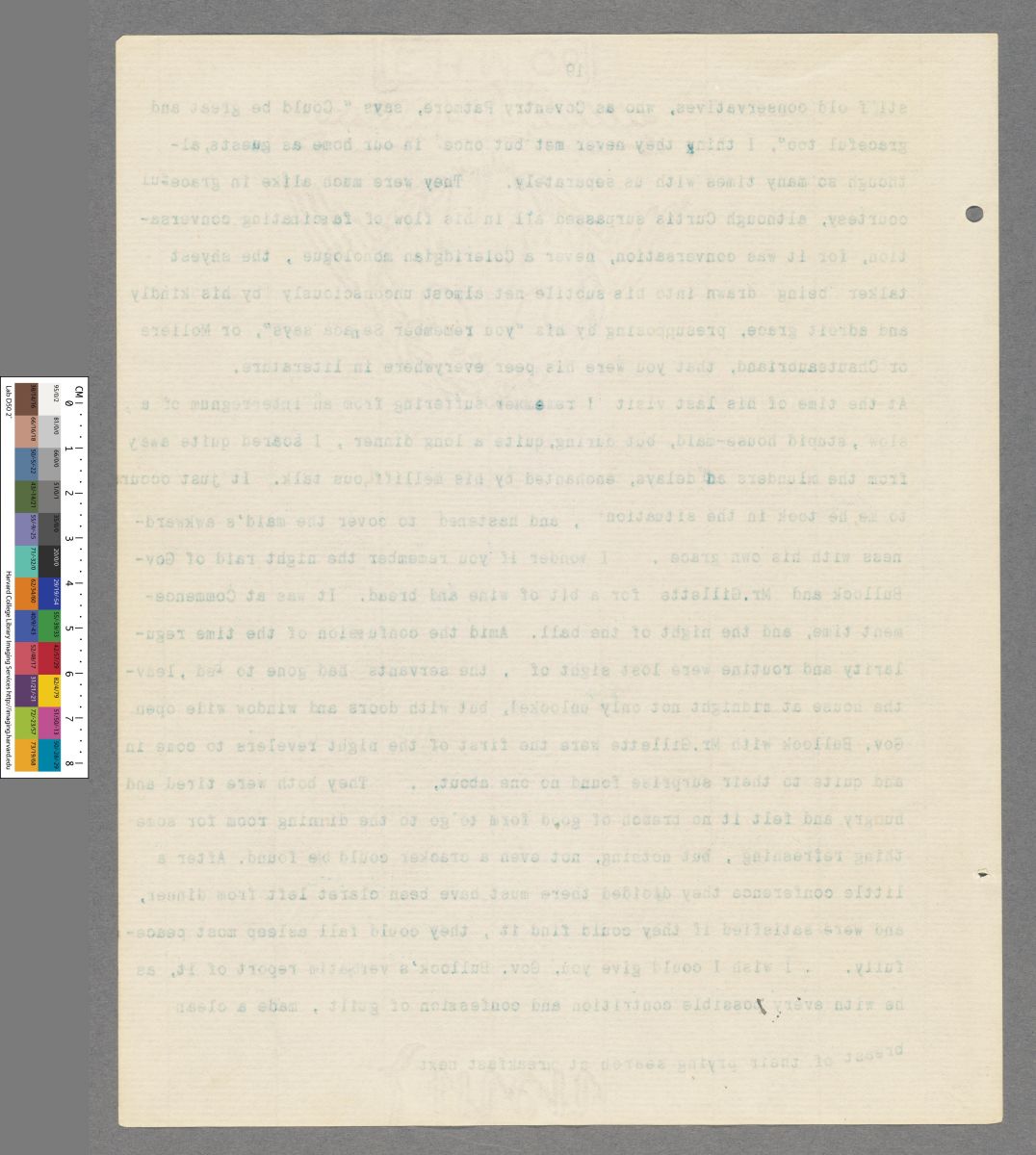

< transcription 19 recto, verso >

< transcription 20 recto, verso >

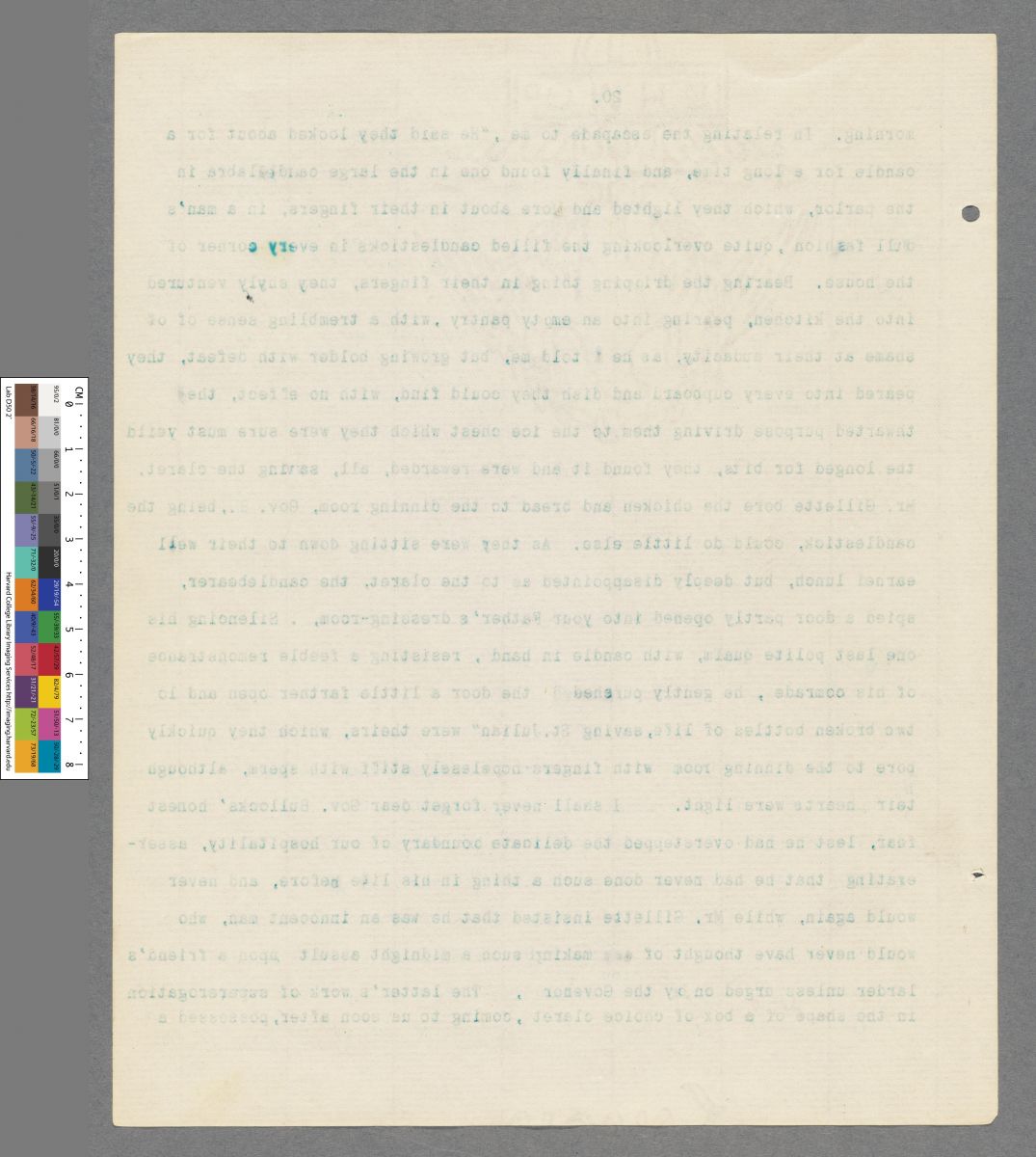

< transcription 21 recto, verso >

< transcription 22 recto, verso >

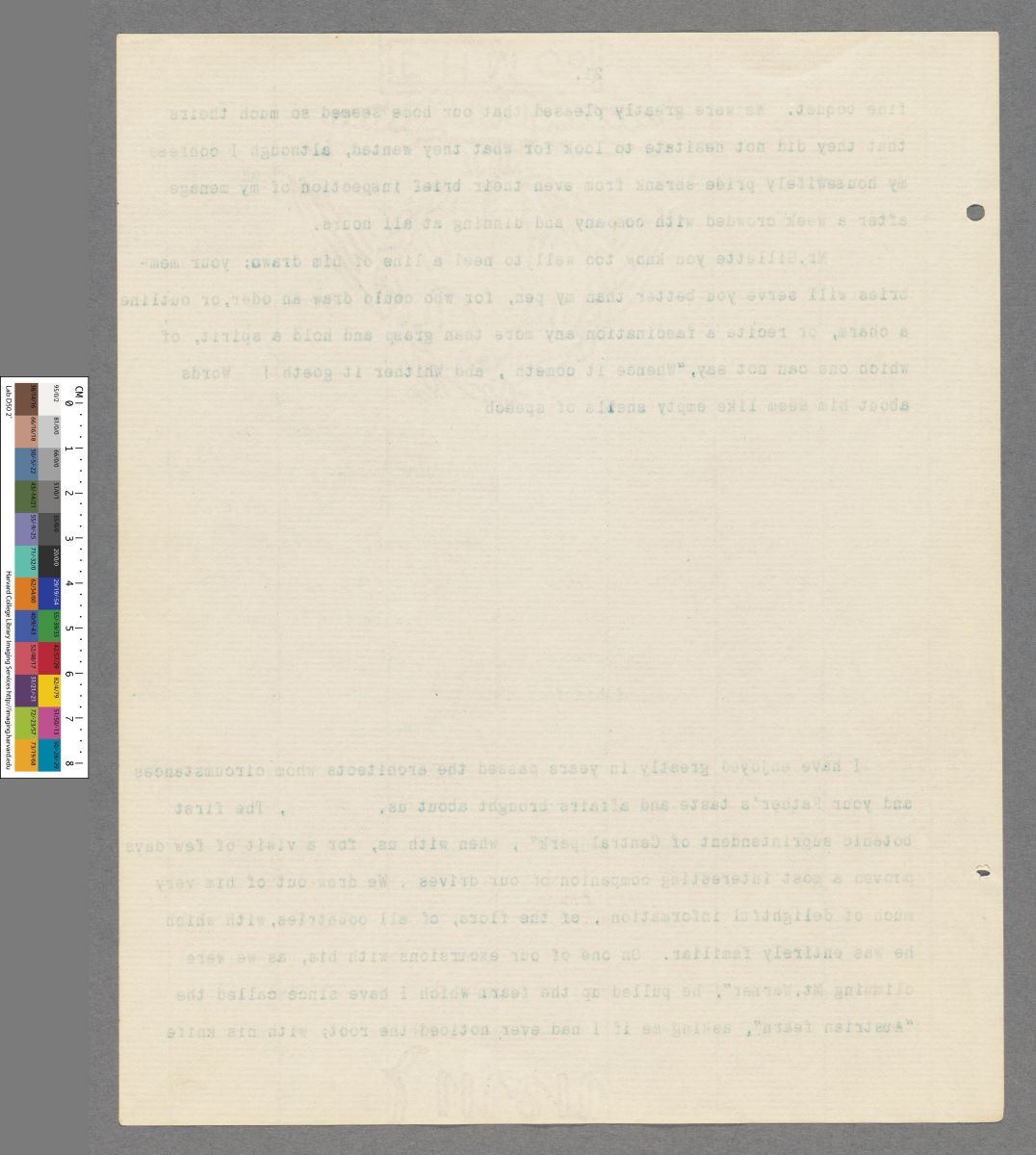

< transcription 23 recto, verso >

< transcription 24 recto, verso >

< transcription 25 recto, verso >

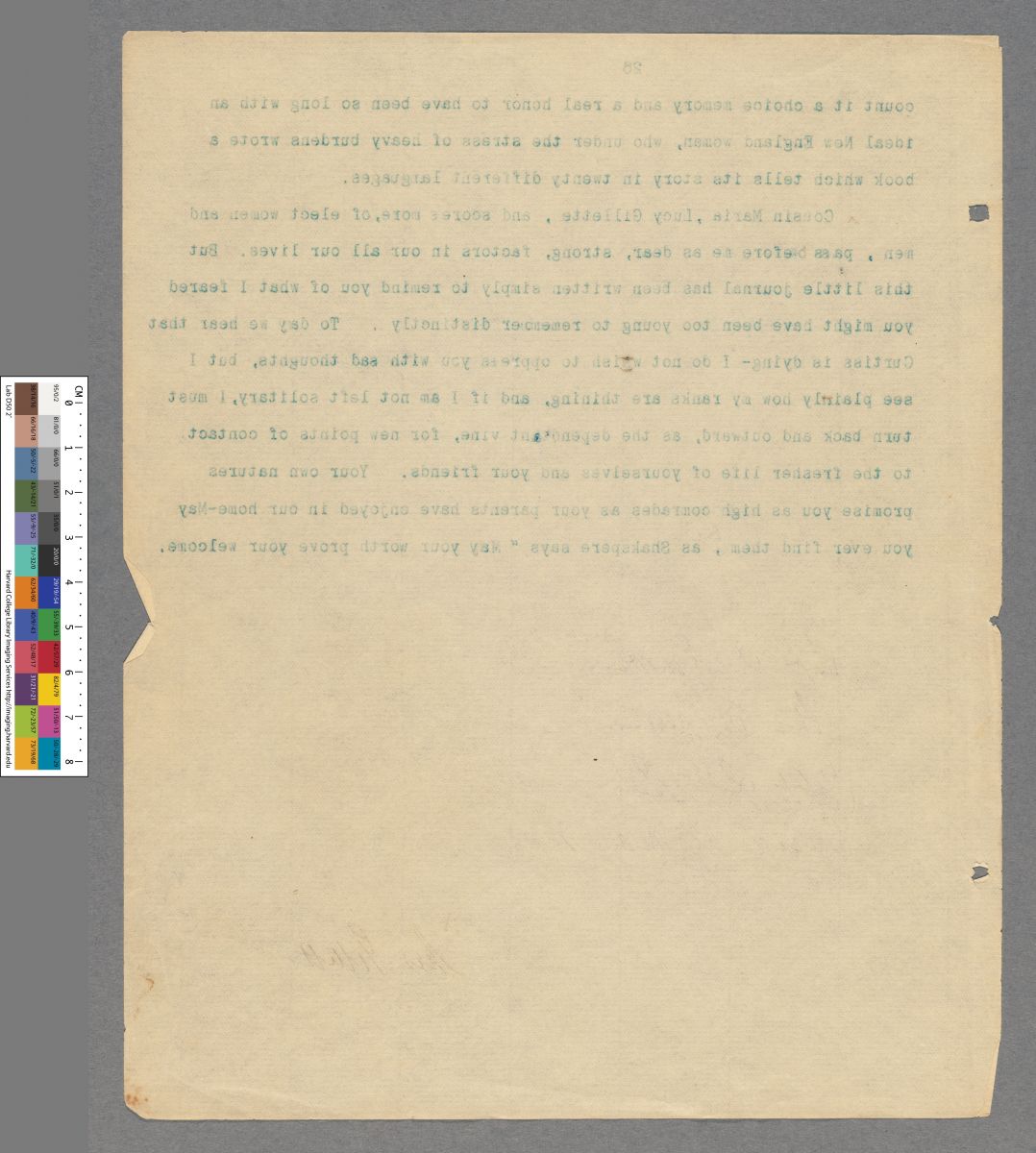

< transcription 26 recto, verso >

H bMS Am 1118.95, Box 9

Supplementary Notes and Commentary

Annals of the Evergreens

Written and prepared for typescript in 1892, Susan Dickinson's Annals of the Evergreens provides an important record of the active social and intellectual life of the Dickinson family between 1856 and 1880. As a result of a long-standing affiliation with Amherst College (the elder Mr. Dickinson held the position of treasurer from 1835 to 1873 when his only son Austin assumed the office) and the family's prominent role in the town's social and political circles, the Dickinsons hosted some of the most influential figures in nineteenth century American Politics, Arts and Letters, many of whom became close friends. Among others, Annals recounts the visits of Ralph Waldo Emerson, Harriet Beecher Stowe, abolitionist Wendell Phillips, and landscape designer Frederick Olmsted.

Due to the proximity of the Homestead (only 200 yards away) and the close relationship between the two houses, it is likely that Emily and Lavinia Dickinson made the acquaintance of certain honored guests. As an avid reader, writer and intellectual force in the family, Emily's own philosophies and aesthetic sensibilities certainly contributed to the rich exchange of ideas alluded to throughout the memoir and, we can assume, helped shape her own work to some degree. Emerson, in particular, earned the respect and awe of the Dickinsons long before his visit. In describing the great anticipation with which he was received, Susan writes "there was a suggestion of meeting God face to face... or as 'Aunt Emily' says, 'As if he had come from where dreams are born."

In the opening paragraphs of Annals, Susan declares her own gratitude for these associations and places above "any material good... the personal influences which have stimulated and delighted me, my relations with rare people who have given me their best wealth and sympathy, sometimes a life of devoted friendship" (1).

Though Annals of the Evergreens figures prominently as critical witness to the Dickinson "scene of literary production," the manuscript also distinguishes itself in other important, and related, ways. Through a close and critical reading of Susan's narrative, its development and consciousness, Annals allows us to recover and study revealing articulations of self, of gender and genre, class and race in nineteenth-century New England.

Frontispiece

Most likely written after Susan Dickinson's death in 1913, this frontispiece is prepared by her daughter Martha Dickinson Bianchi. Bianchi may have considered publishing Annals in is entirety at one time and does excerpt and include portions of it in a biographical account of her Aunt's life, Emily Dickinson Face to Face (1932). In that context, Bianchi uses "Annals" to paint a portrait of the lively, intellectual and "Beloved Household" that was The Evergreens:

"To look that way is romance," Emily wrote to Sue... And long after she had ceased to go elsewhere beyond her own dooryard, Emily still slipped across the little path to spend happy evenings there (124).

Included in Bianchi's Face to Face are Susan's description of Emerson, her catalogue of honored guests, and Susan's tender memorial of Samuel Bowles, founding editor of the Springfield Republican and cherished friend.

By contrast with Face to Face, Bianchi's preface to Annals focuses narrowly on Susan's acquaintance with Frances Hodgson Burnett, Harriet Beecher Stowe and her own part in that particular meeting. Though Burnett is best known today for her famous children's stories (Little Lord Fauntleroy, The Secret Garden and The Little Princess), Susan and Martha would have been equally as familiar with her earlier realistic novels, in which Burnett takes up issues of class and gender in particular. This focused grouping of women seems to suggest that, at the very least, Bianchi made connections between her Mother's ideals and writings, her own writing and that of the prominent and socially conscious Burnett and Stowe. Though there is no known evidence that Bianchi publishes Annals in its entirety, she seems to have imagined an audience sympathetic to women's issues and perhaps even saw the manuscript published in this context. In any case, an editorial note such as this would have been necessary in assigning her mother's various writings their particular significance.

Though brief, Bianchi's synopsis is careful to reiterate Susan's authorship and to echo her Mother's declared purpose in writing "for her children." This gesture both anticipates a public audience (whether for Bianchi or her Aunt or both-- it is not clear) and preserves her mother's reputation as a "True Woman" devoted to her family and disinclined towards public life and recognition. It is important to note that this sort of double rhetoric would have been commonplace within the middle to late nineteenth-century consciousness and code of genteel womanhood (Tonkovich 49).

Though Susan shared to some extent Emily's skepticism of print, as a more conventional writer Susan would not have felt as keenly the disappointment of misrepresentation (see Emily's letter to Higginson, L 316, early 1866). An avid reader and writer, Susan prints numerous stories, reviews, essays and eulogies throughout her adult life, some of which were anonymous and others accompanied only by her initials. Thus, Susan's humility and sense of propriety should not distract contemporary readers from the author's careful and conscious writerly attentions, her critical, historical, autobiographical and biographical reflections.

Page 1

Susan's epigraphs are the foundation of Annals' theme, and part of a larger nineteenth-century preoccupation with heroes and hero-worship, of which she makes explicit mention here (Goldberg xxxiii). Both quotes are taken from the first of Sir Thomas Carlyle's famous 1840 lectures on the subject: "Heroes, Hero-Worship, & the Heroic in History". The particular lecture from which she quotes, "The Hero as Divinity. Odin. Paganism: Scandinavian Mythology," offers significant insight into Susan's philosophy in preparing Annals. In this essay and others, Carlyle sets out to define what he calls "Great Men" and by this defines his thesis, which Susan herself seems to take up, that "the soul of the whole world's history, it may justly be considered, were the history of these" (3).

Carlyle goes on to examine the relationship of his "Great Men" to the Divine, and it is from this context that Susan takes the St. Chrysostom quote, as well as her allusion to the "Divine Spirit" which "whispers in [the children's] ears":

But now if all things whatsoever that we look upon are emblems to us of the Highest God, I add that more so than any of them is man such an emblem. You have heard of St. Chrysostom's celebrated saying in reference to the Shekinah, or Ark of Testimony, visible Revelation of God, among the Hebrews: "The true Shekinah is Man!"... The essence of our being, the mystery in us that calls itself "I,"--ah, what words have we for such things?--is a breath of Heaven; the Highest Being reveals himself in man. This body, these faculties, this life of ours, is it not all as a vesture for that Unnamed? (10).

It may be of particular interest that Susan takes her epigraph and theme from an essay in which the self or "I" and its physical body are defined (and celebrated) as "a breath of heaven" and "vesture for that Unnamed," respectively. Taking into account Susan's own socio-historical moment, such an equation may have presented her with an acceptable and honorable narrative frame for her personal reflections. In appreciating the need for such a "permission," it is helpful to remember that throughout most of Susan's lifetime, public life aroused suspicion and, as a rule, "public anonymity was the mark of God-given femininity" (Davidson 85); as a result, comparatively few writings by American women appeared in print, and of those that did, even fewer used their real names or wrote from a personal perspective. Autobiography by women does not become a widely-published, widely-circulated genre until the early twentieth century. There are some notable exceptions, however -- most of which were published around the same time Susan composed Annals. Susan was likely familiar with and perhaps influenced by works such as Lydia Sigourney's Letters of Life (1866), Lucy Larcom's A New England Girlhood: Outlined from Memory (1889),and Julia Ward Howe's Reminiscences 1819-1899 (1899). Though all these authors were active publically, their autobiographical narratives still take shape within the confines of socially acceptable bourgeois femininity, in which each autobiographical subject must "constitute femininity as well as republican subjectivity and to construct it in such a fashion as to legitimize the claim to narrative authority" (86). Thus, like many of her more radical compatriots, it is natural that Susan would, in preparing a personal narrative for typescript, avoid the labels of "autobiography" or "memoir" and emphasize instead her genuine (and more orthodox) devotion to her children.

Page 3

In quoting "Bettina," Susan refers to author Bettina von Arnim (1785-1859), who began her literary career at age 46 by publishing her correspondance with the famous German poet and philosopher Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. Von Armin was also known for her political activism and used her writing to lobby for social reform. We can assume that Susan, who deeply admired the writings of Goethe, takes the quotation from her own copy of von Armin's Correspondance With a Child.

Susan's description of Bowles as a "true knight" is part of a larger medievalist impulse in nineteenth-century America. Susan's use of it here echoes the condolance correspondance following Ned's death, in which certain friends refer to Ned as a "perfect knight."

For notes on Susan's self-deprication, e.g., "Even to a woman, like myself" and the anxiety of authorship see note, page 1.

According to Annals, Bowles often received poems and stories in advance of their publication elsewhere, and, in the course of their friendship, shared a number of these with the Dickinsons. Susan mentions two authors in particular. Harriet Prescott [Spofford] (1835-1921) earned early recognition for her story "In a Cellar" (Atlantic Monthly, 1859). Spofford was not only a short-story writer and poet but also a novelist and essayist whose writings numbered in the hundreds. Upon reading one of her stories, Emily writes to Susan, "That is the only thing I ever saw in my life I did not think I could have written myself. You stand nearer the world than I do. Send me everything she writes." Susan quotes Emily in her own review of Prescott's early work, published by the Springfield Republican in 1903.

Susan also refers to an unpublished poem by Elizabeth Barrett Browning (1806-1861) given to her by Bowles. Both Susan and Emily deeply admired the poet and frequently alluded to her and other favorite writers in their correspondance (xvii Hart, Smith). Moved by Barret Browning's death in June of 1861, Emily writes a tribute in the form of a poem (see "I think I was enchanted..." JP 593).

In the last paragraph of this page, Susan has added quotations to the typescript. She is quoting one of Emily's late poems (JP 1587), and may have had deeper knowledge of its context than has survived. If so, it is quite possible the poem is a memorial or tribute to Bowles, a dear and close friend.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)